Architectures of Science

The Universities of Berlin

in European Perspective

1 Where it all began: University in foreign dwellings

1 In Foreign Dwellings

The University of Berlin was founded in 1809, and from 1810 onwards courses were held. From 1828-1945 under the name “Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität”, since 1949 “Humboldt-Universität”, it formed the starting point for the university network in Berlin which is so rich today.

In its beginnings, however, it did not find its home in a special building for teaching and research, but was housed in a late baroque palace that was part of a historical architectural ensemble.

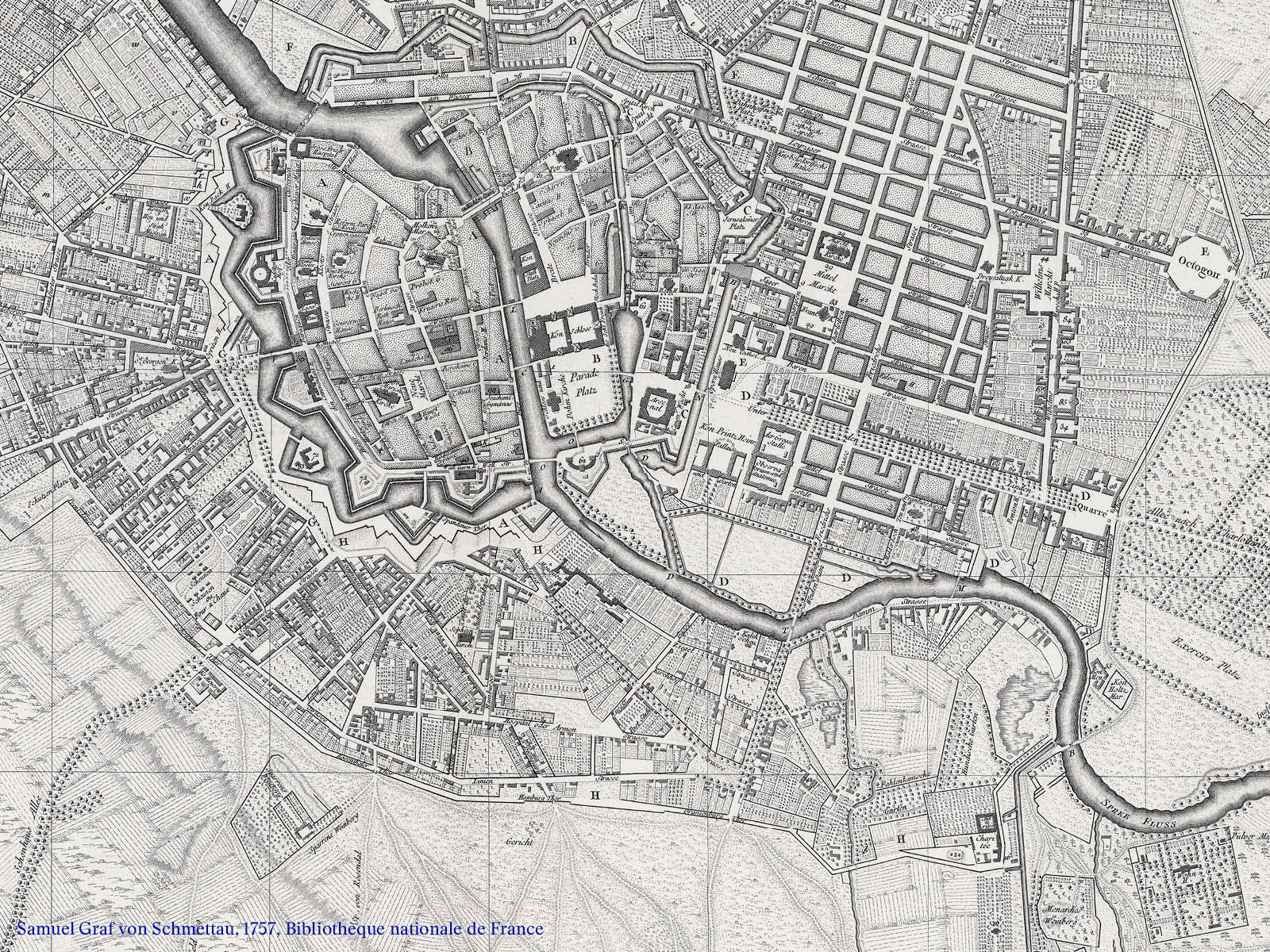

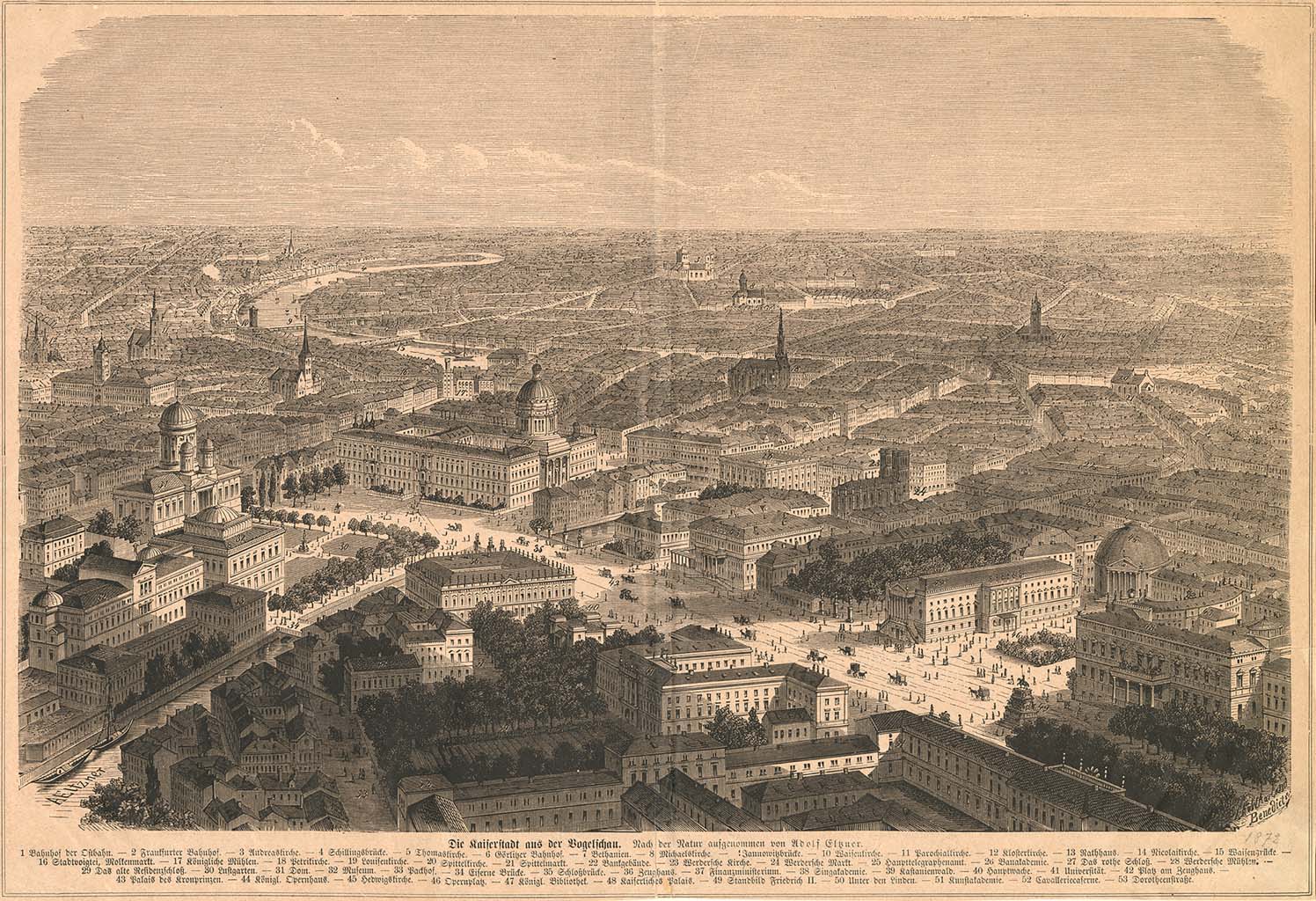

Berlin

The University

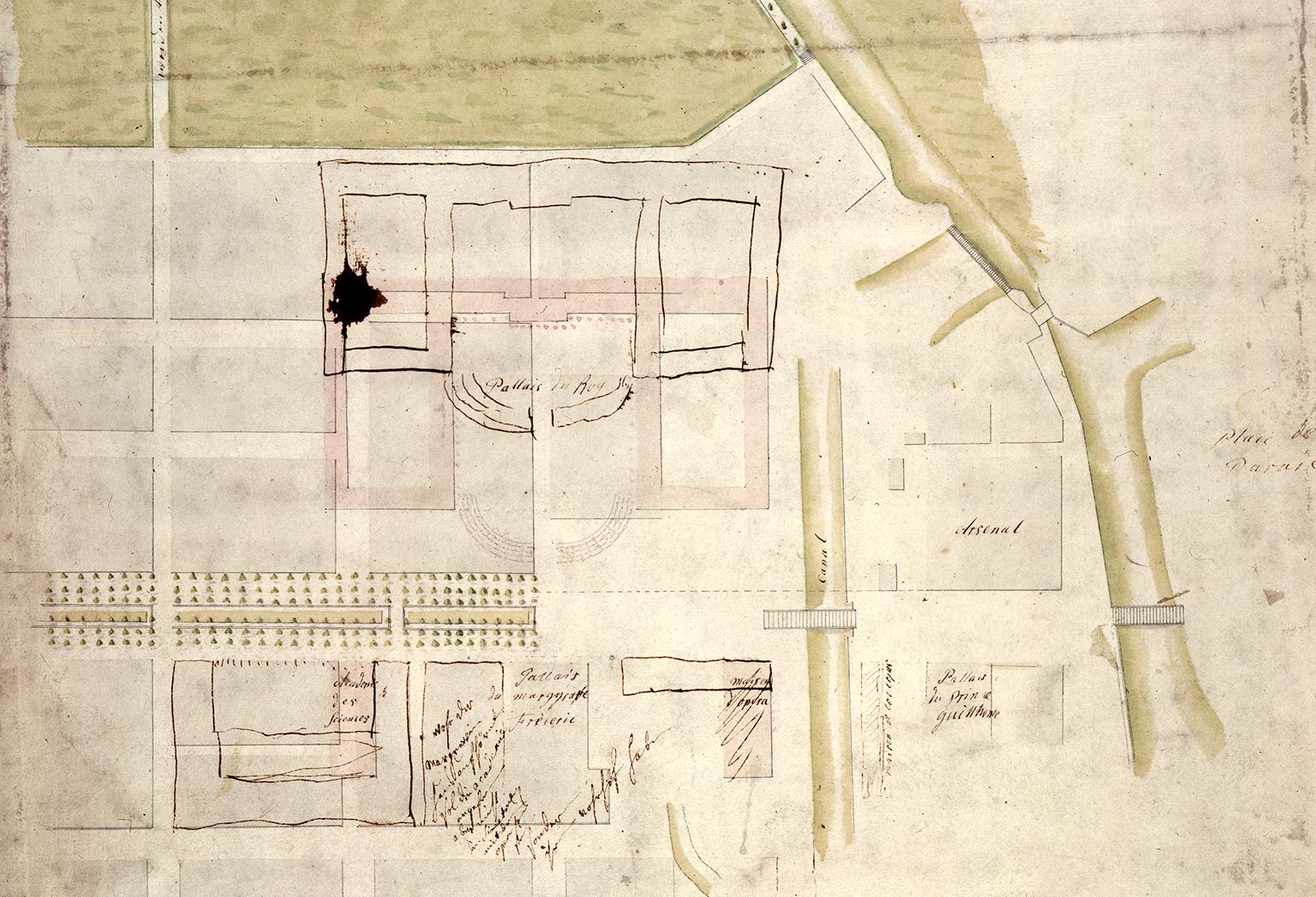

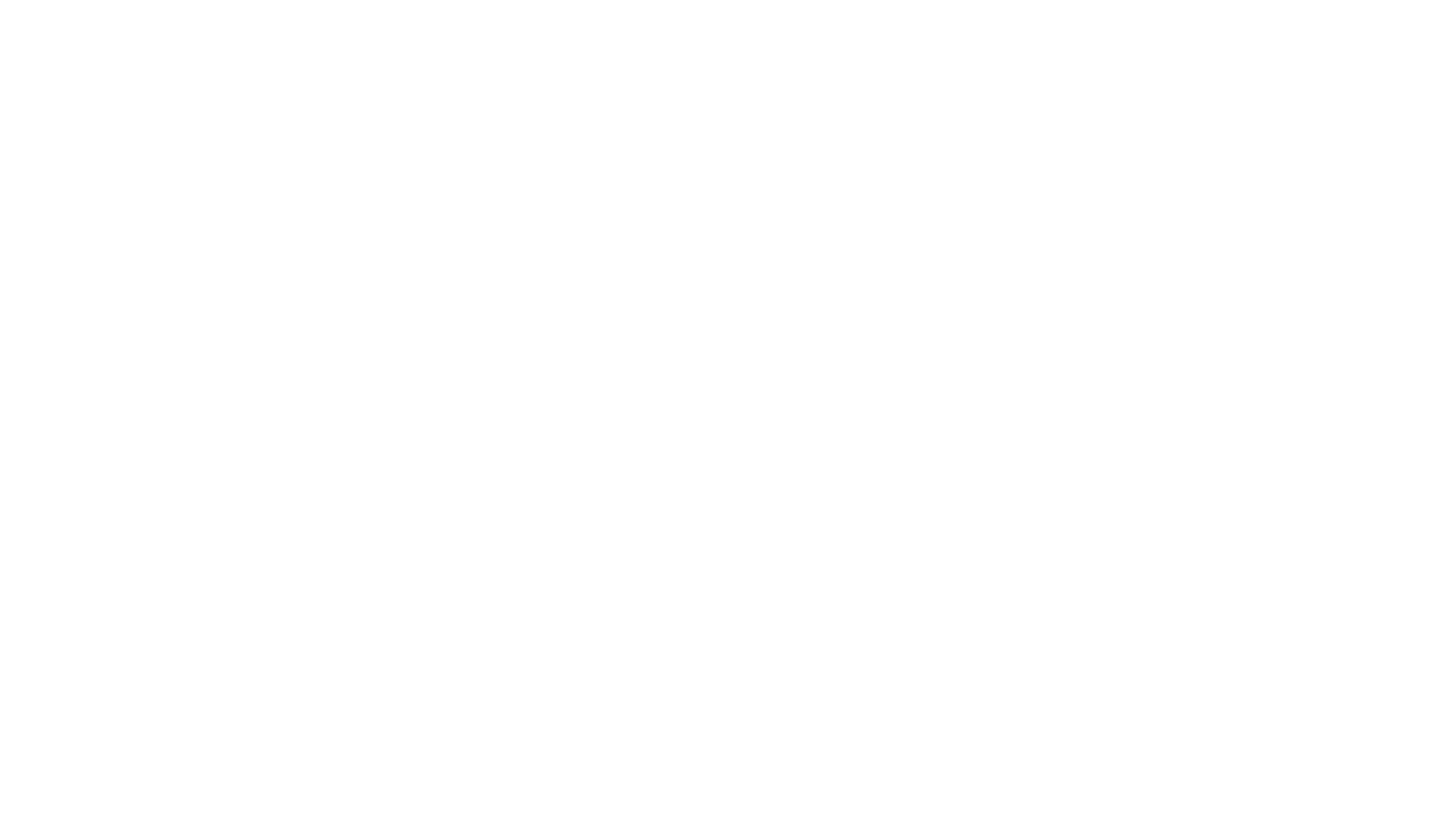

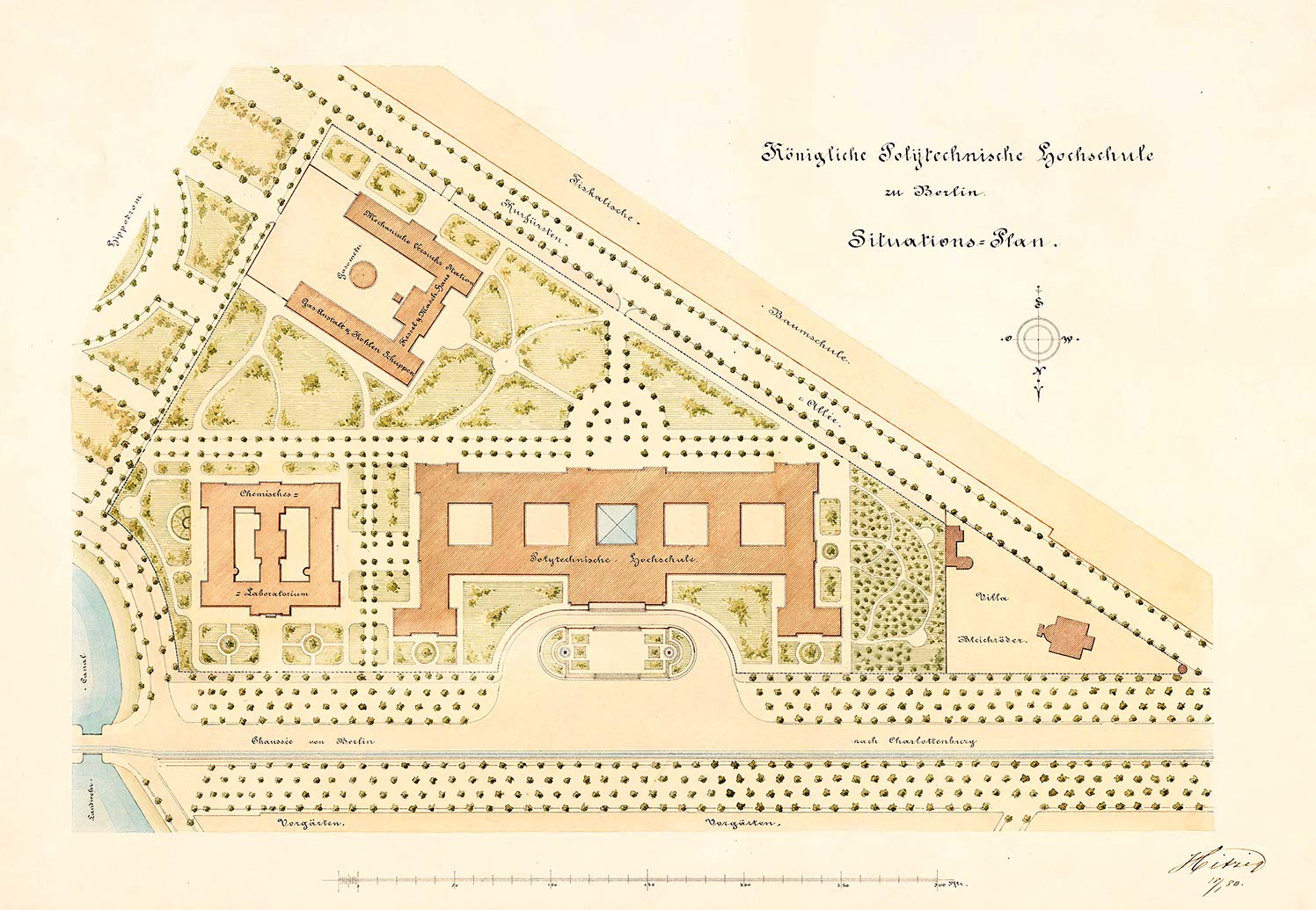

The Prussian King Frederick II inspired the square (today’s Bebelplatz) with the Opera House (today the State Opera), the Royal Library (today Faculty of Law of Humboldt University), the Hedwigs Cathedral and the Prince Heinrich Palace, built for the king’s brother. The first building was completed in 1743.

From the Palais to the University

It was not unusual for a university to have to establish itself in “foreign dwellings”: until the 19th century, many European universities had to move into buildings built for other purposes, such as noble palaces or monasteries.

London

Another example of a new university in a foreign dwelling: King’s College, London, founded in 1829, moved into Somerset House, a palace complex built in 1775 by William Chambers. The College shared the building with a number of government offices, agencies and institutions, including the Royal Academy of Arts (until 1857) and the Navy Board (until 1873).

Oslo

It is remarkable that the scheme of the castle building inspired many other new university buildings in Europe. In Oslo, for example, the Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel had a major influence on the design of the “Domus Academica” of 1852

Medicine: A Special Case

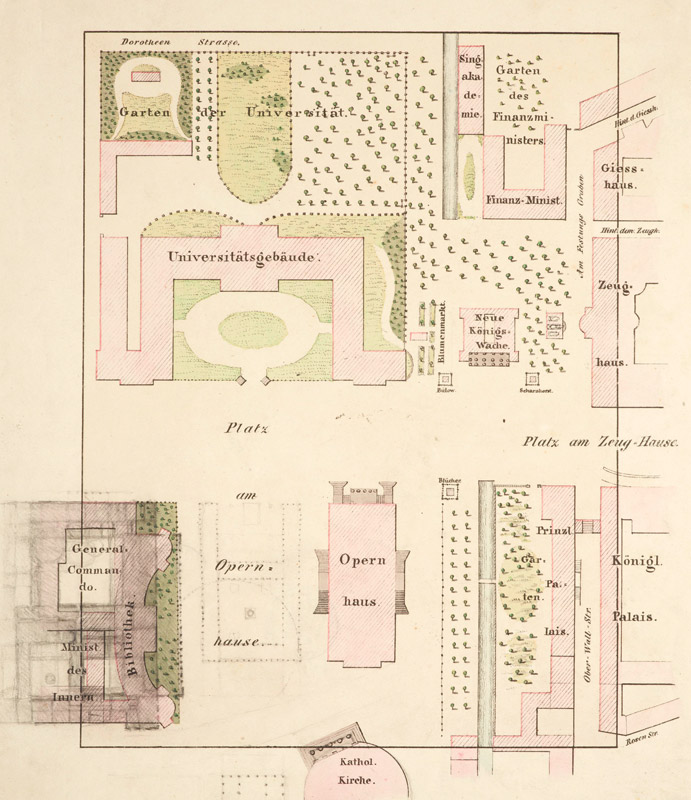

Buildings used for medical purposes were the first specific scientific buildings. The Berlin Charité, which was founded in 1710, had its own buildings and did not have to resort to existing premises.

CharitéThe Charité was founded as a plague house outside the gates of the city in 1710.

In 1831-36 the New Charité was added, a building that was to meet the increased functional requirements of the facility. Its representative character was much more reserved than the main building of the university. This building, designed by Ludwig Ferdinand Hesse, was demolished in 1905 in the course of a new planning.

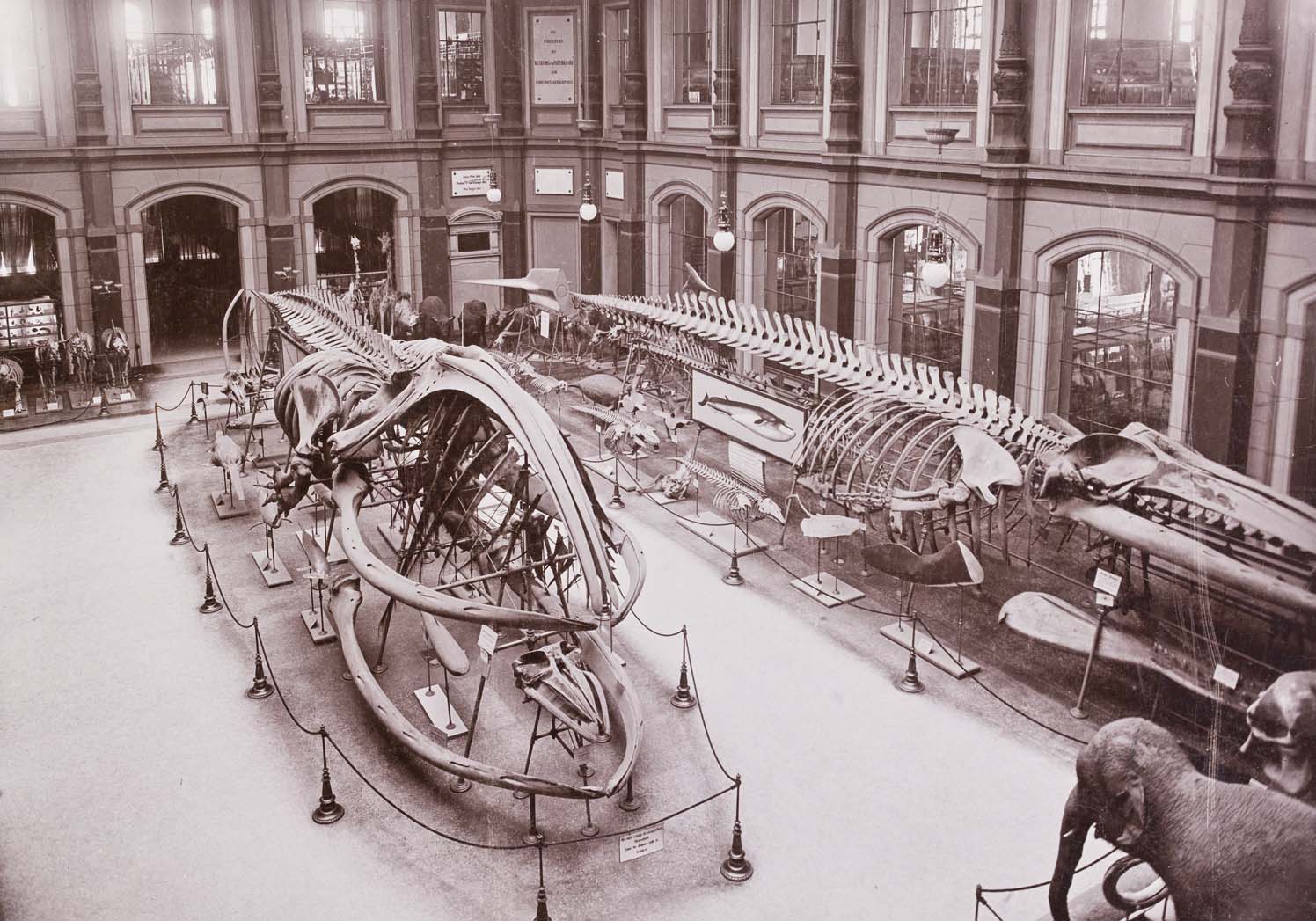

Veterinary medicine became just as important as human medicine in the 19th century. The Royal School of Veterinary Medicine was established in 1790 on the territory of the former Count Reuß’s Garden. The Villa suburbana was chosen as the building form, i.e. an arrangement consisting of several individual buildings whose centre forms an architecturally striking main building on a hill. The design of the area was modelled on the English landscape garden.

Charité Clinic Buildings

Between 1897 and 1917 a new modern clinic complex was built: the Charité, as it is still visible today. Here the surgical clinic from 1904

2 Architectures of Education

2 Architectures of Education

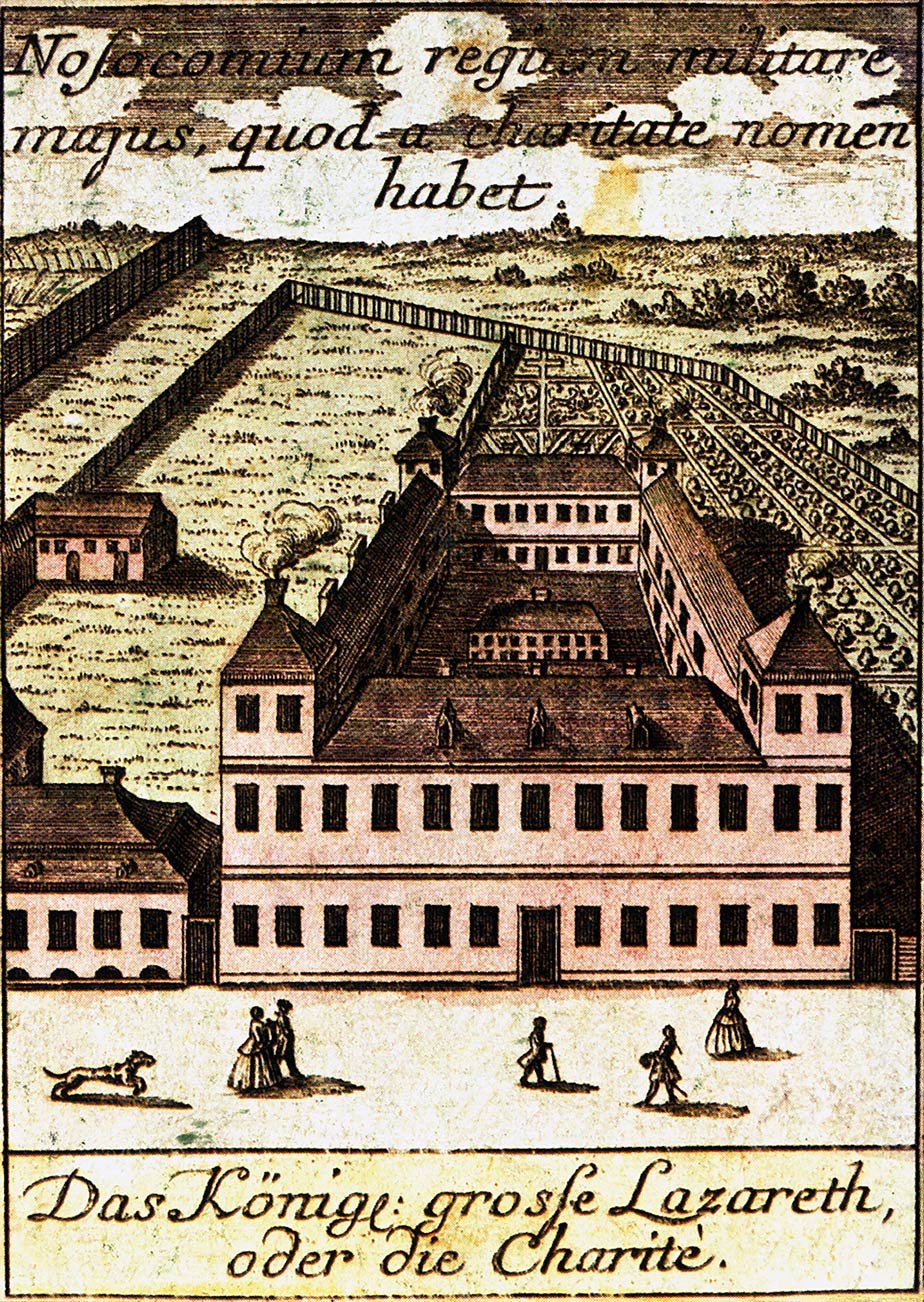

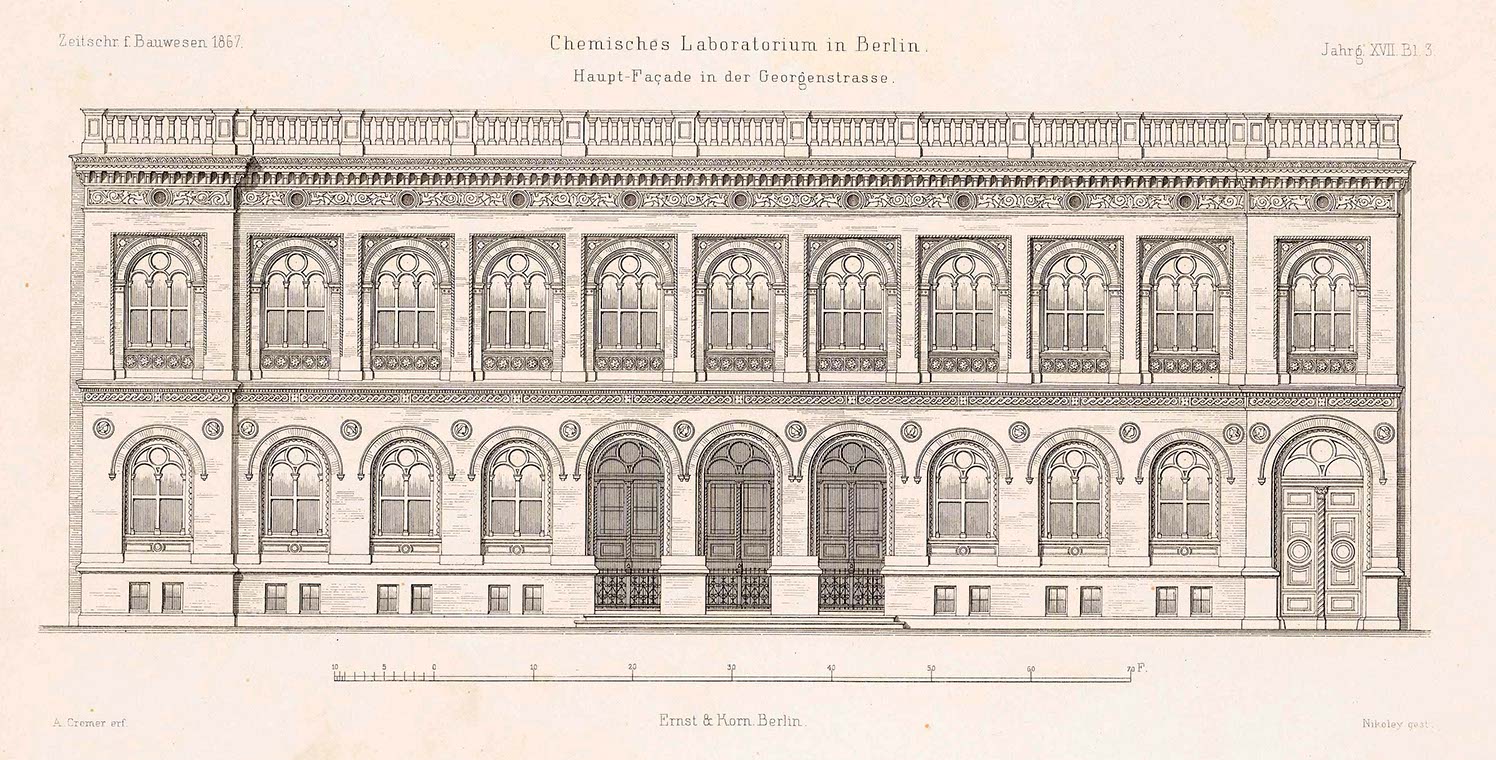

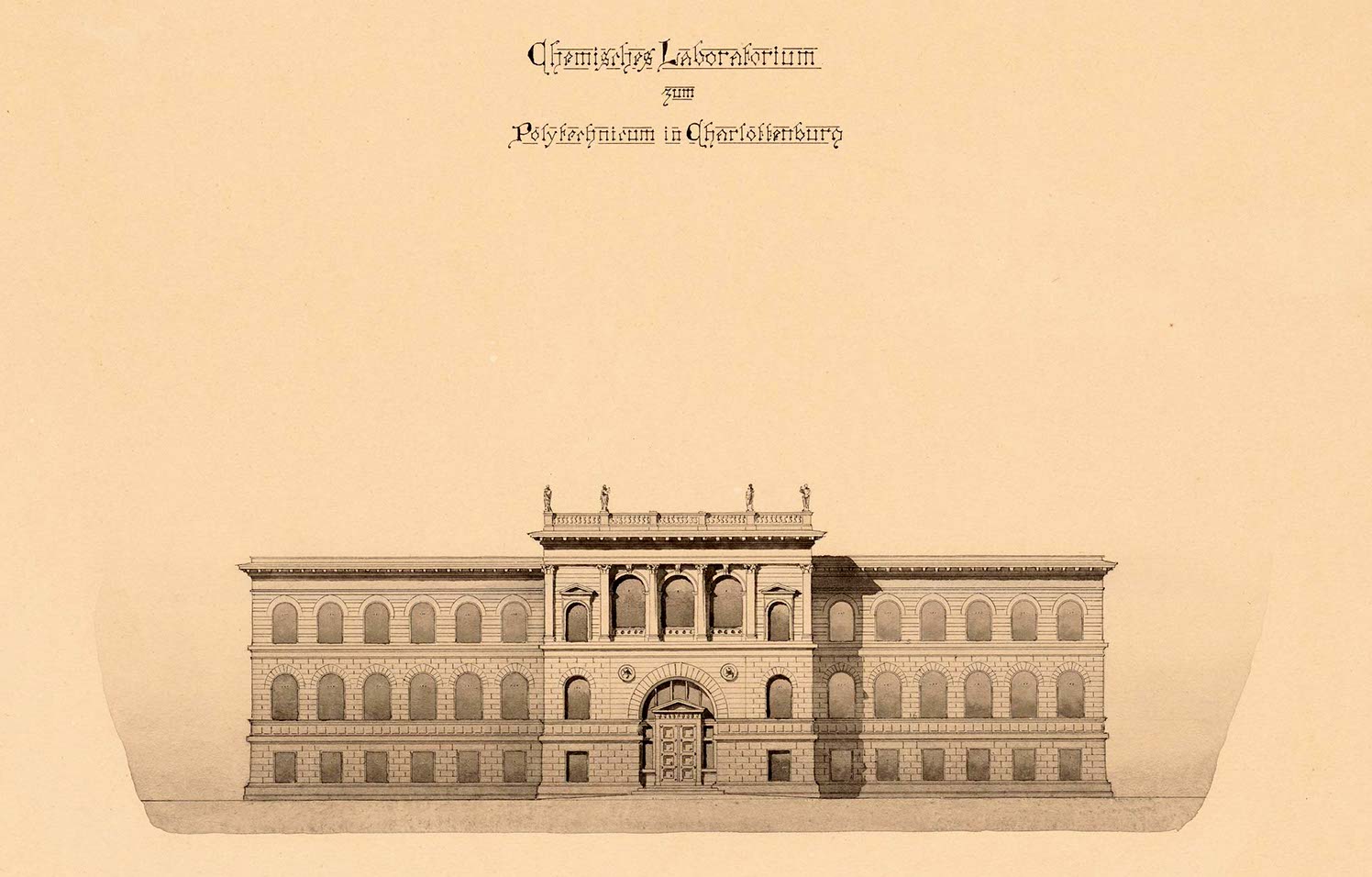

Technical Colleges

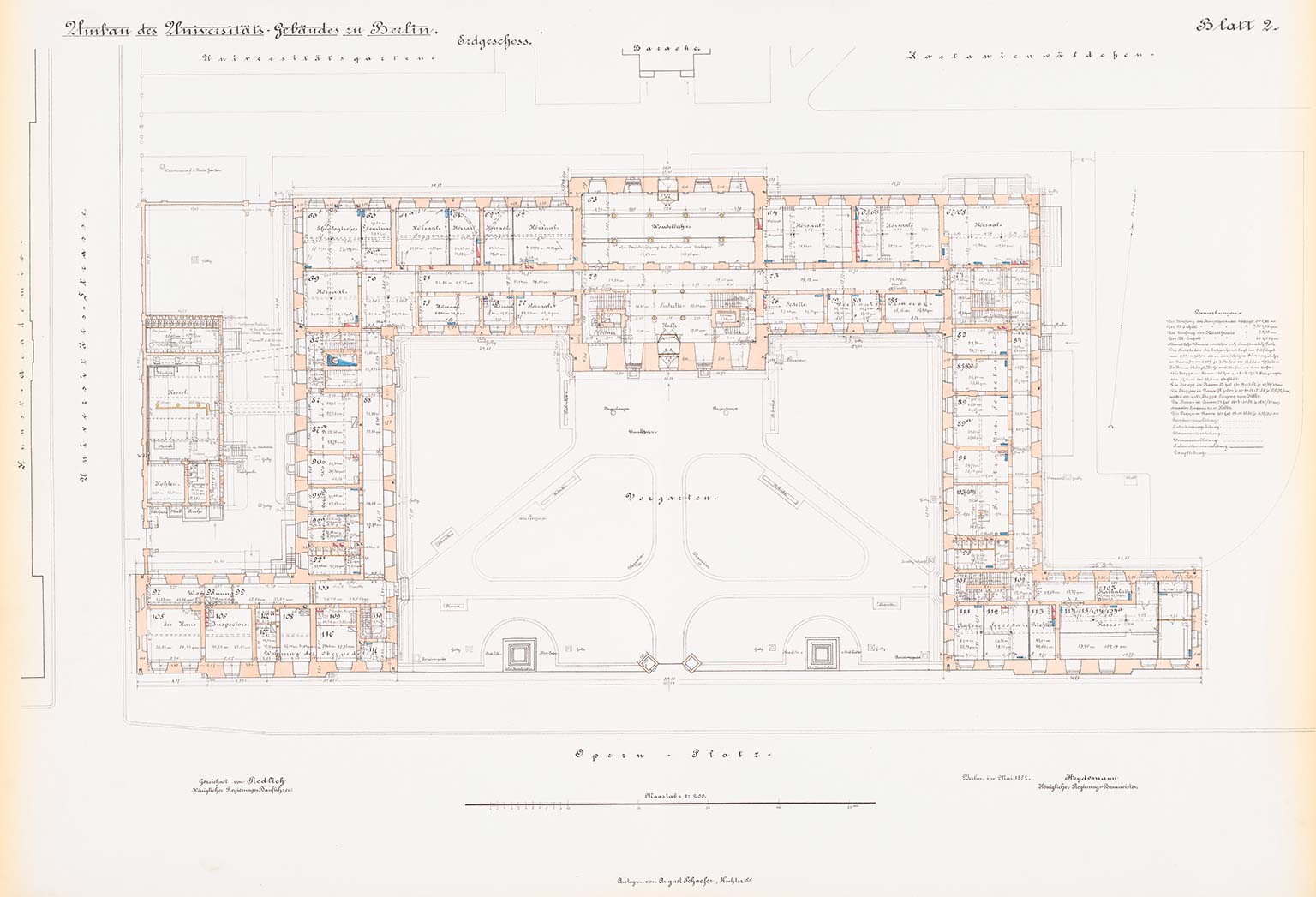

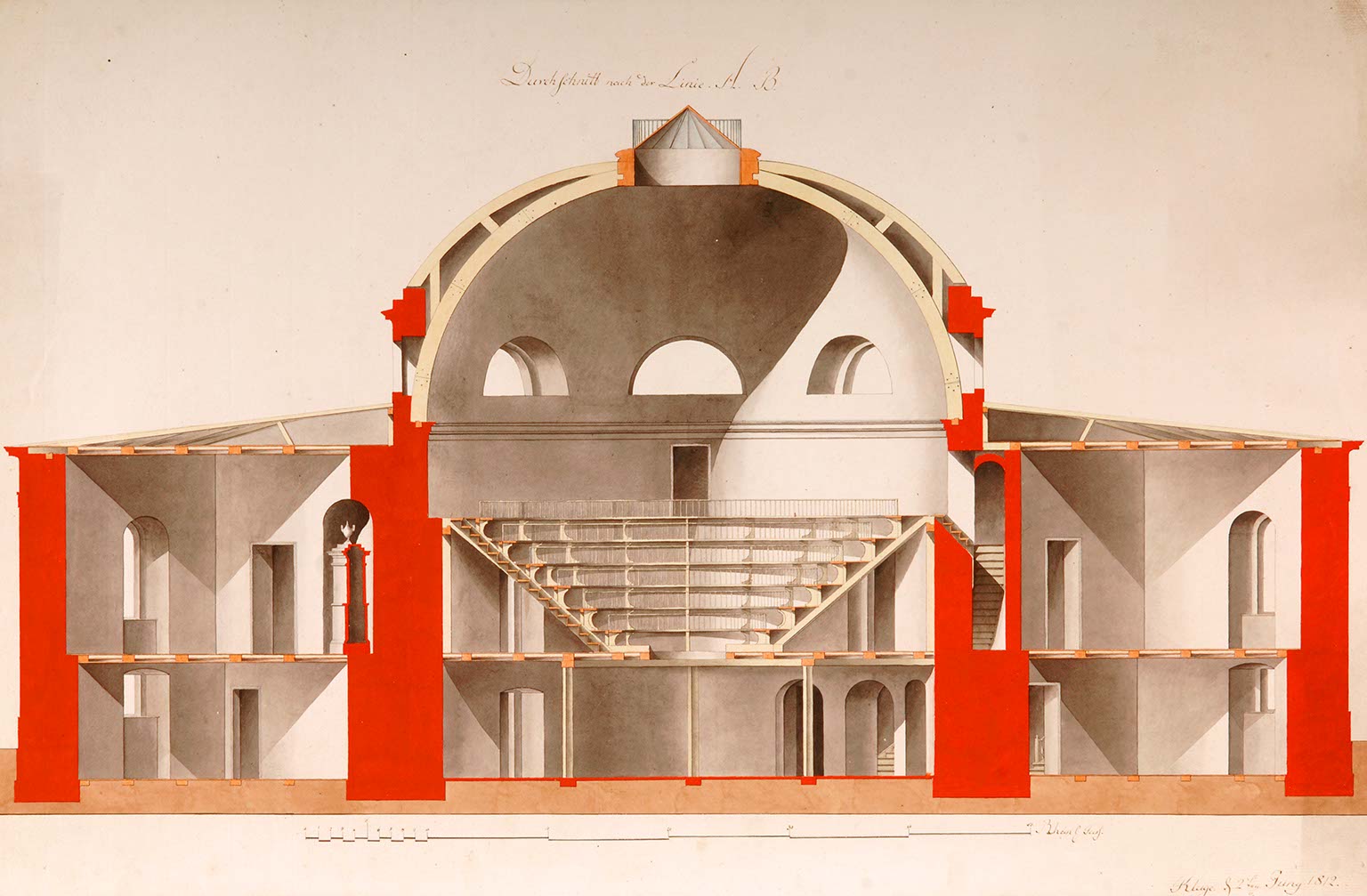

The widespread reuse of existing buildings was only replaced by a new university architecture after 1850, especially to give expression to technical sciences. The representative main buildings took up the baroque castle scheme and combined it with the idea of the university, e.g. the ballroom became the festive auditorium. Instead of offering functionally differentiated spaces for the different disciplines, it was more important to work in the shared house of science.

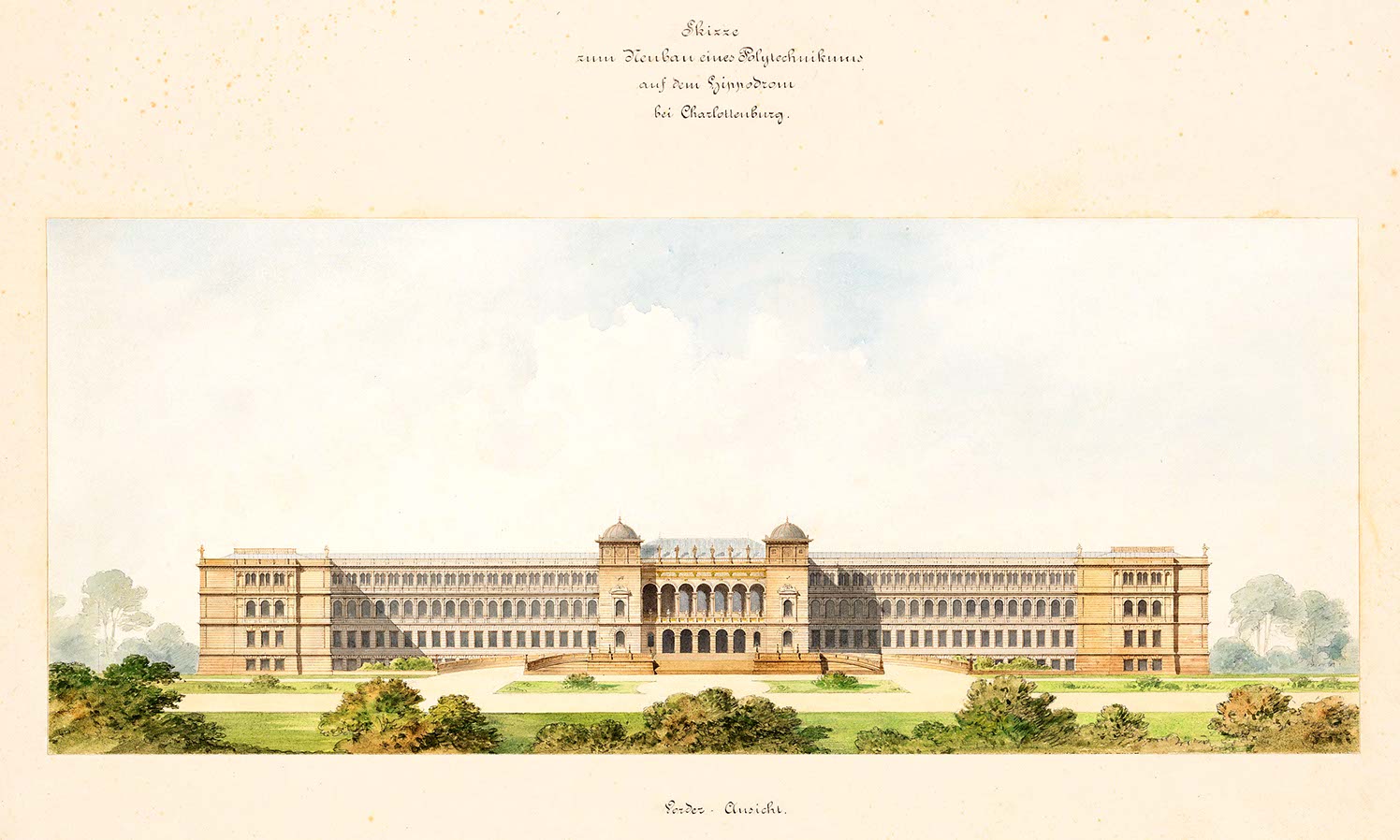

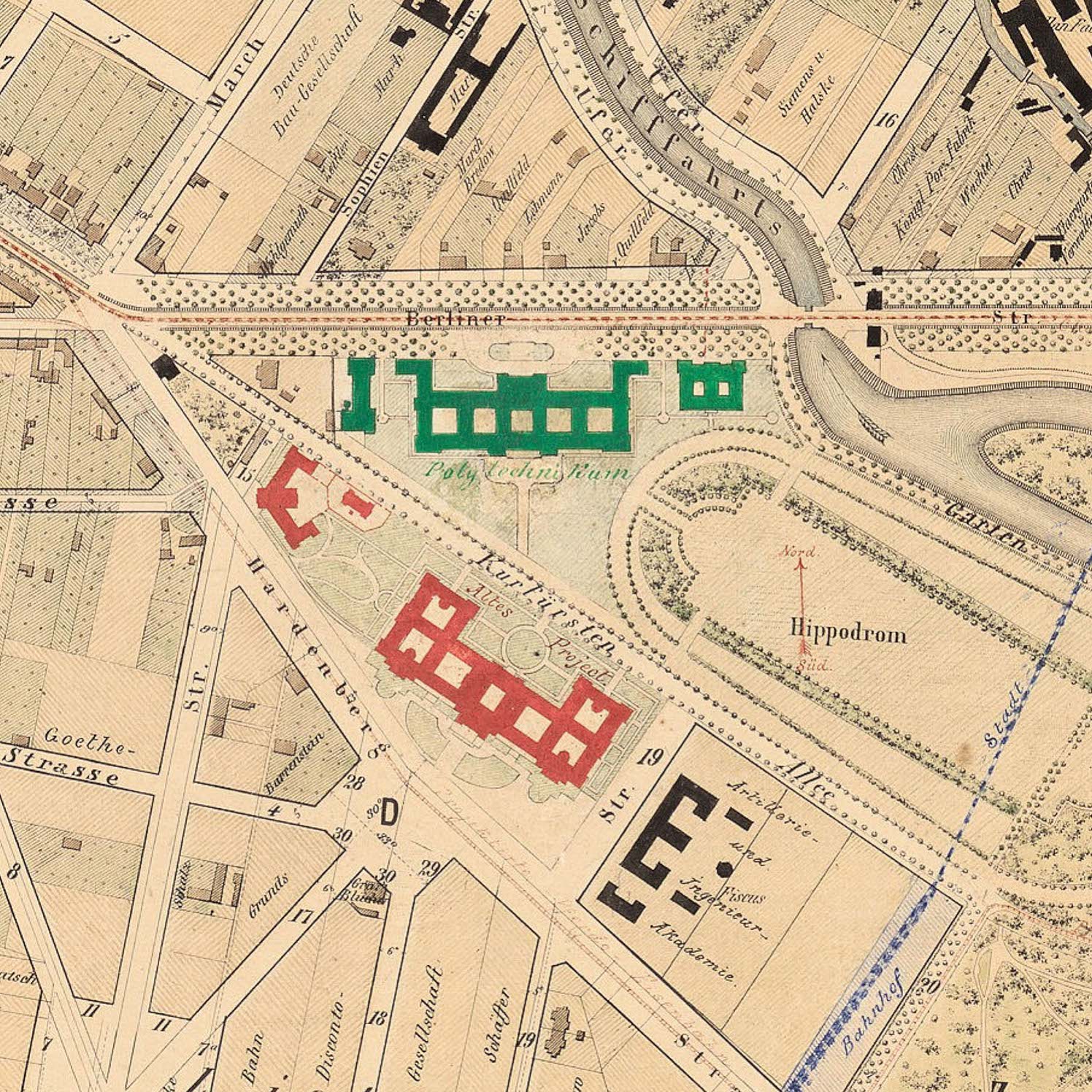

Technical College in CharlottenburgThe design by the director of the Bauakademie Richard Lucae from 1877.

After his death in 1878, the president of the Academy of Arts, Friedrich Hitzig, took over and made the central pavilion wider and more massive and had gave the three floors increased visibility through a “never before dared change of colour”.

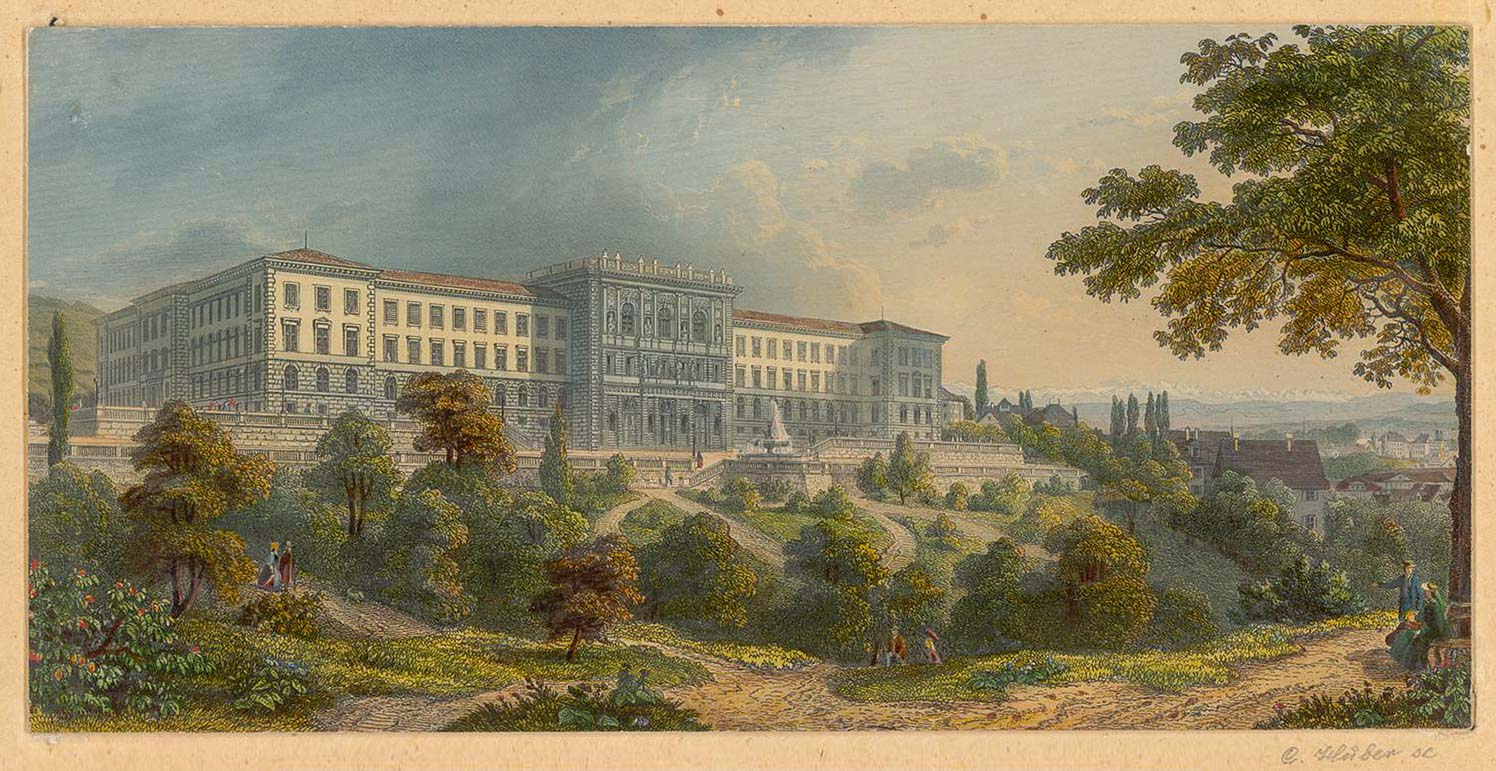

Zurich

Gottfried Semper’s Polytechnic in Zurich of 1864 became a model for a monumental educational architecture in Europe, especially for the technical universities in the era of high industrialization and Gründerzeit.

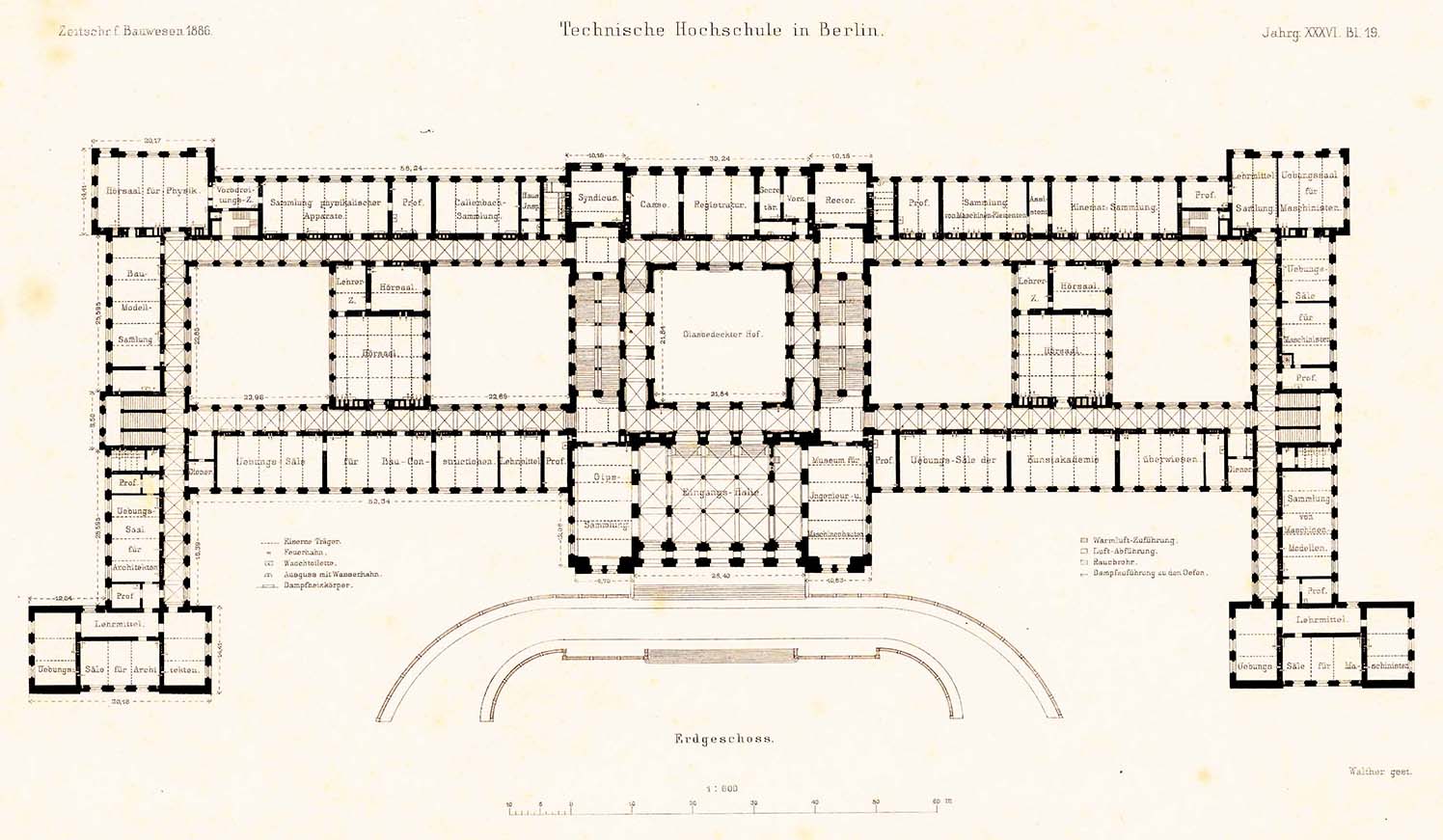

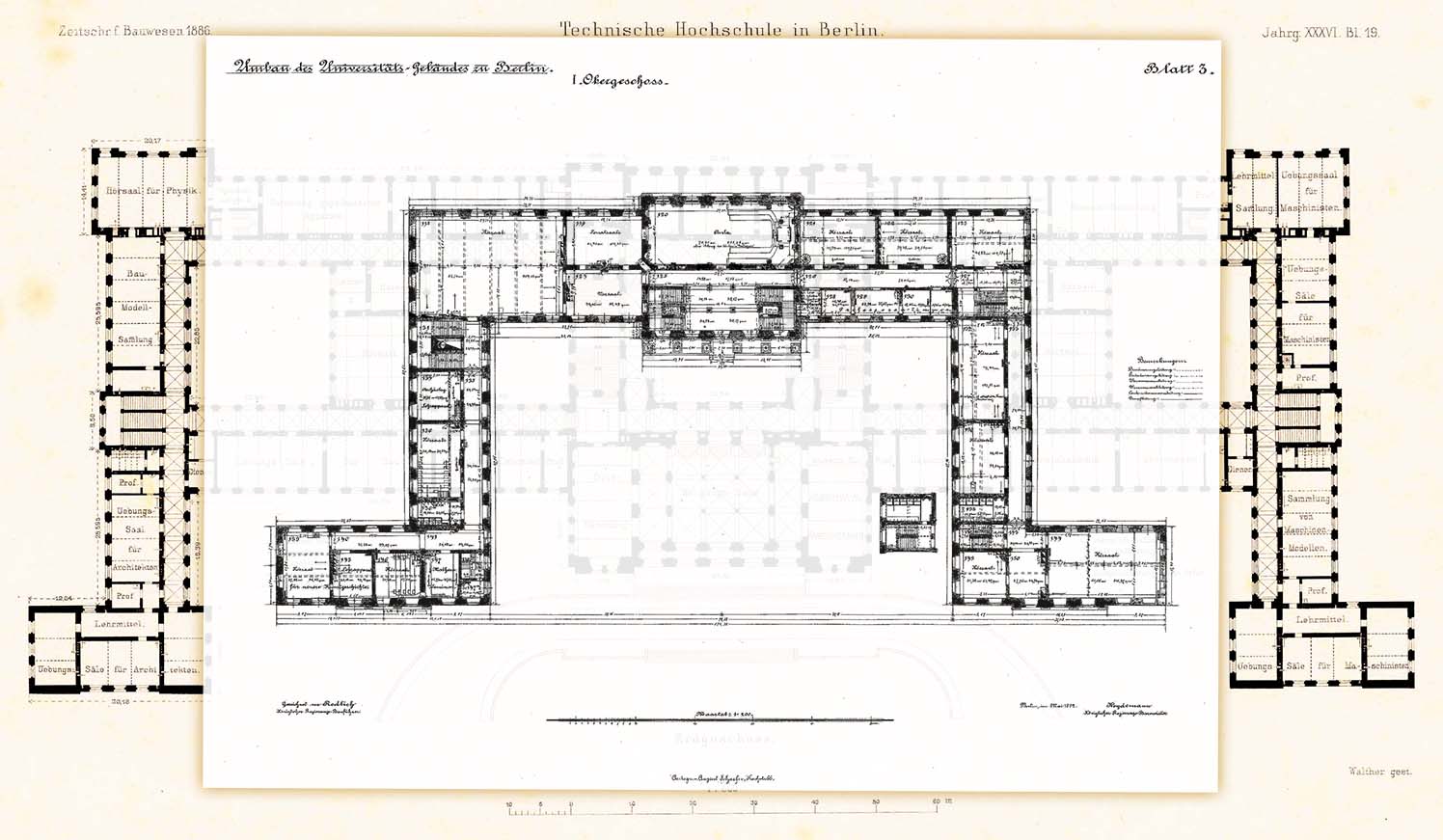

Technical College in CharlottenburgAll departments (except chemistry) were situated on three floors in the main building. Large areas are occupied by collections, which were open to the public such as the Gypsum Collection and the Museum of Mechanical Engineering on both sides of the vestibule, and the Beuth Schinkel Museum, the Callenbach Collection or the geological teaching collection.

Size comparison with the main building of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-University, the later Humboldt-University.

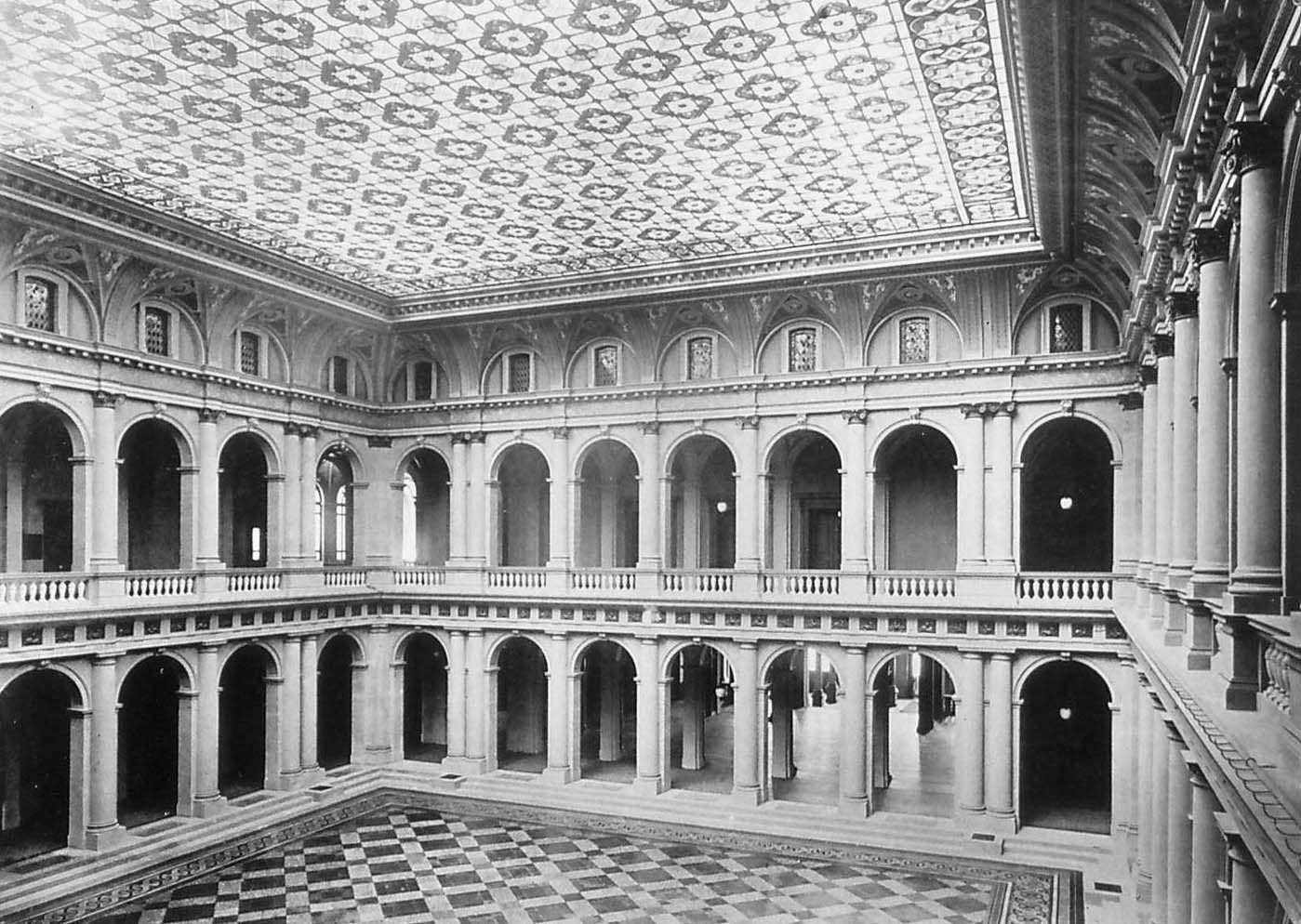

Berlin The atrium of the main building of the Royal Technical College of Berlin, which was completed in 1884 is an example of the representative architecture for an academic building of this unprecedented size in the German Empire.

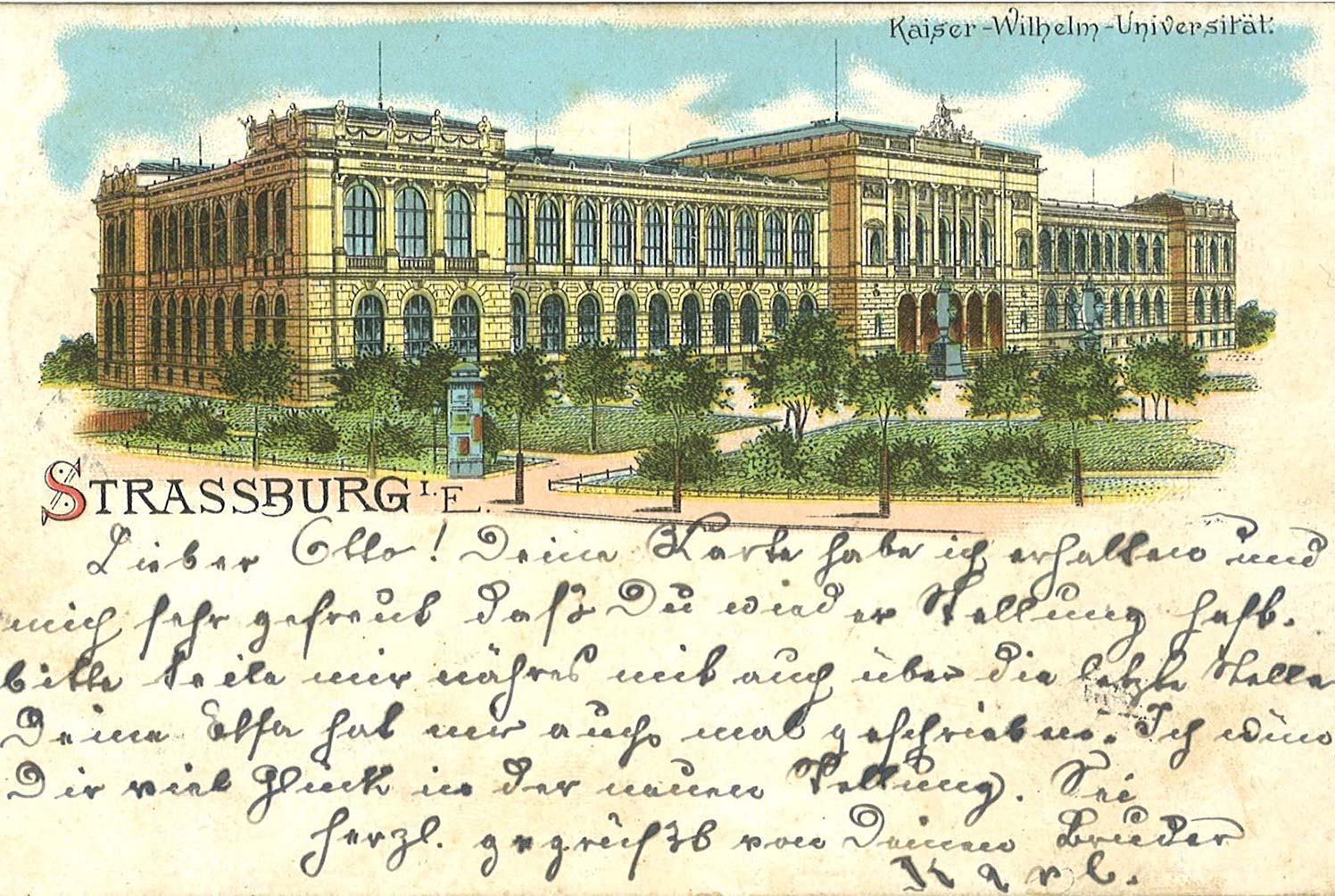

StrasbourgThe Kaiser Wilhelm University was newly founded in 1872 at Strasbourg after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71. Here again a monumental main building represented a national ambition (that was lost again after the First World War). Architecturally, the proximity to the Charlottenburg Technical University is obvious, for example in the style of the large atriums.

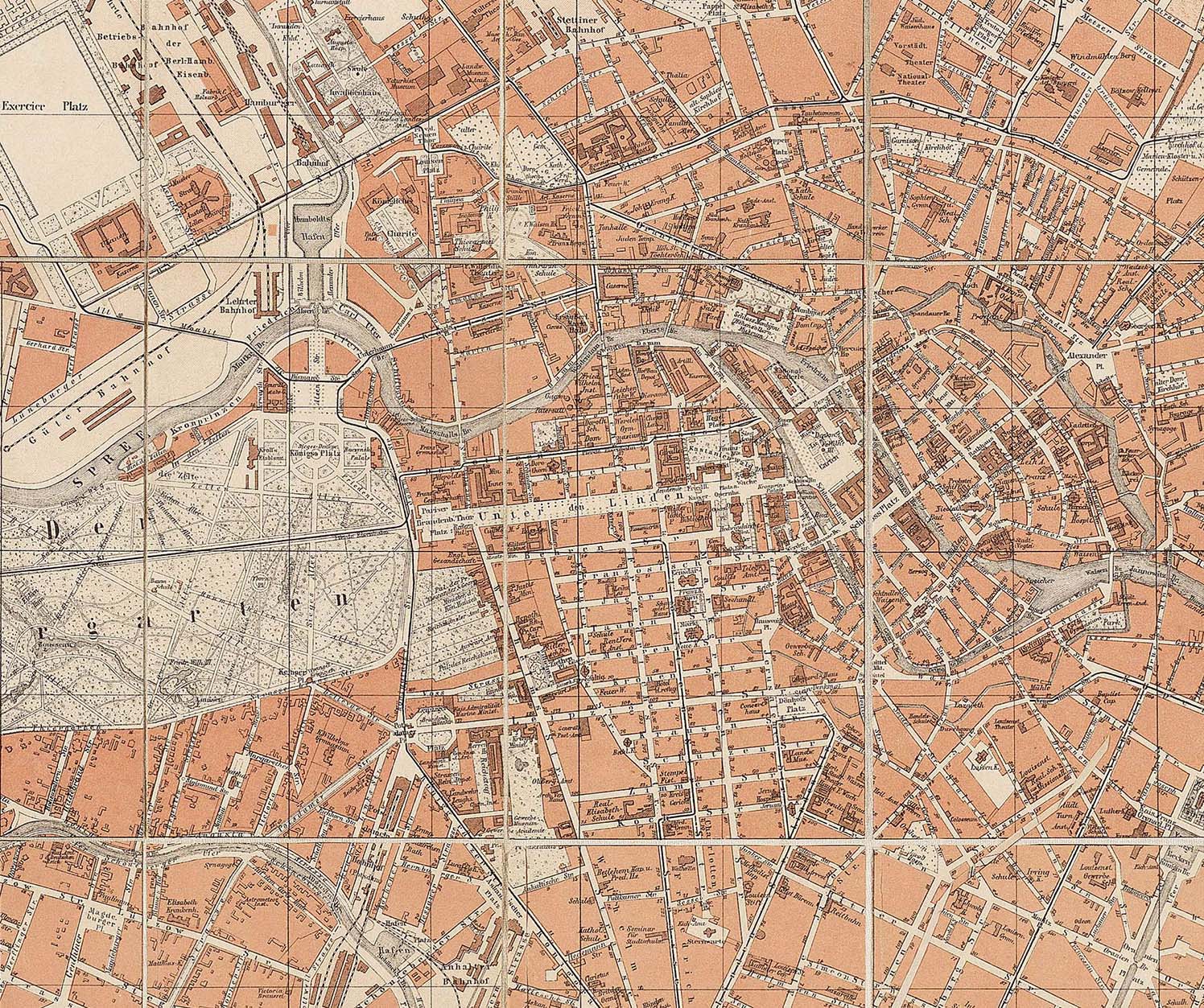

Growing in the City

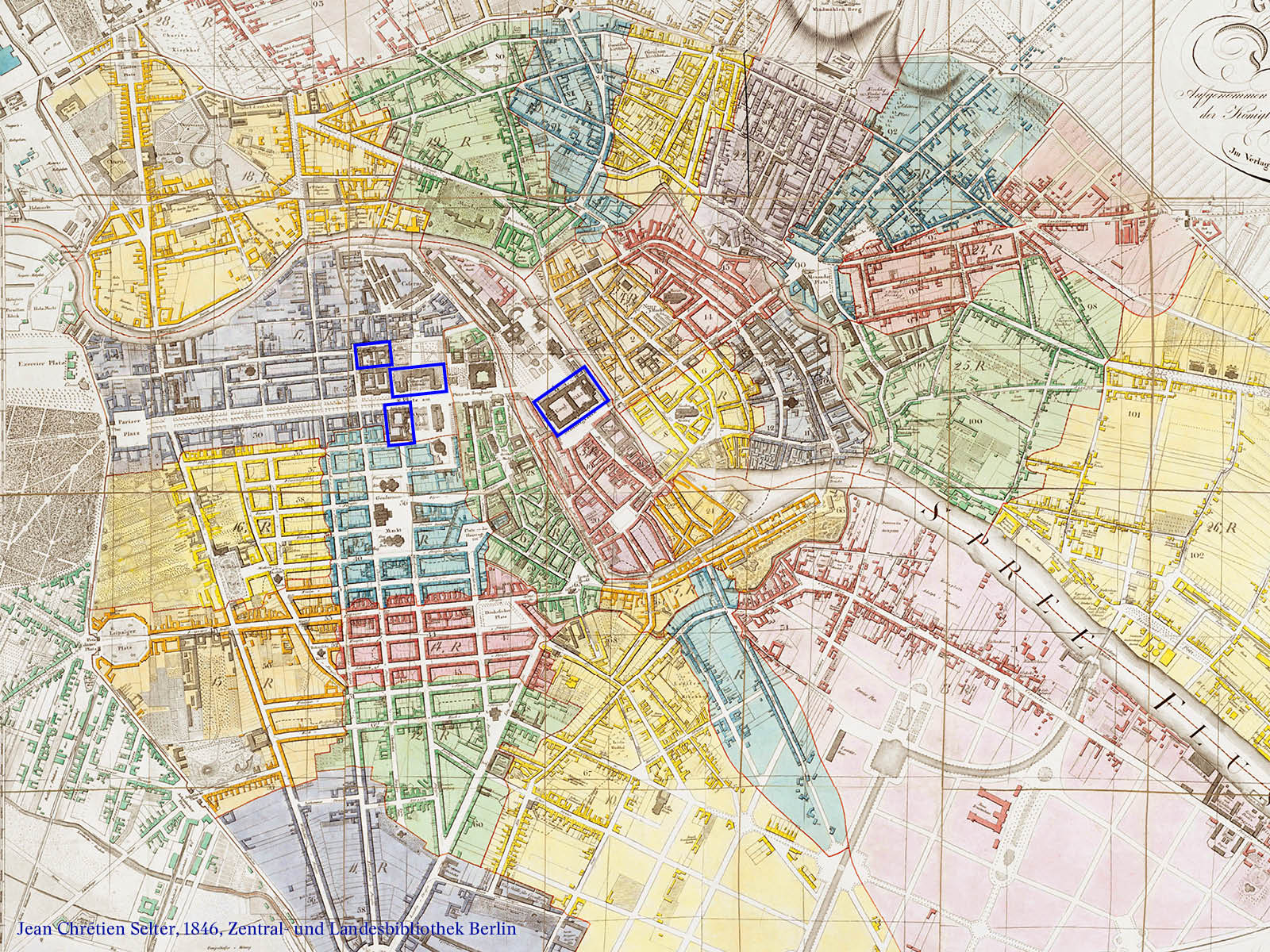

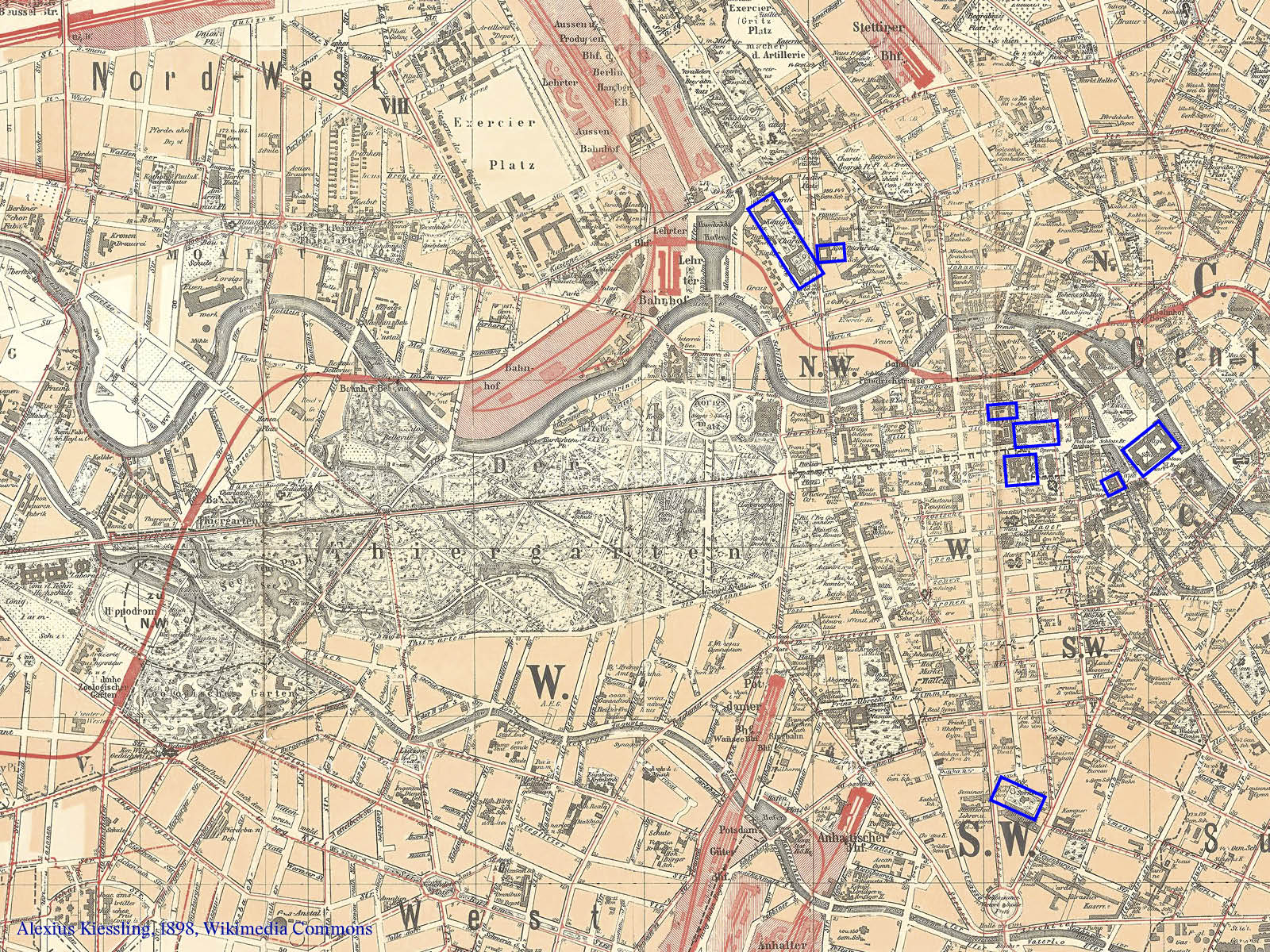

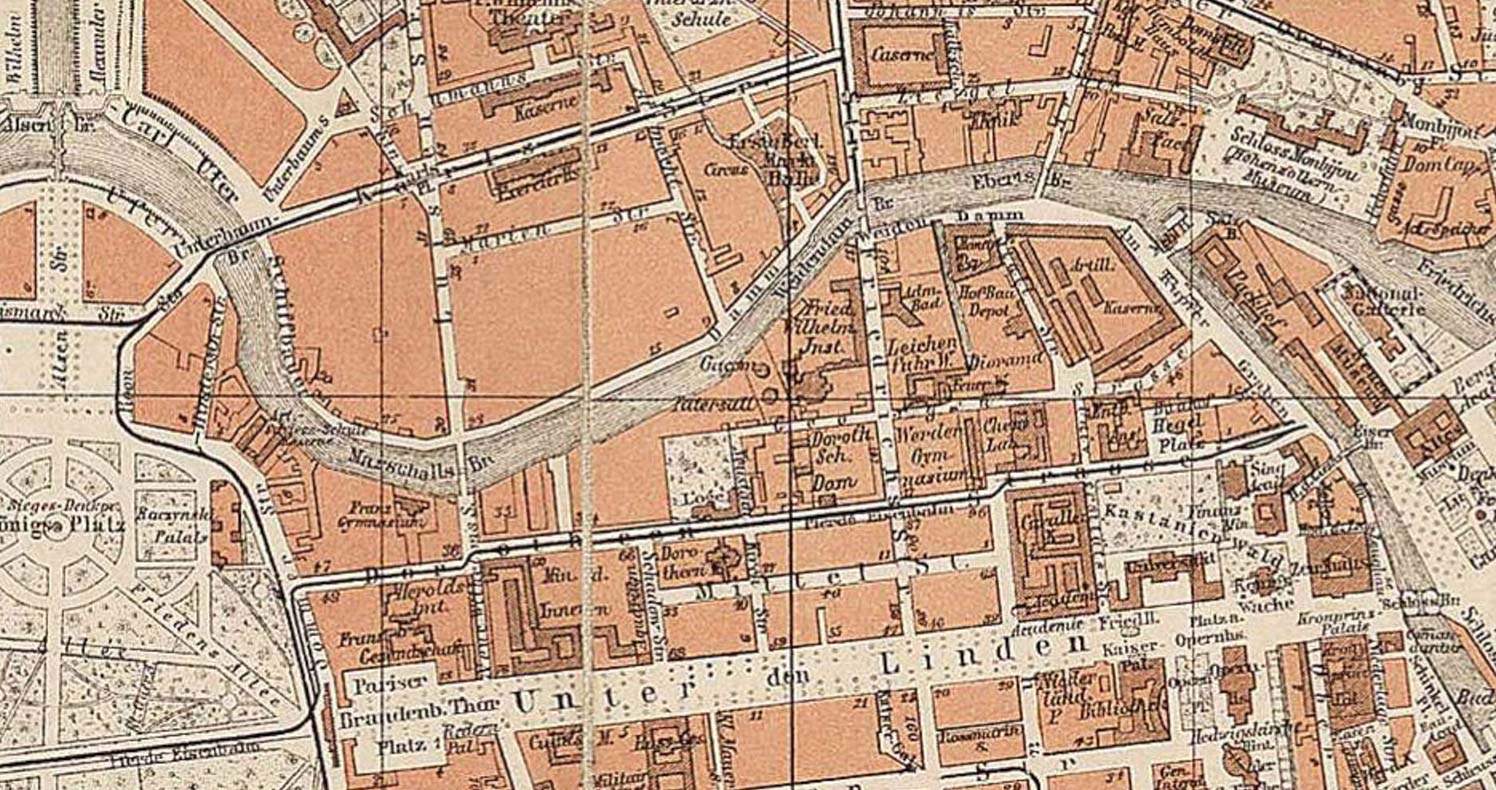

Both at the University of Unter den Linden and at the Technical College in Charlottenburg, one discipline was the first to claim its own building: chemistry. Their example was to determine the later differentiation into various scientific districts. In Mitte, a development along Dorotheenstrasse was laid out, in Charlottenburg the chemistry department expanded the main building into an axis ensemble, which was later continued with the extension building.

Berlin University: Dorotheenstraße

Due to its location in the densely developed new city center, the expansion of the Berlin University from the 1860s on with institutes and the library proved difficult and it was necessary to gradually move to more distant locations.

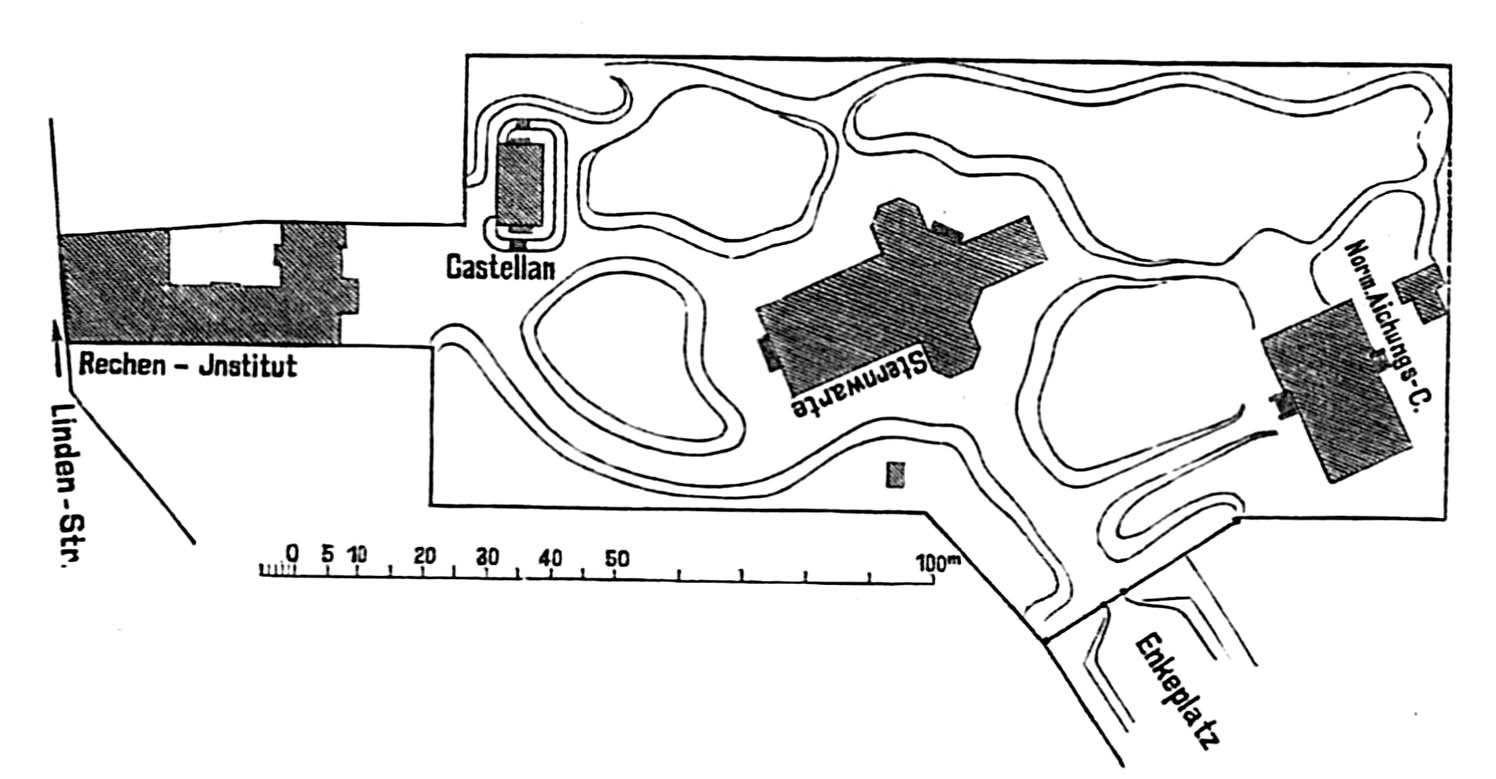

1 Main building (1753)

2 Institute of Chemistry 1867

3 University Library 1874

4 Natural Sciences 1878

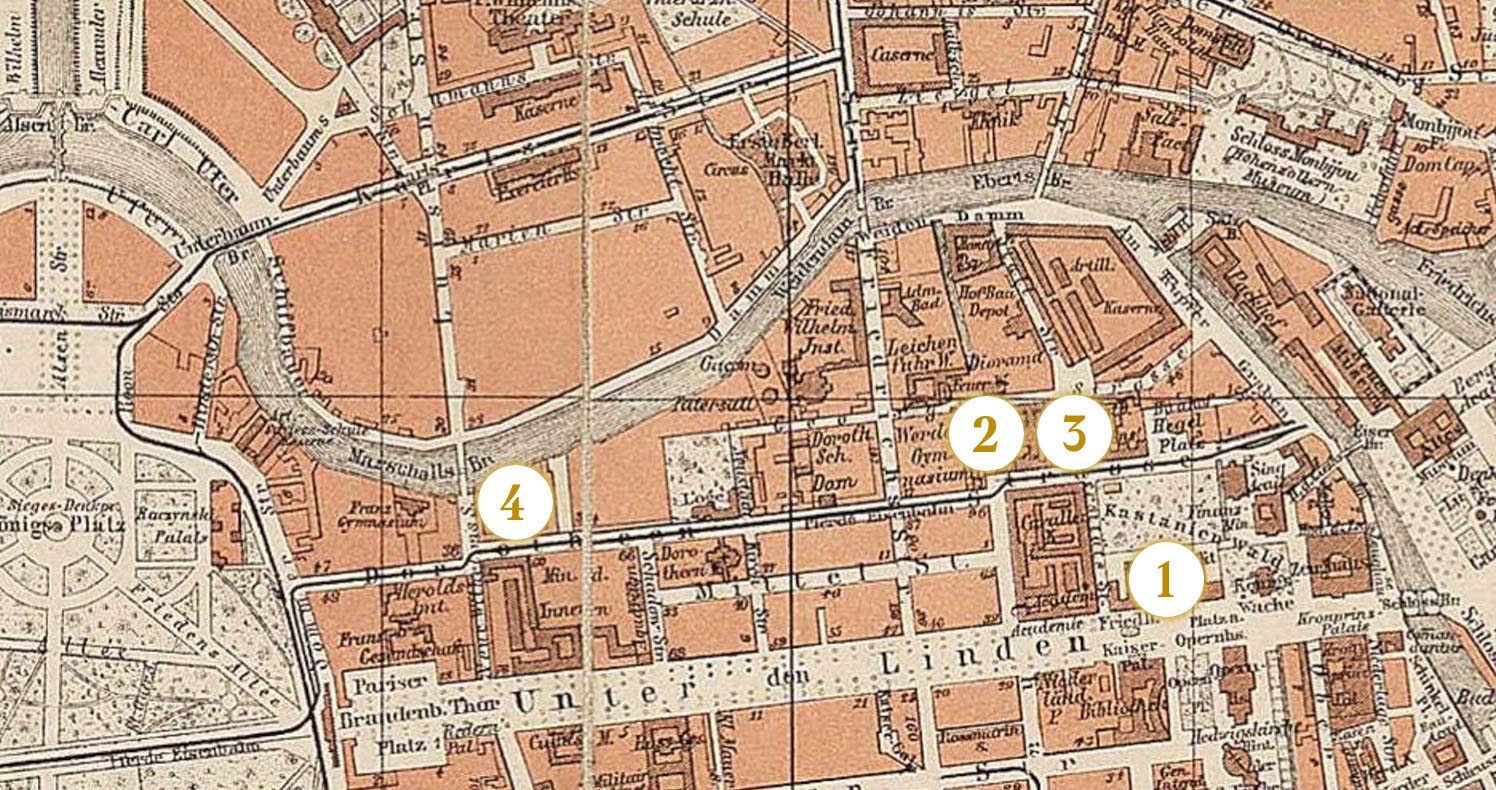

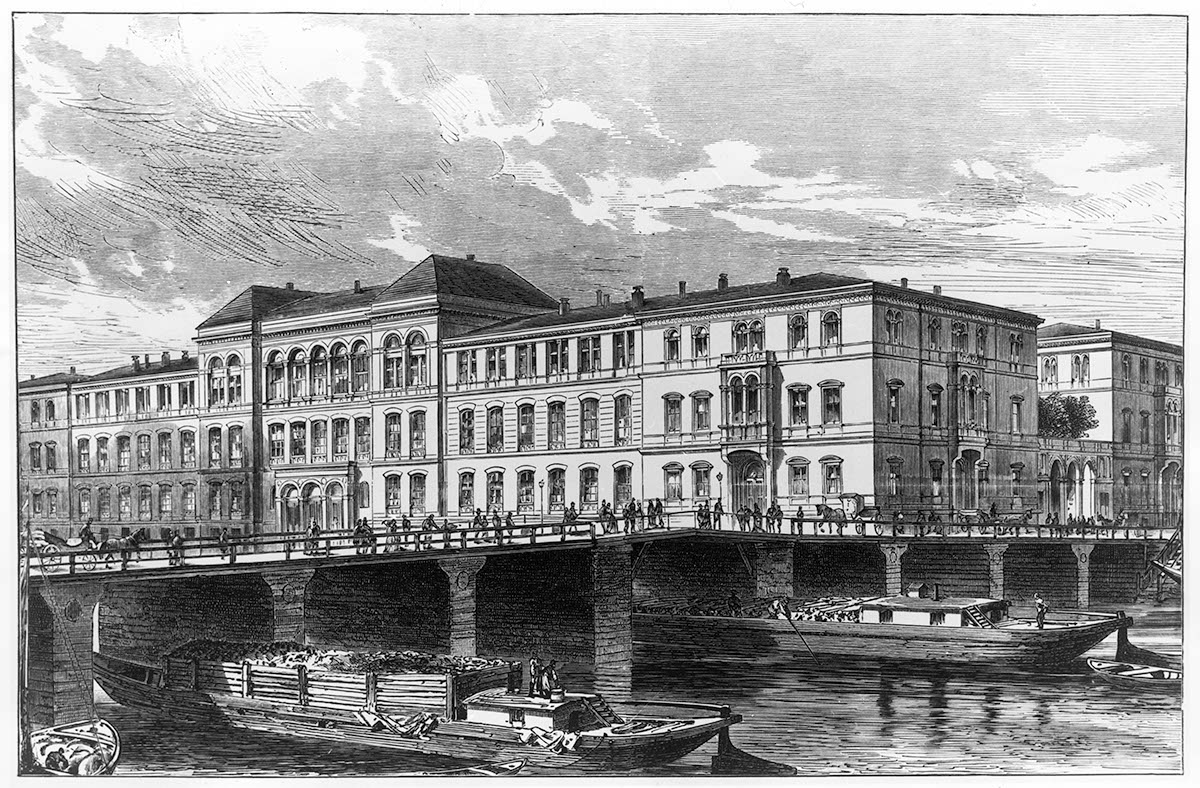

1865 Chemical Institute of the University

The chemist August Hofmann could only be recruited for Berlin with the promise to have a new laboratory built according to his wishes. He had already planned laboratories in London and Bonn. The need for light and ventilation can be seen in the unusually large window areas.

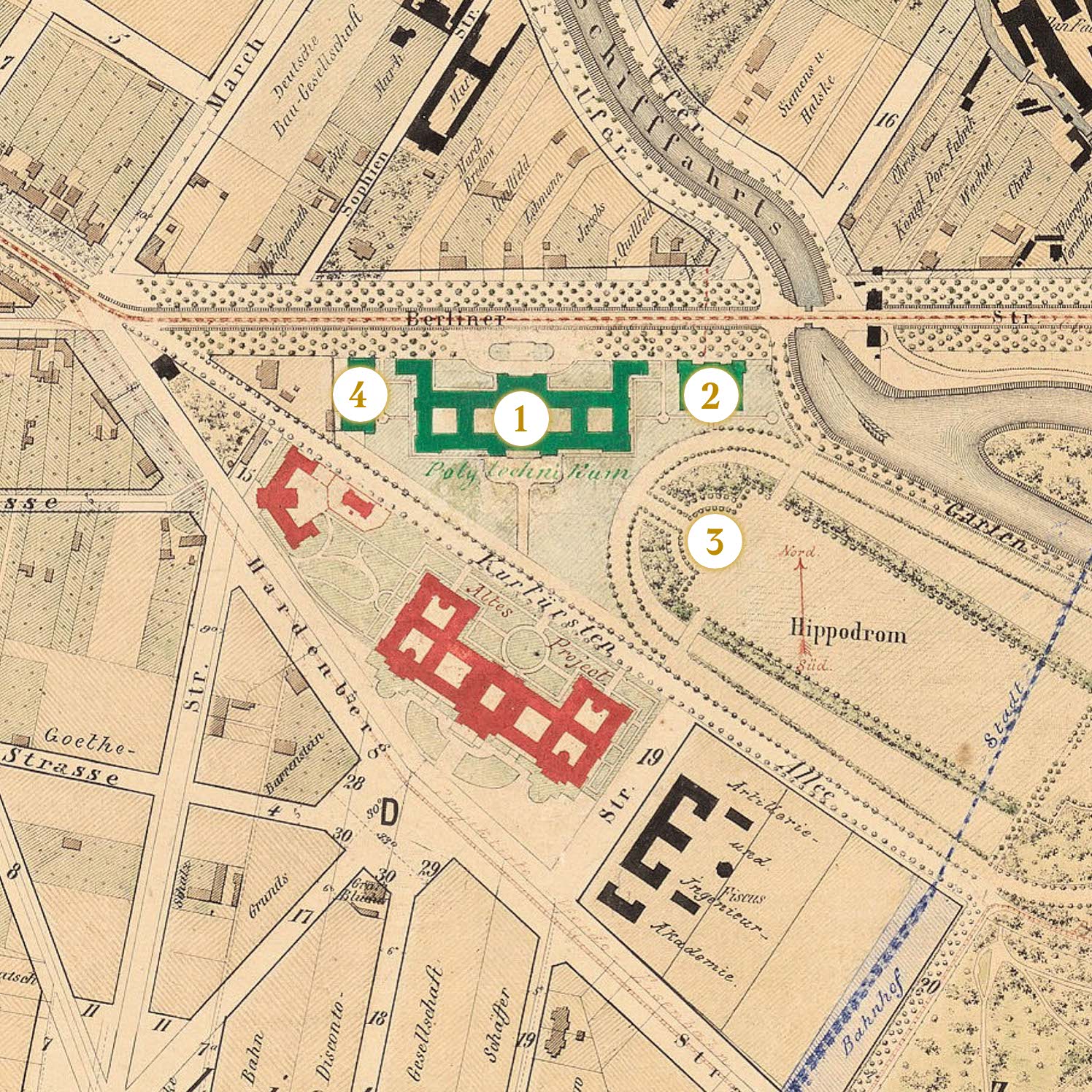

1884 Chemical Laboratory of the Technical College

The Chemical Institute was built east of the main building, as the wind was mostly from the west. With the rapid development of chemistry, the structural requirements also changed quickly, so that Julius Raschdorff was not inspired by Hoffmann's laboratory, but took up suggestions from Giessen, Zurich, London and, as far as the floor plan was concerned, Vienna.

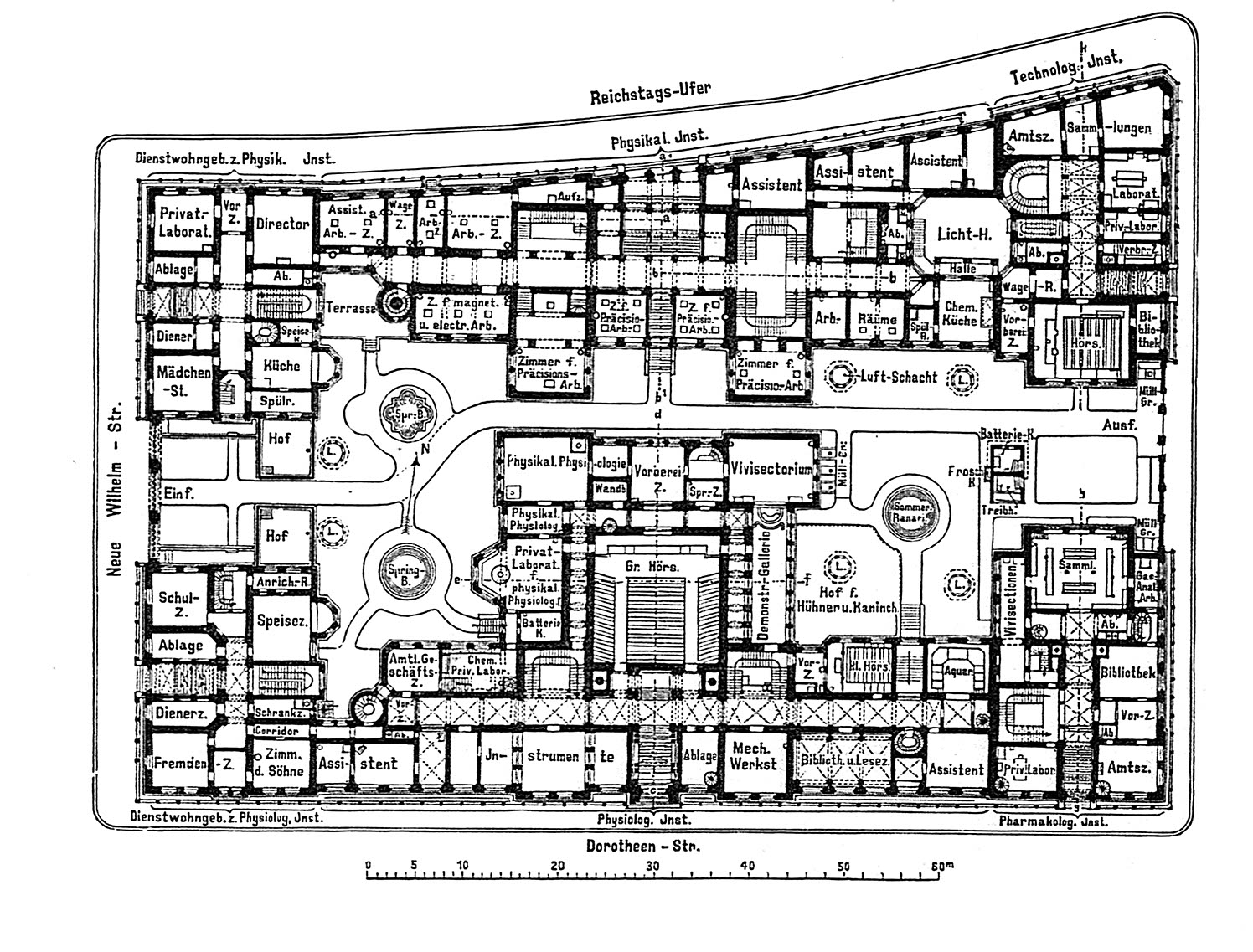

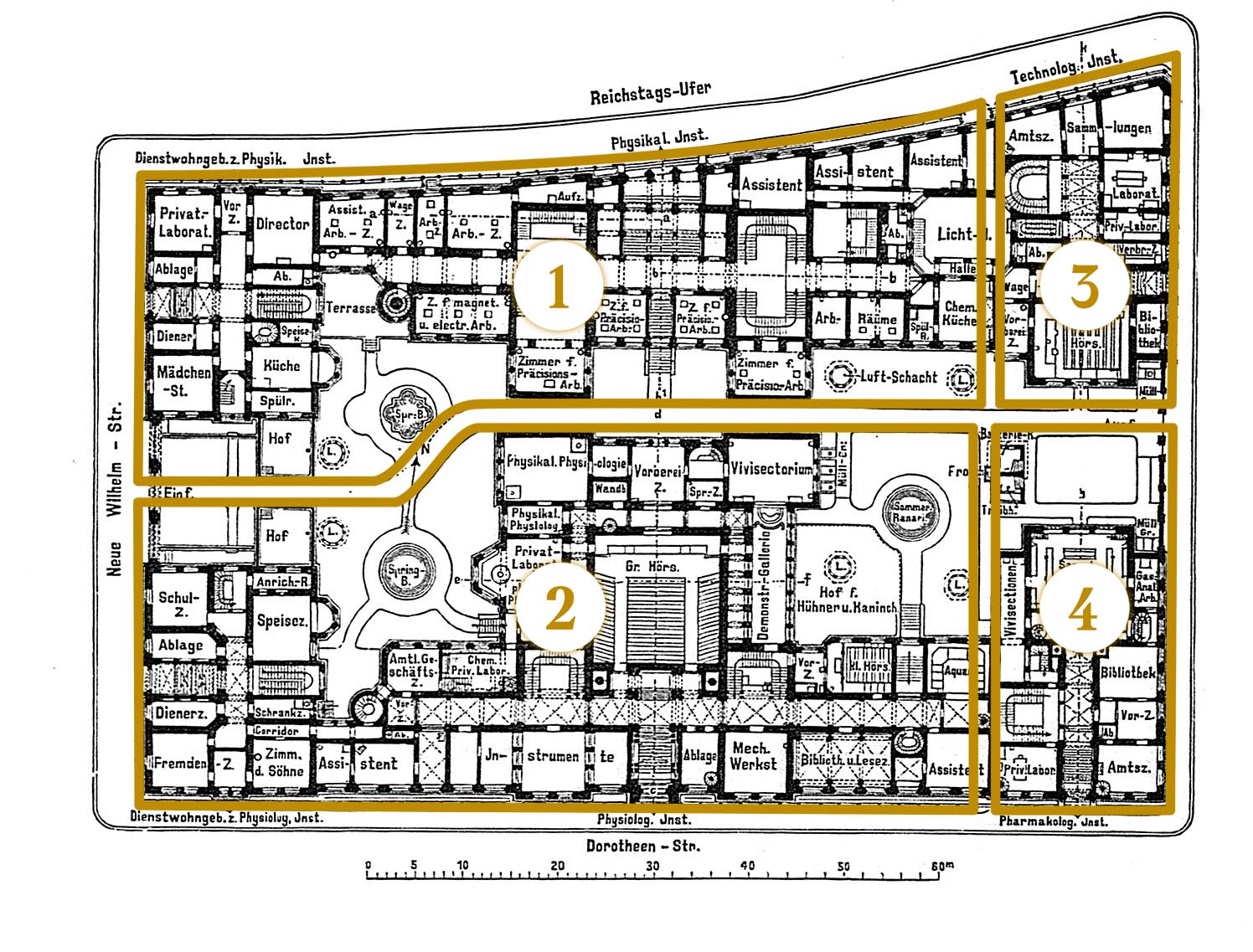

A scientific city quarter (Dorotheenstraße) An entire street block was occupied by Europe's largest institute building in 1878. With a view of the Spree and Reichstag, Hermann von Helmholtz, Max Planck and Walther Nernst conducted research here...

… while Emil Du Bois-Reymond and Robert Koch worked and lectured, resp., in the block at the back, which still exists.

Four institutes in one building As if the university wanted to resist fragmentation into individual disciplines, the natural sciences were outsourced together and made possible what we now call interdisciplinarity. The scientific success should not fail to materialize. -

1 Physics 1878

2 Physiology 1878

3 Physical Chemistry 1883

4 Pharmacology 1883

Conflicts with City Development

Already when the scientific institutes of Berlin’s University were built (1873-1878), the scientists had to fight that a light rail line planned in front of their institute would not make their sensitive experiments impossible. Star observations, chemical experiments, physical and physiological measurements – were these still possible in the metropolis?

The city railroad problem Thanks to Helmholtz and Du Bois-Reymond, the city railway makes a double curve between the main station and Friedrichstraße station. But shortly after their death in 1897, Siemens & Halske again proposed to pass an under pavement railway directly in front of the Institute of Physics… -

The city railroad problem Thanks to Helmholtz and Du Bois-Reymond, the city railway makes a double curve between the main station and Friedrichstraße station. But shortly after their death in 1897, Siemens & Halske again proposed to pass an under pavement railway directly in front of the Institute of Physics… -

From Representation to Functionality

“… whether it would be appropriate to erect the monumental buildings that are customary at unusually high cost, or whether one should rather be content with very simple utility buildings (for example in the form of a barrack) …”

Handbuch der Architektur, 1905

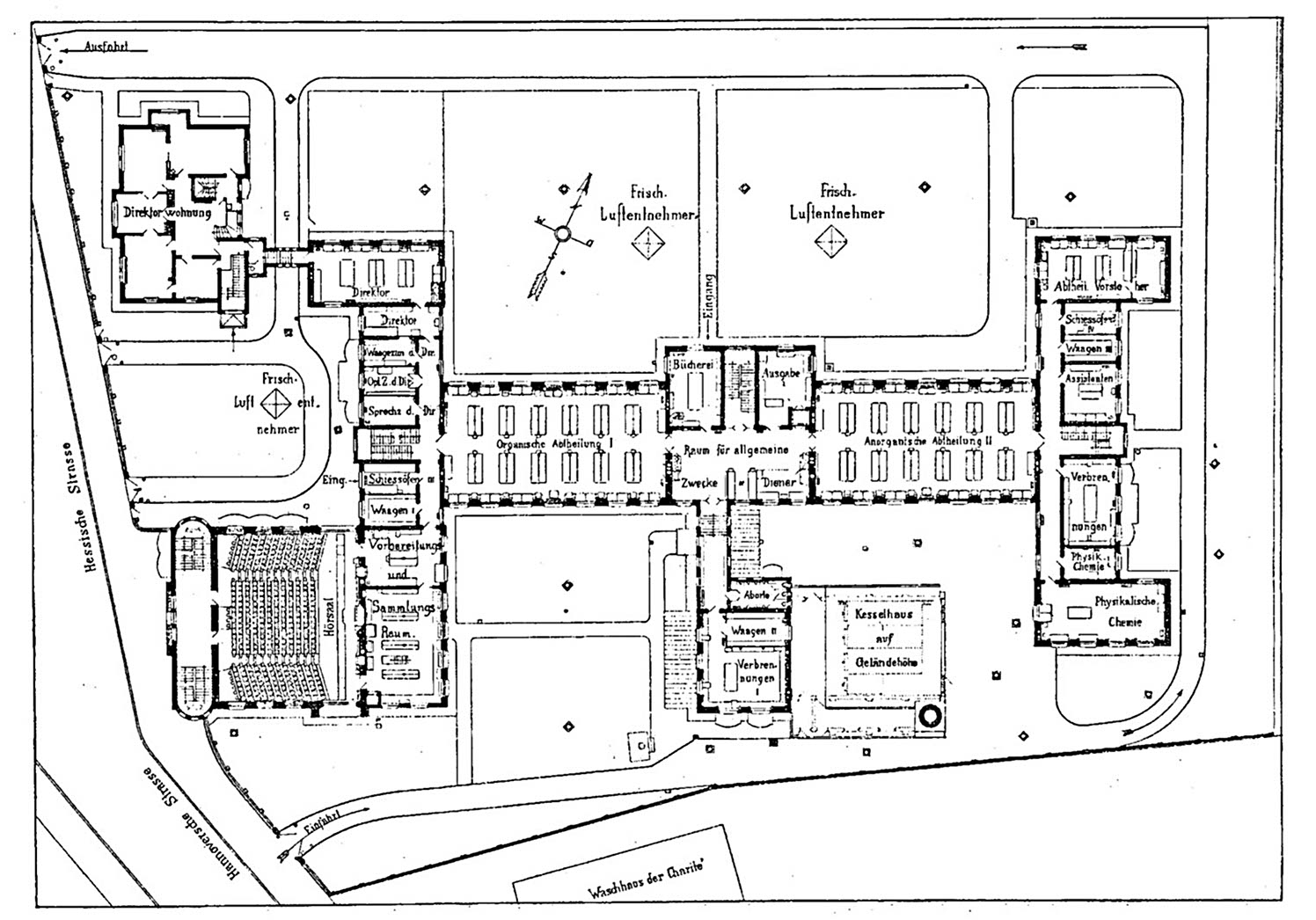

The new Chemical Institute of the University of Berlin The new Chemical Institute of the University of Berlin, which was rather unpretentious from the outside, the new institute was “unsurpassed in diversity and richness of its work equipment by any similar institute in the world”, asso Emil Fischer announced at the opening in July 1900.

The craggy ensemble of buildings hardly shows up from the street and is only directed at the requirements of research.-

Functional institute architecture of the Chemistry Institute by Emil Fischer, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1902.

3 Unity and Relocating

3 Unity and Relocating

Unity of Science – Unity of Location?

In the growing European metropolis of Berlin in the late 19th century, universities tried to open up further inner-city spaces that were urgently needed for institutes, laboratories, but also for the collections. In close connection with urban development, they were able to acquire areas previously used for industrial purposes. Above all, however, the vision of outsourcing the entire university to the periphery of the city became the focus of all considerations. This vision should have long-term effects – in completely different political circumstances.

Lindenstraße:

Schinkel’s Observatory (1835) The observatory of the academy from 1710 was one of the few scientific institutions in the immediate vicinity of the university and was used by it after its foundation. It was not until 1889 that the observatory was officially transferred from the academy to the university, but this was the new one near Hallesches Tor, built on cabinet order and completed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel in 1835. One reason for the relocation was the better observation conditions outside the poor city air.

Lindenstraße:

Today, little reminds us of this science location, to which further institutes belonged. As the town grew, the conditions deteriorated and in 1913 the observatory was demolished, the land sold and the funds raised were used to build a new one in Babelsberg Castle Park.

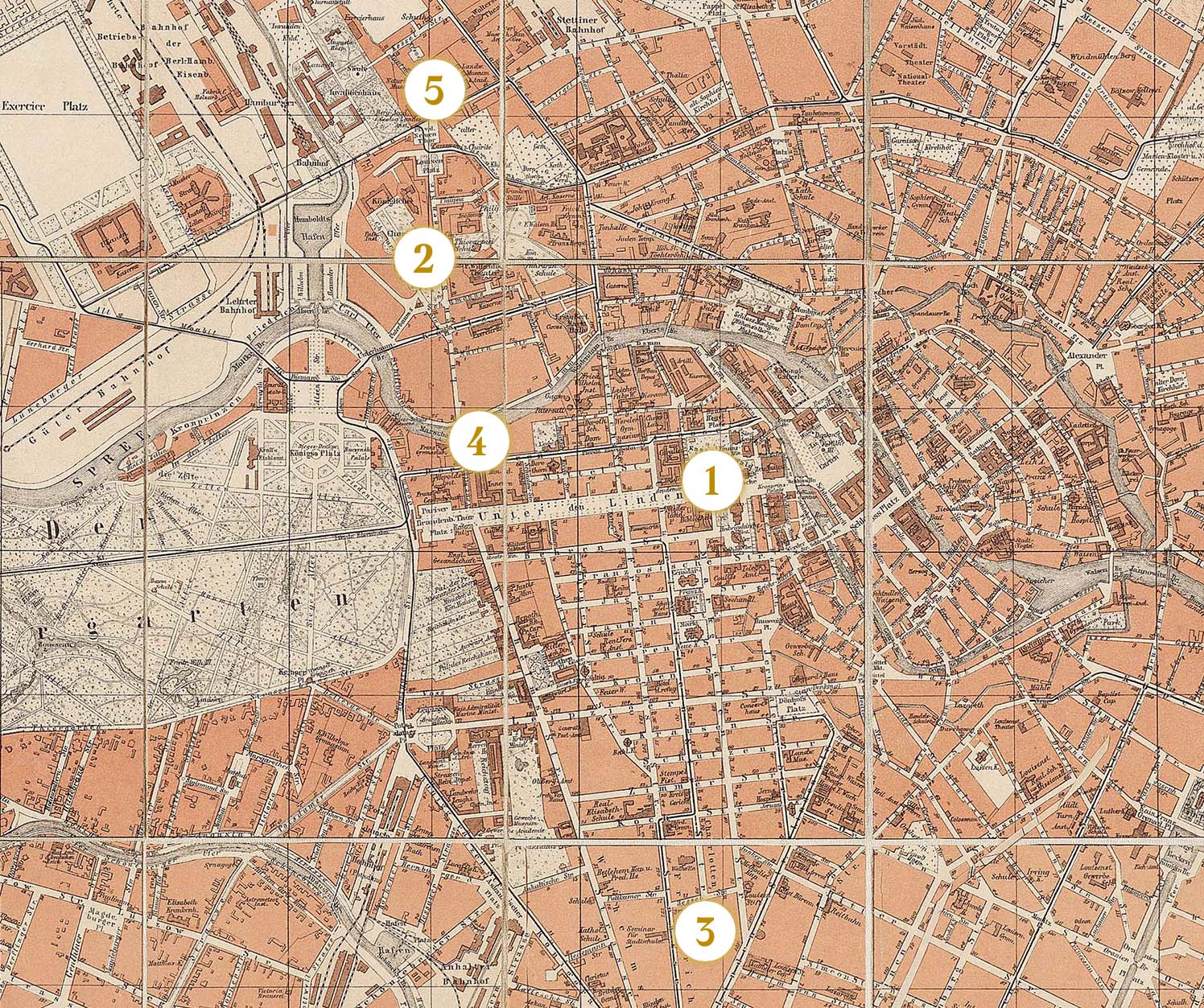

Invalidenstraße

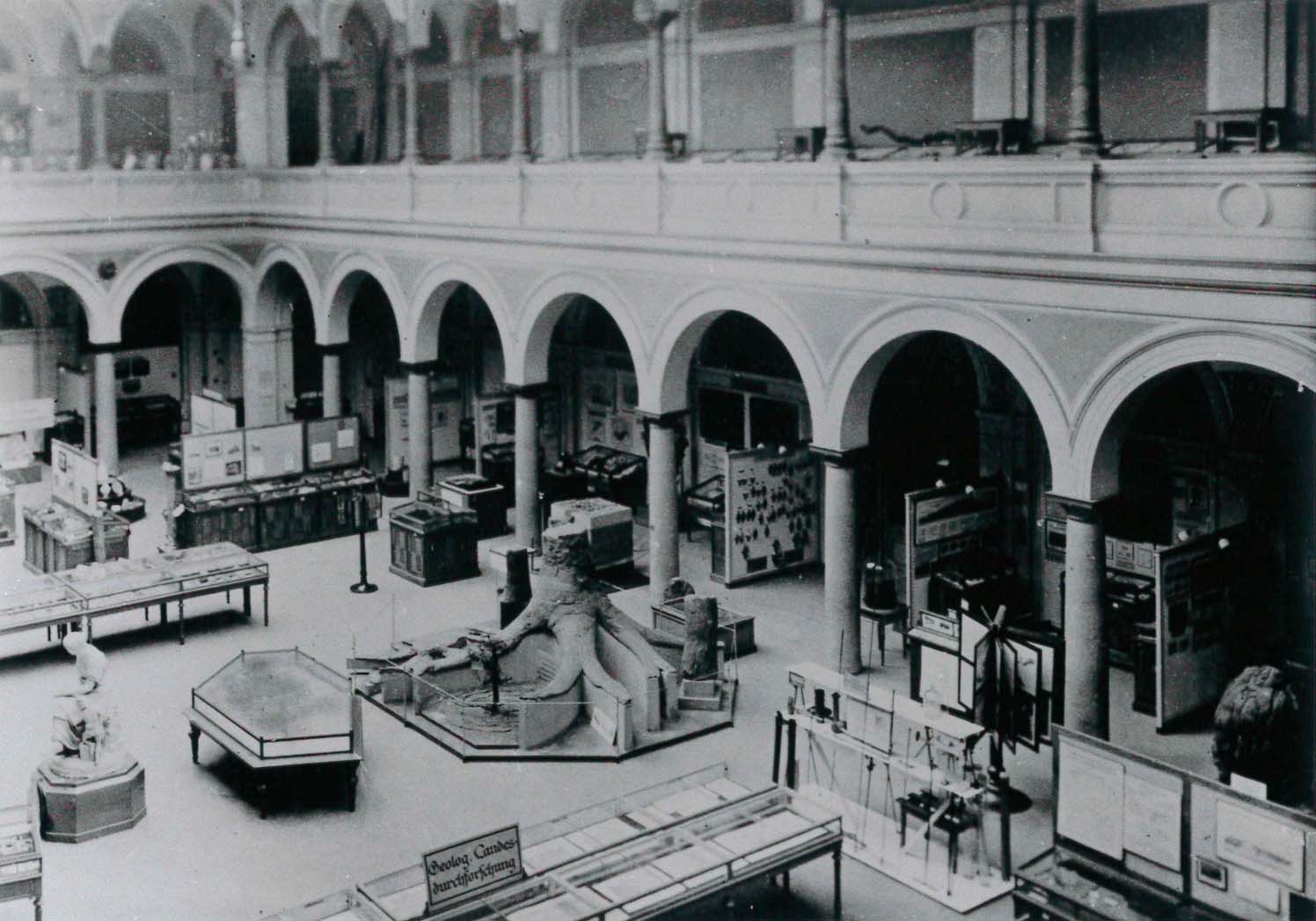

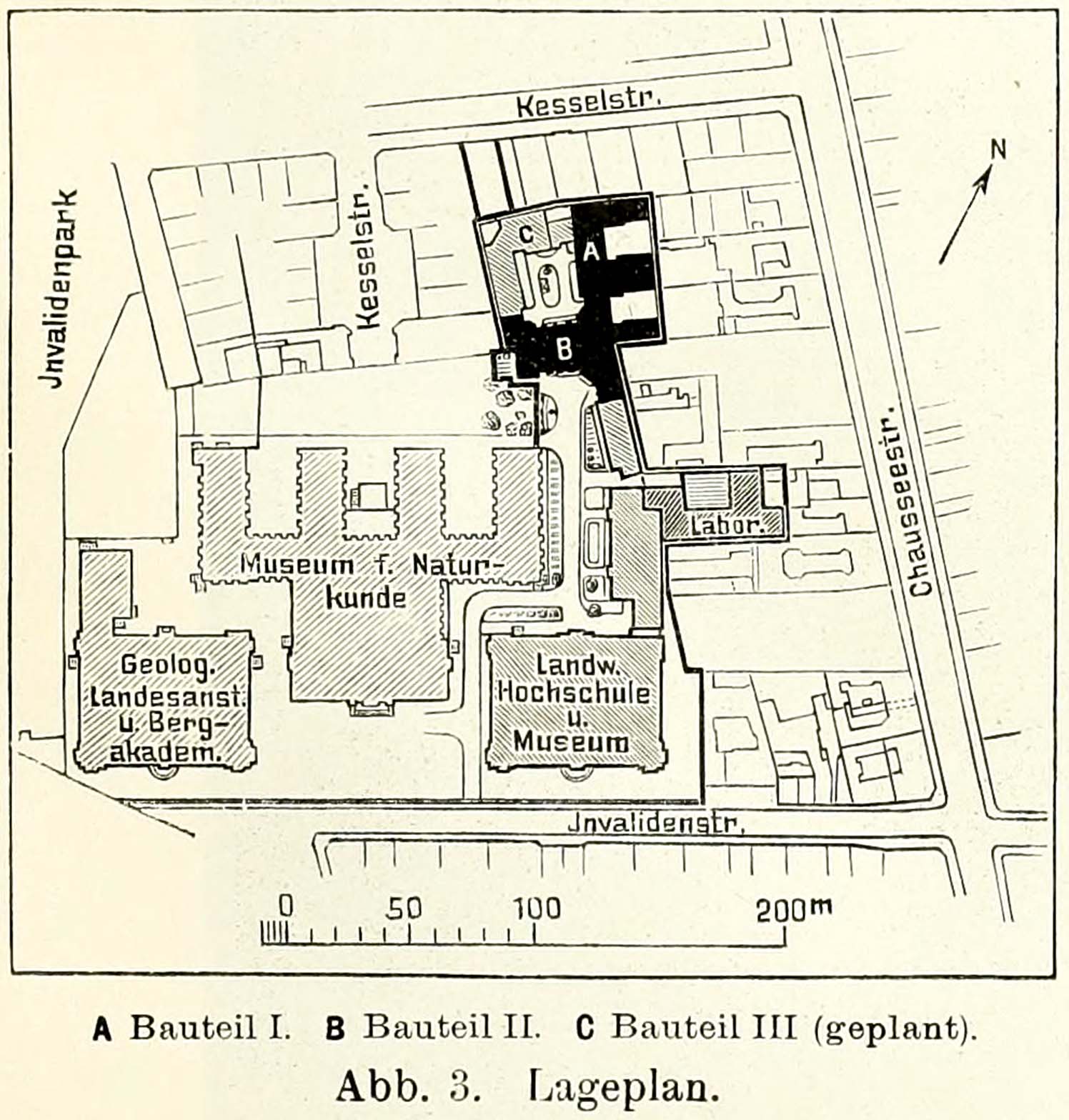

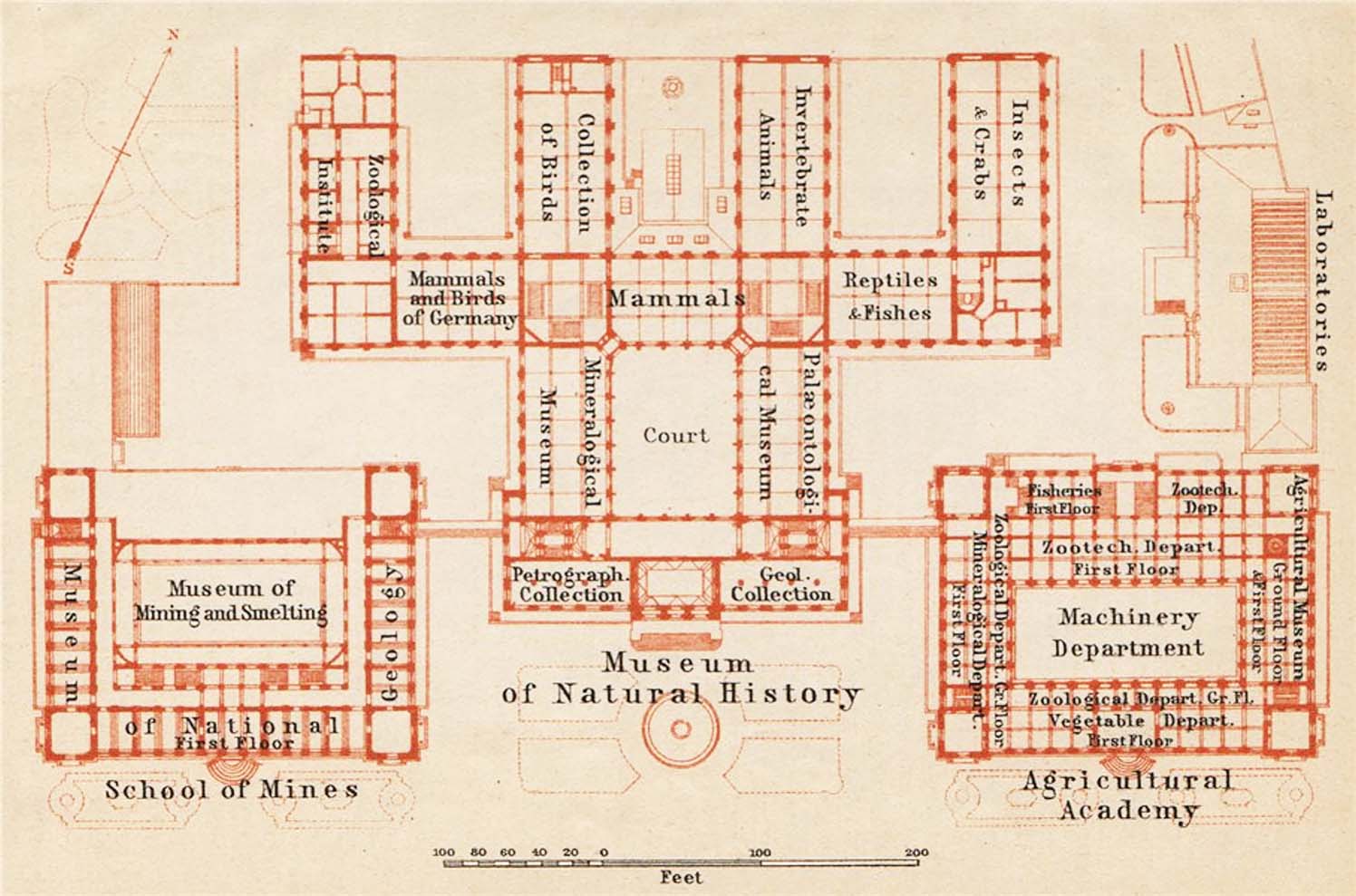

The area in front of the New Gate in northern Berlin was popularly called Fireland because iron foundries were based here. When these were relocated in 1872, museums and colleges were established at this place. In addition to the Mining Academy (with the State Geological Office) and the Agricultural Academy, it was especially the Museum of Natural History that was to bring relief for the university.

Museum of Natural History 1889In the spirit of a teaching of direct observation, the Unter den Linden building was overwhelmed by the growing zoological, mineralogical and other natural history collections. Now in 1889, a great many exhibits moved into the Museum of Natrual History institutions and made it possible to reuse the main building after reconstruction.

Mining Academy 1878

The Mining Academy also had a scientific exhibition in the atrium (as did the Agricultural College).

The Invalidenstraße locationThe three scientific institutions form an architectural unit and served as the nucleus for a science and museum complex on Invalidenstrasse. With an architecture a little less showing off than the Technical University, they were part of a hierarchy of the Empire, which is also reflected in the design of the buildings.

Travel guides such as the Baedeker show the connection between the educational and exhibition functions of the three institutions. The Museum of Natural History also had strictly scientific collections in addition to the public display collections.

From University to Museum

The Giant Triton, a sea snail shell, shown here, like thousands of other shells, minerals or vertebrates, moved in 1888 to the new Museum of Natural History, which was not built on the Museum Island, as originally intended, but on Invalidenstraße. The related institutes had also moved with the objects and the museum remained part of the Humboldt University until 2009.

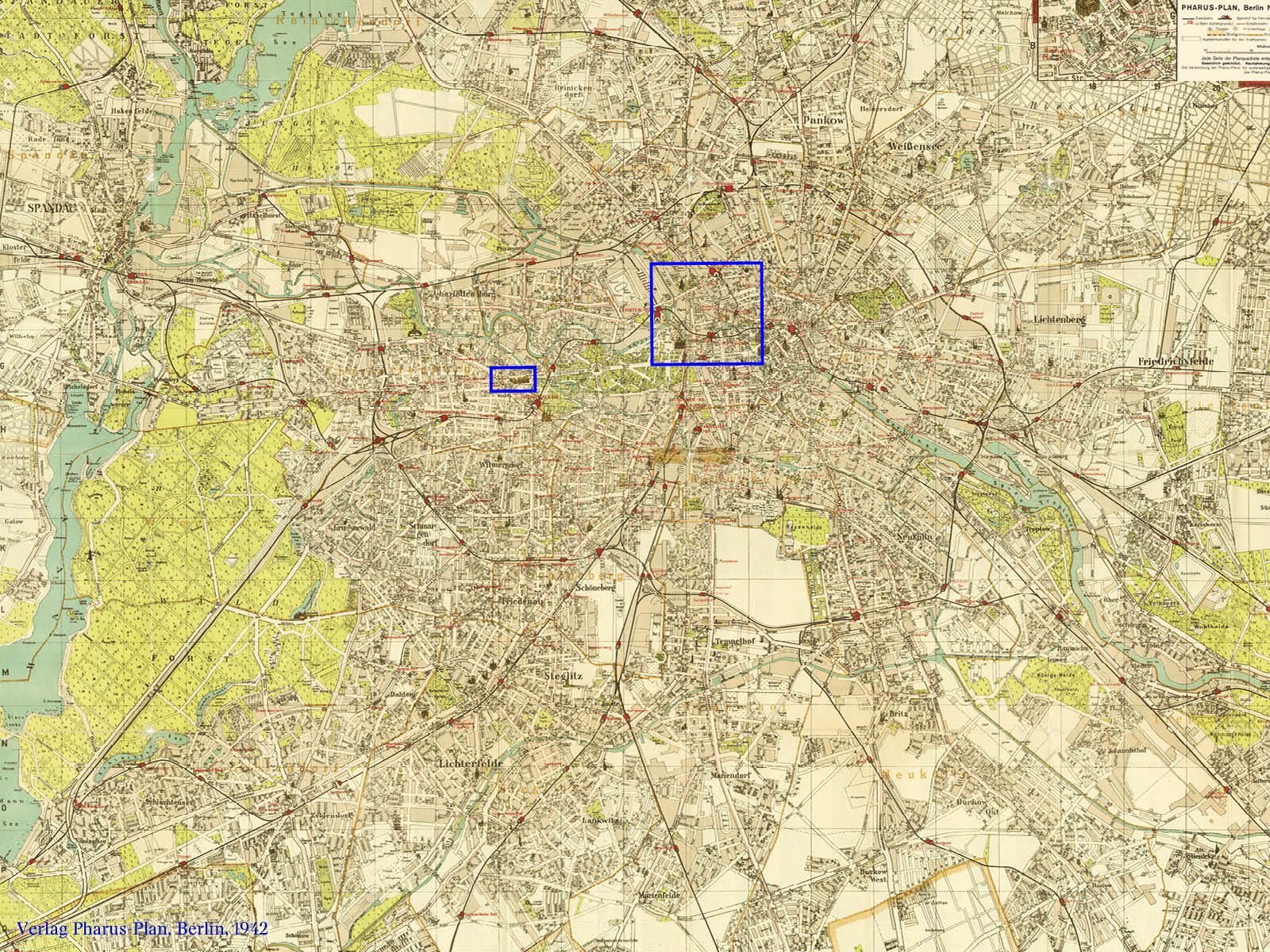

The Dream of the Campus University

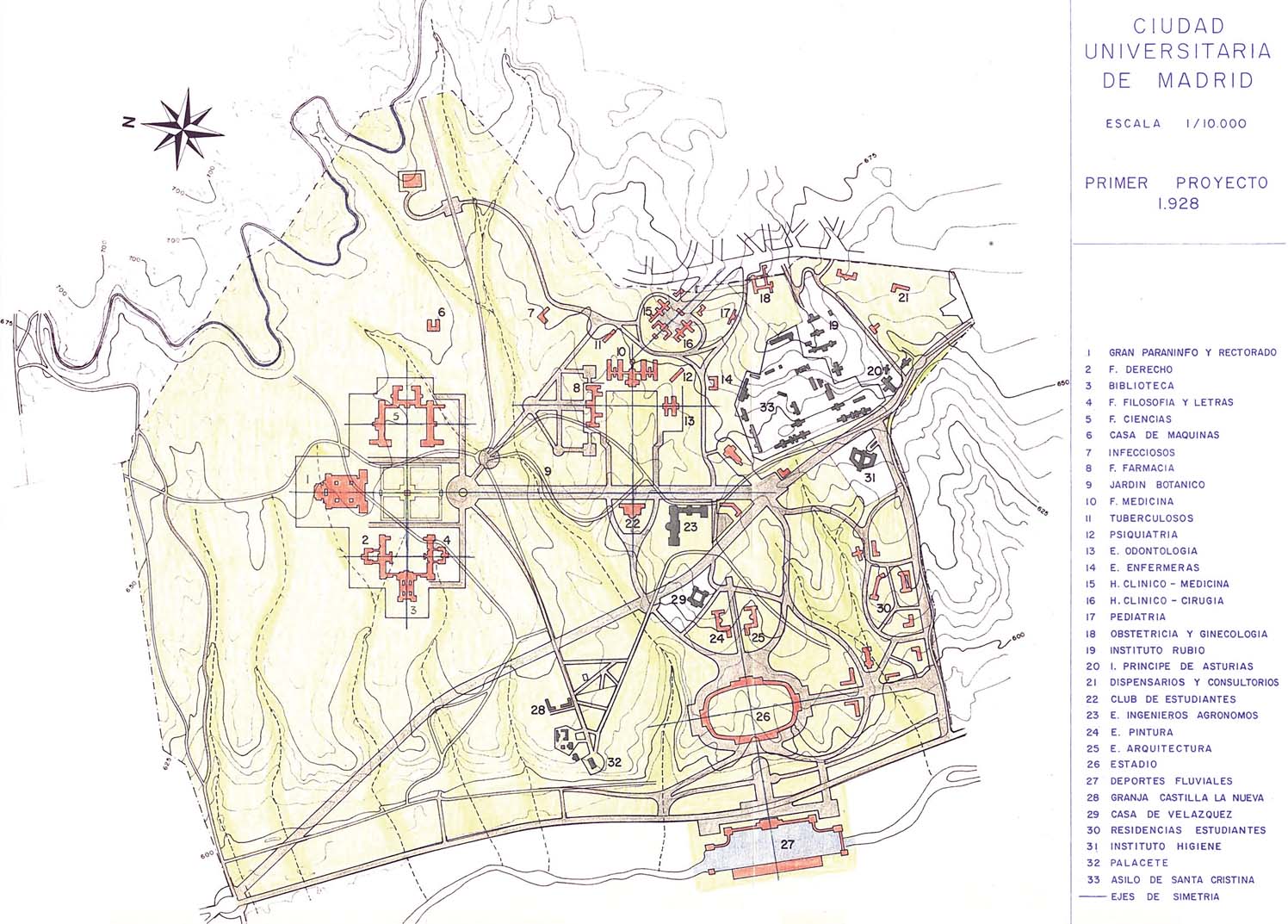

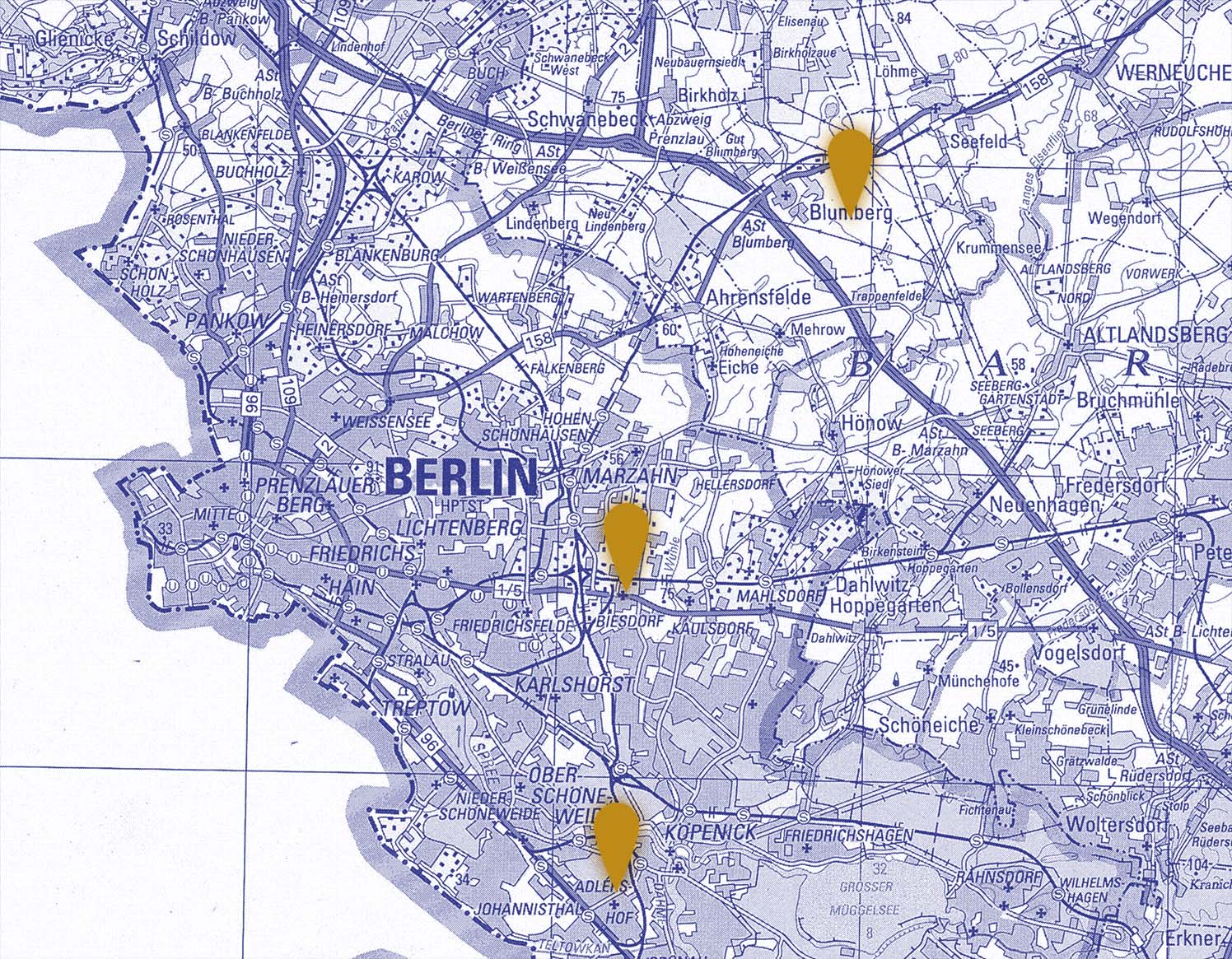

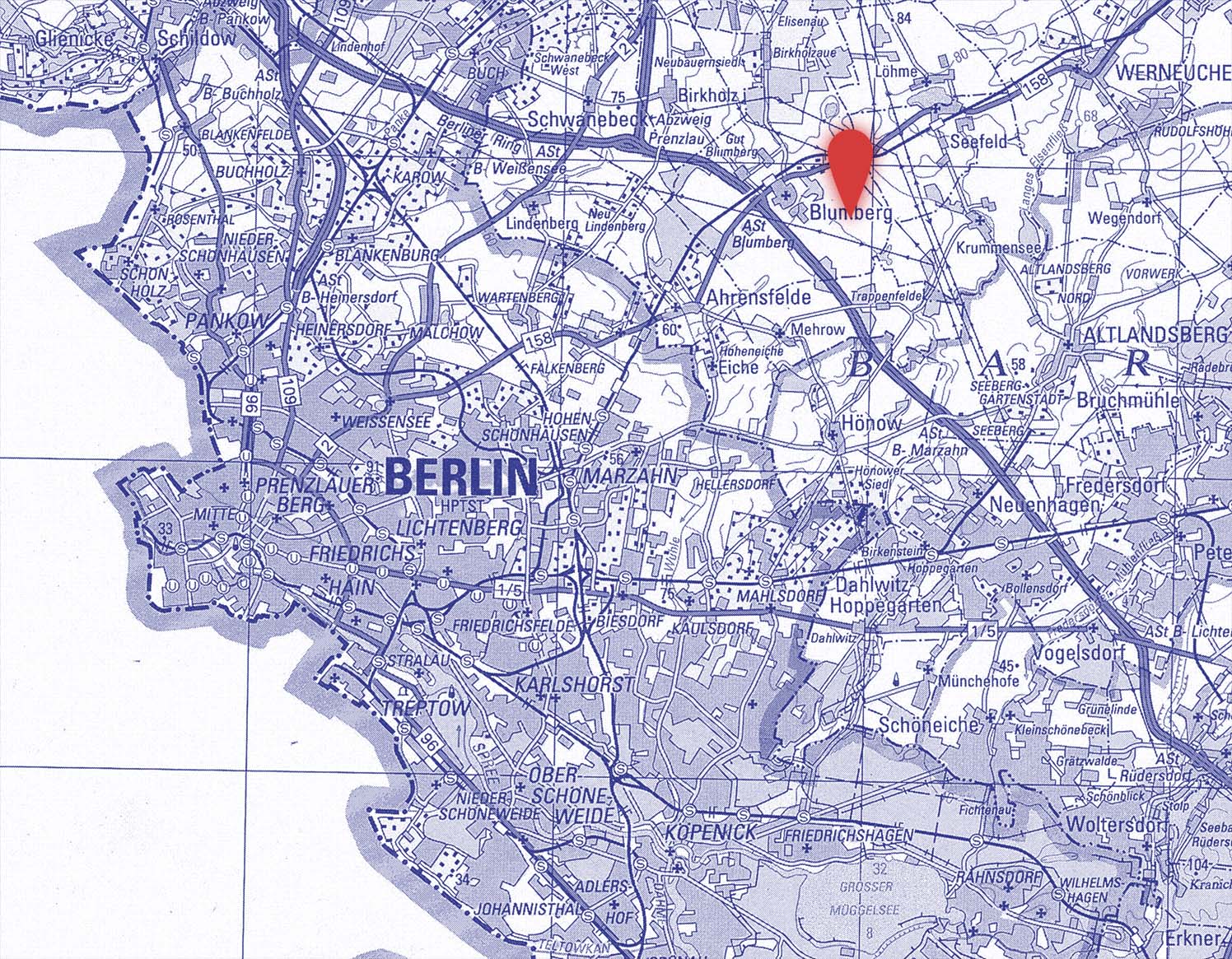

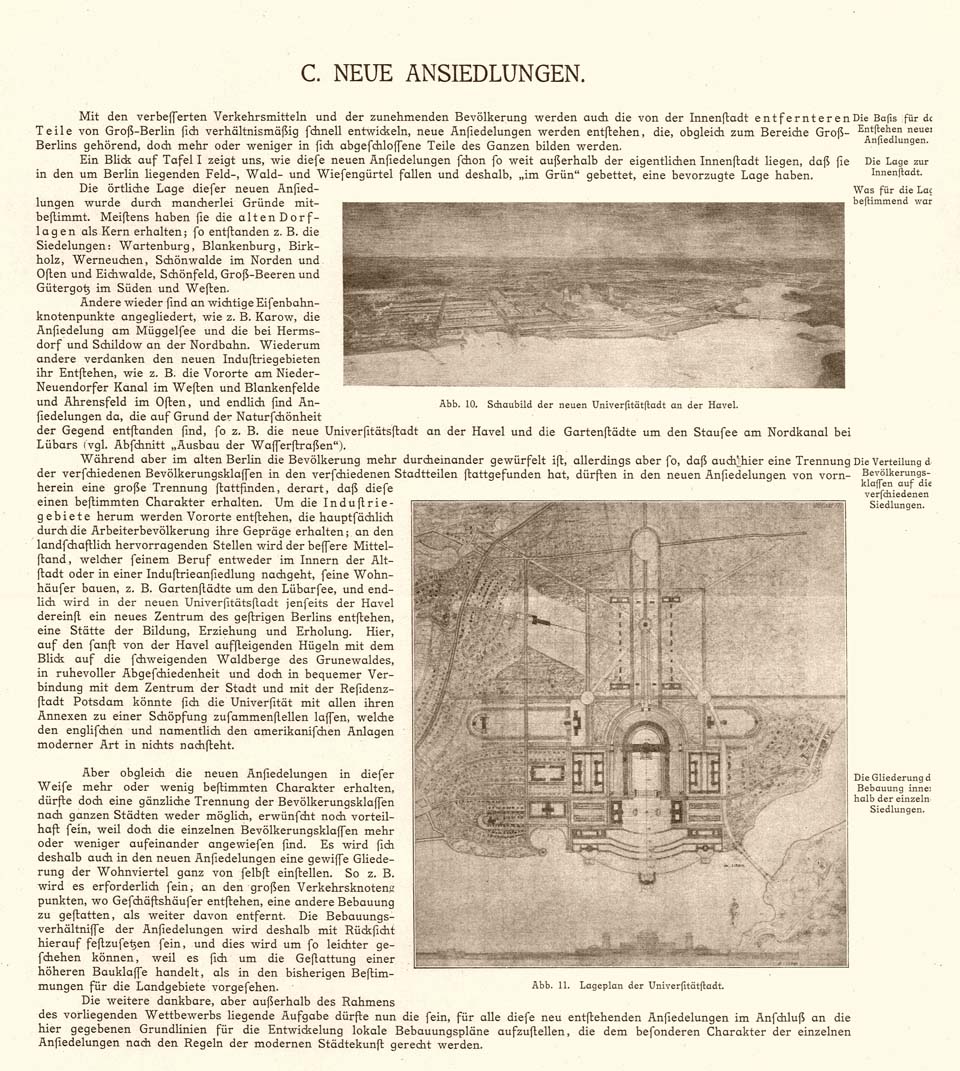

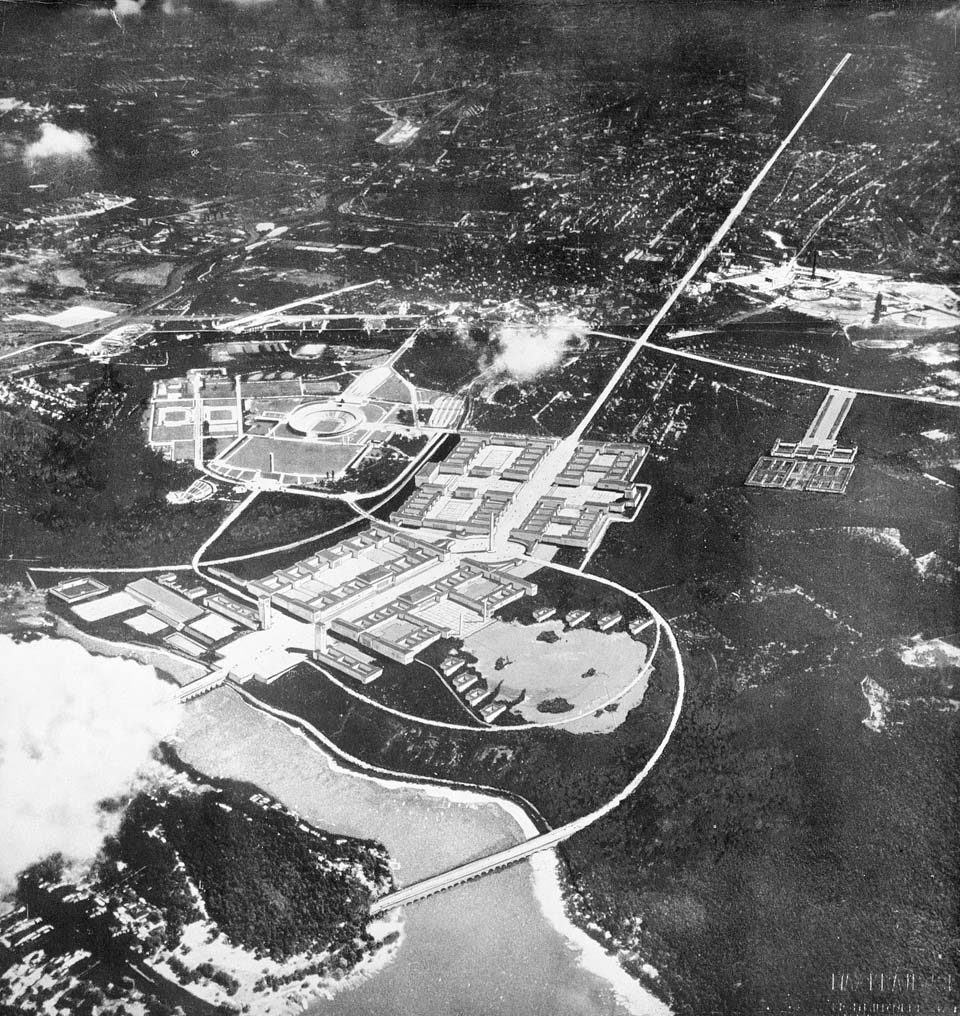

The idea of relocating the entire Berlin university(s) from the city centre is a recurring one, e.g., 1873 and in the 1890 to the periphery, around 1902 to Dahlem, 1910 and 1925 to the Havel, 1939 to the Heerstraße, 1960 to Blumberg... Apparently the dream of a grand educational architecture on a university campus could always inspire, but never be realized in Berlin.

The Greater Berlin Competition 1910

The design by Havestadt & Contag in 1910 shows the vision of a campus university with monumental buildings north of the Havel, which is connected to the city centre by a railway bridge. In 1925 the architecture critic Karl Scheffler would promote it again.

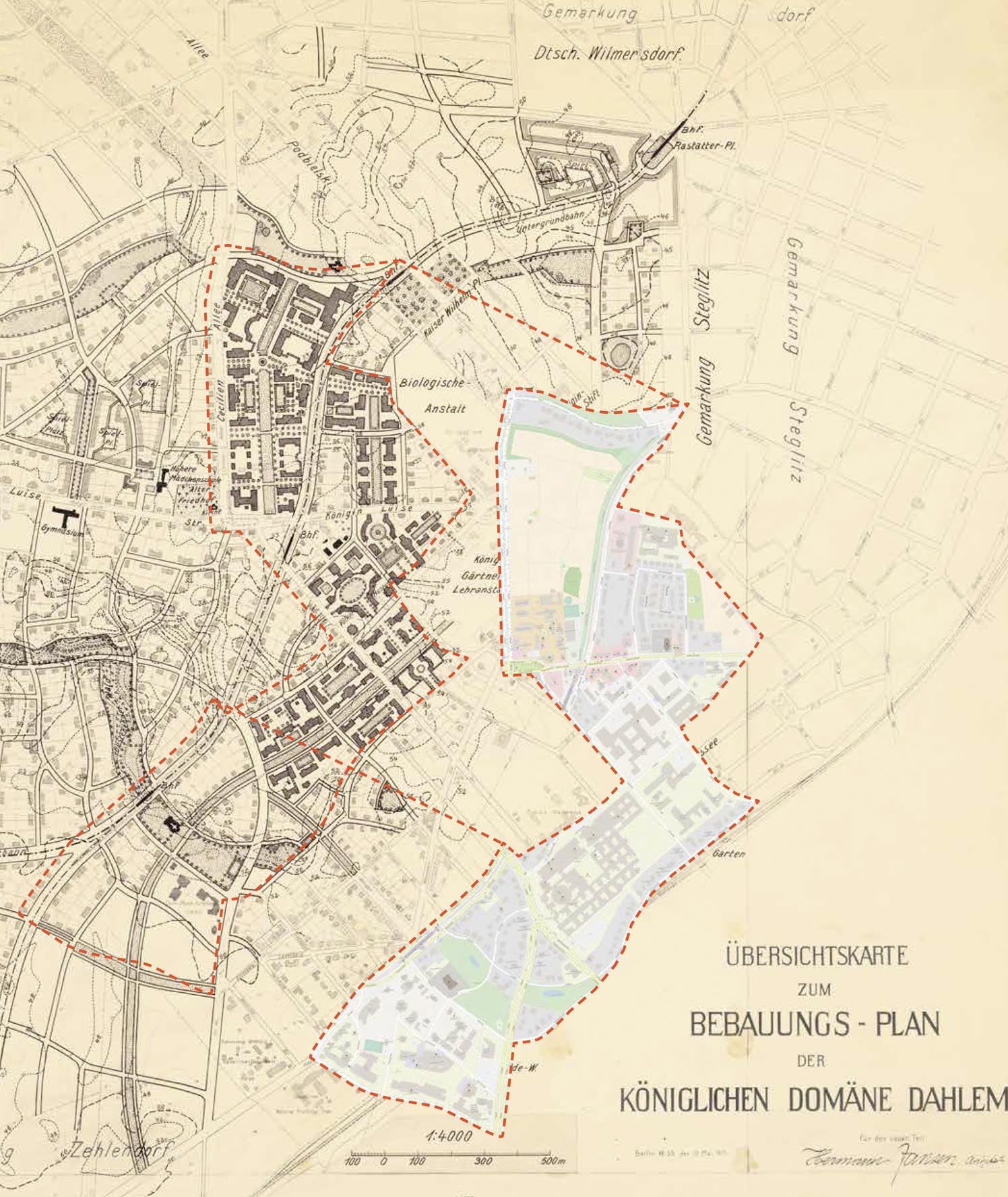

Dahlem

In the 1890s, Friedrich Althoff in the Prussian Ministry of Culture was no longer able to attract some professors to Berlin because there were no rooms and building sites for attractive institutes. When the Dahlem Estate was divided in 1901, he tried to reserve at least 250 acre for science. When his plan to move the entire university to Dahlem failed, attempts were made to use the “reserves” at least for the natural sciences and for museums and archives.

Dahlem

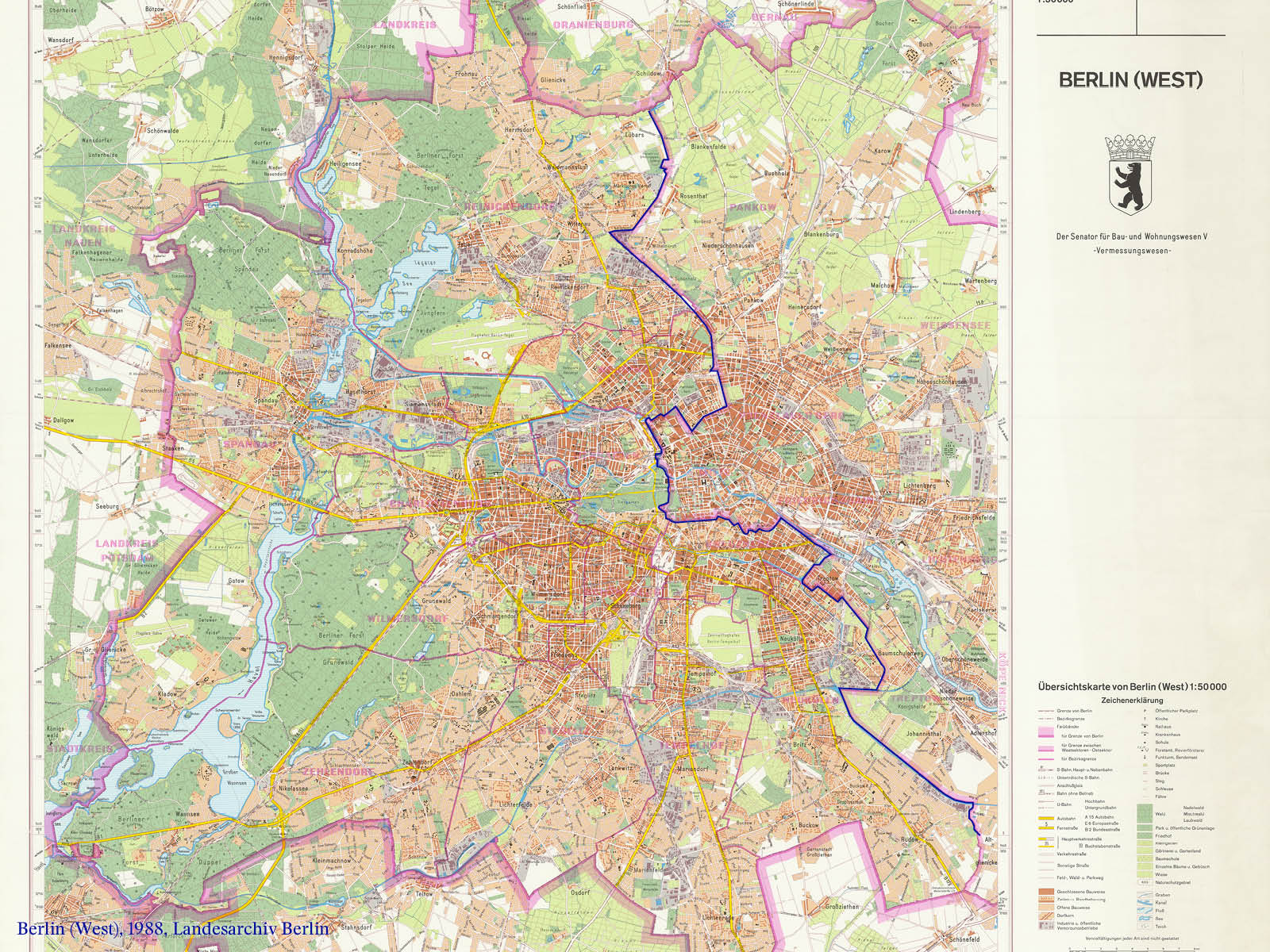

It was not until the end of the sixties that Freie Universität was to settle into the outlines of the turn of the century.

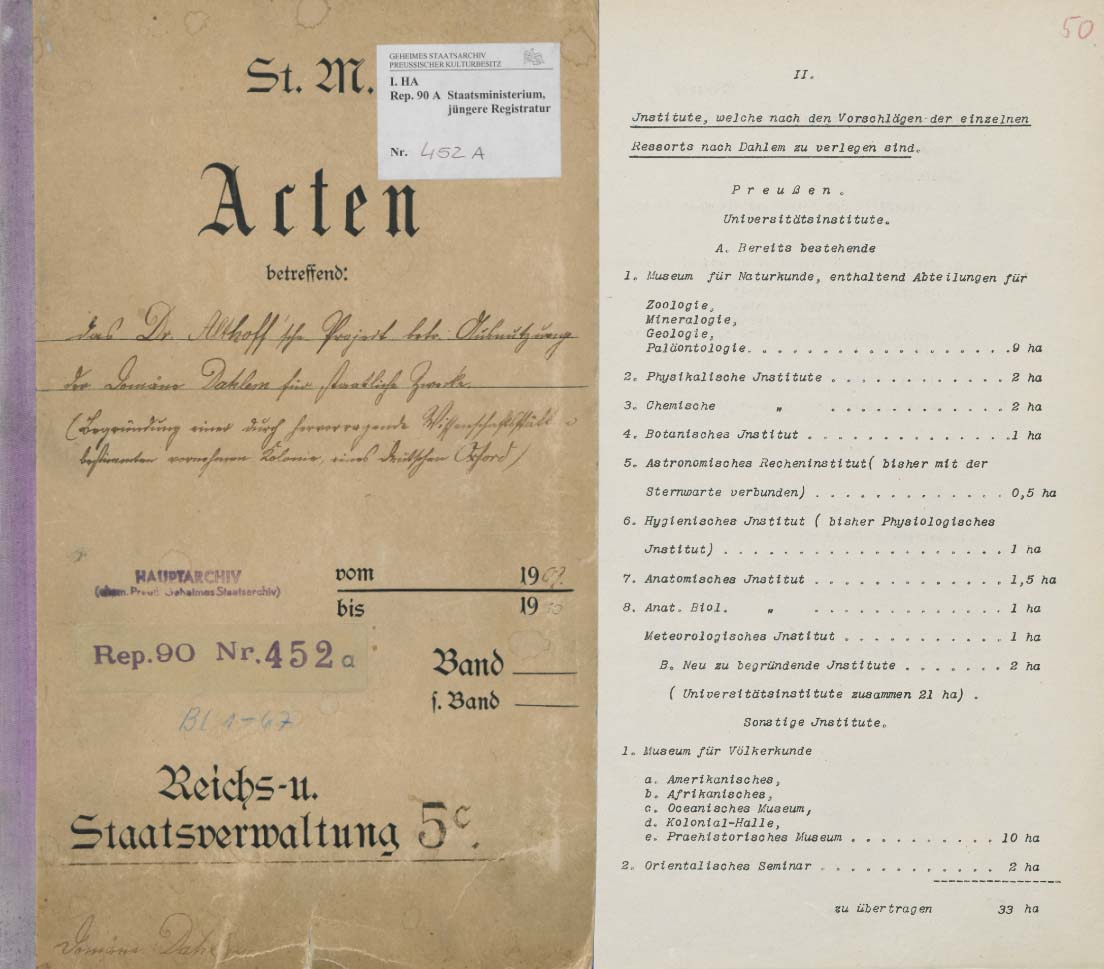

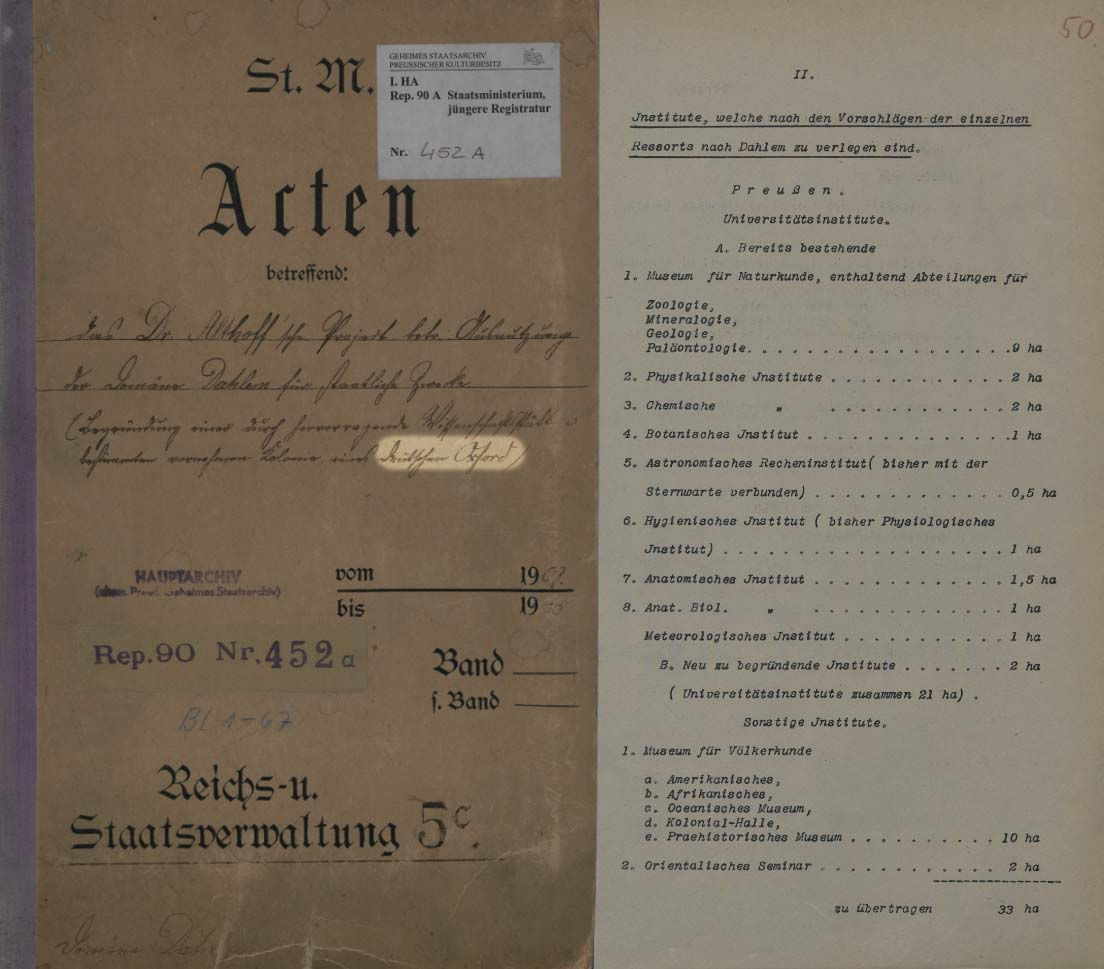

A “German oxford”?

The extensive files on the expansion of Dahlem as a new scientific location fill volumes. Here one also finds the phrase, which goes back to Friedrich Althoff, of the “establishment of a distinguished colony determined by outstanding scientific sites, a German Oxford” (in brackets on the cover of the file). The idea was not to imitate British college universities in Oxford or Cambridge, but rather to use the words “distinguished” and “Oxford” to express what probably is meant by “excellence” today.

A “German oxford”?

The extensive files on the expansion of Dahlem as a new scientific location fill volumes. Here one also finds the phrase, which goes back to Friedrich Althoff, of the “establishment of a distinguished colony determined by outstanding scientific sites, a German Oxford” (in brackets on the cover of the file). The idea was not to imitate British college universities in Oxford or Cambridge, but rather to use the words “distinguished” and “Oxford” to express what probably is meant by “excellence” today.

4 Neo-Monumentalism on Campus

4 Neo-Monumentalism

The model of US American campus universities was also received in Europe. It gained new popularity after the First World War. In the outskirts of major European cities, the functional requirements could be implemented in comparable plants. Large areas made it possible to combine all faculties in one location. The old idea of the unity of science in the university was once again expressed here.

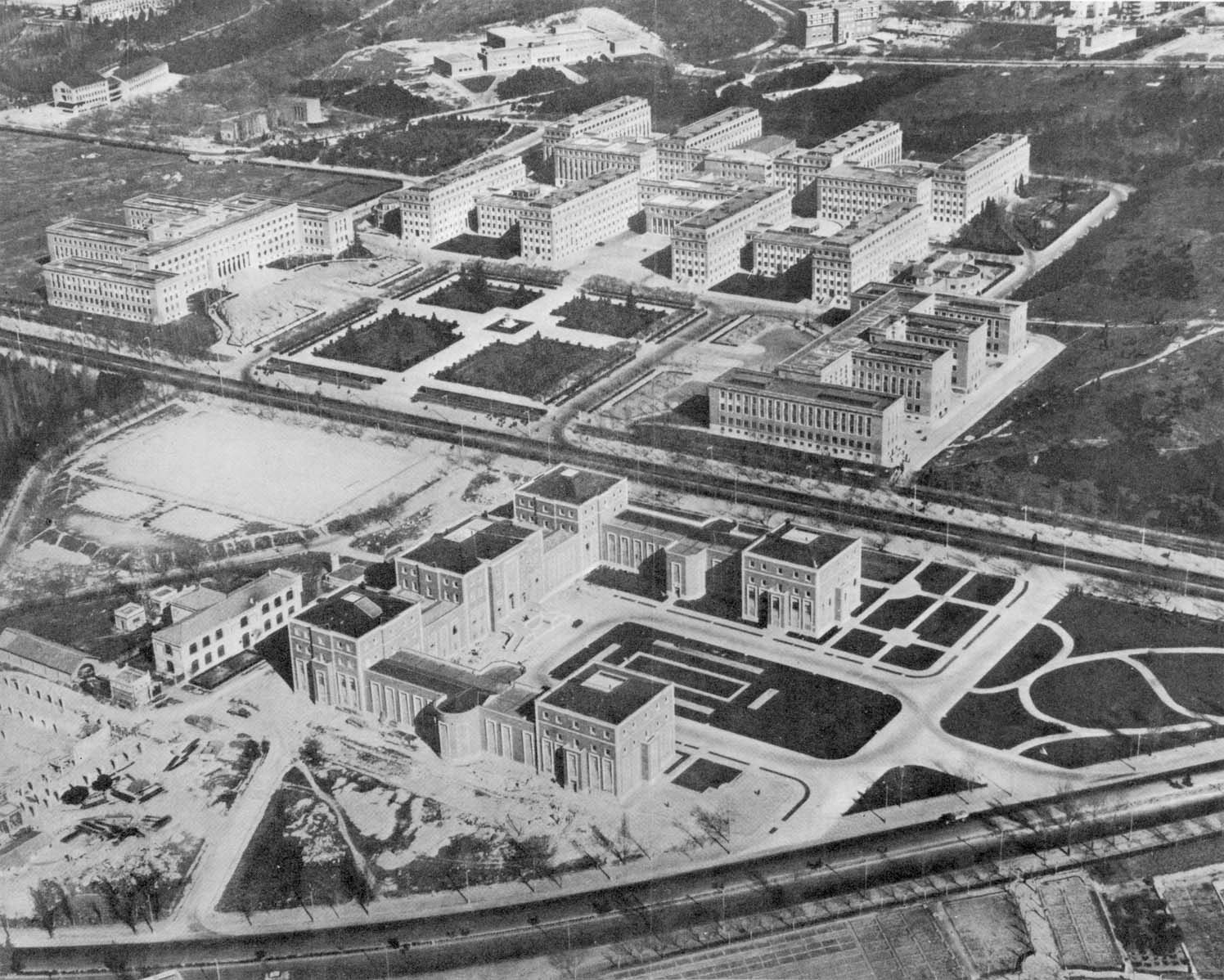

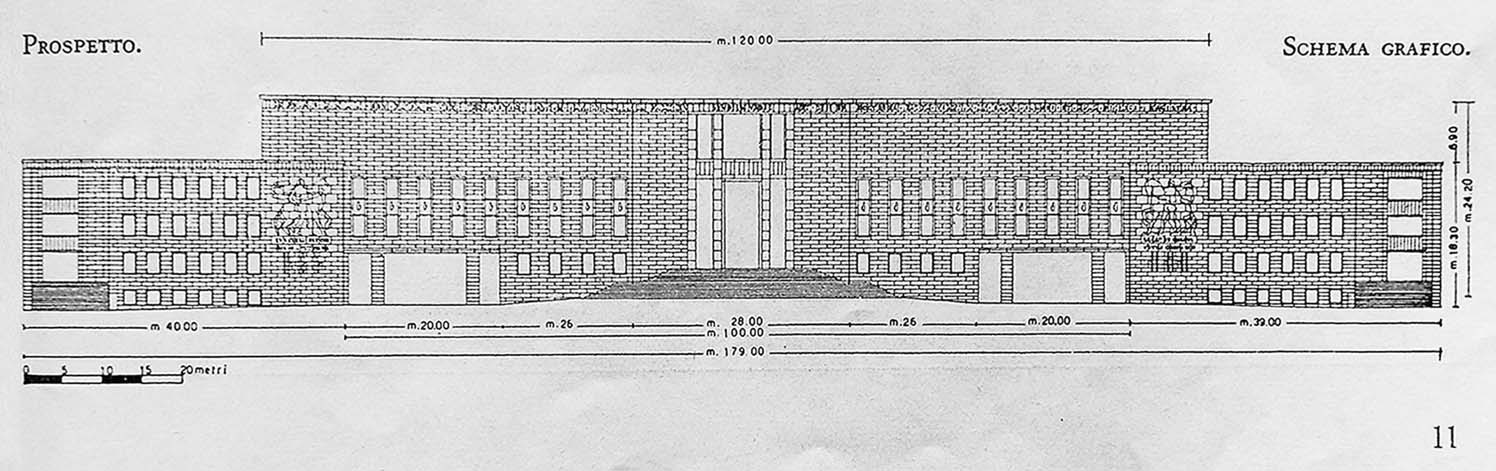

Models in Madrid and Rome

NS Campus Plans in Berlin

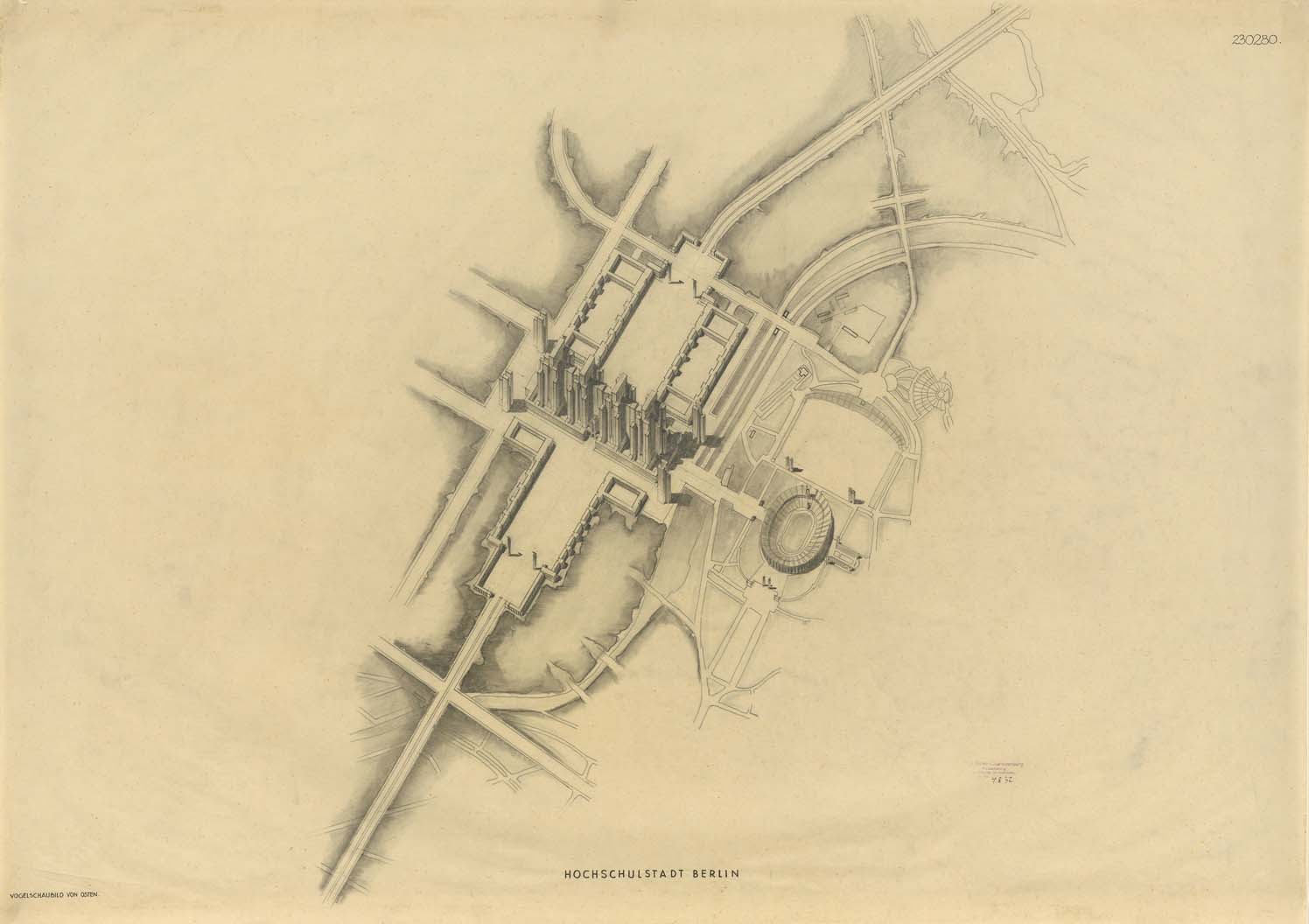

More than in any other country, the sciences were instrumentalized and their organization centralized in National Socialist Germany. In Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer’s plans, the construction of a monumental university town, starting in 1937, formed a central element in the radical transformation of Berlin. South of the Olympic Stadium, a huge complex was to be built as a gateway to the Reichshauptstadt Germania on the brutally beaten east-west axis through the city. The new university building in Rome was also used as a model for Berlin’s “University Town”.

NS University Town

Almost all architectural designs that were submitted for the architectural competition were characterized by an “oversize without scale” (Wolfgang Schäche). Here an example by Otto Kohtz in which the Berlin Olympic Stadium looks small on the right hand side.

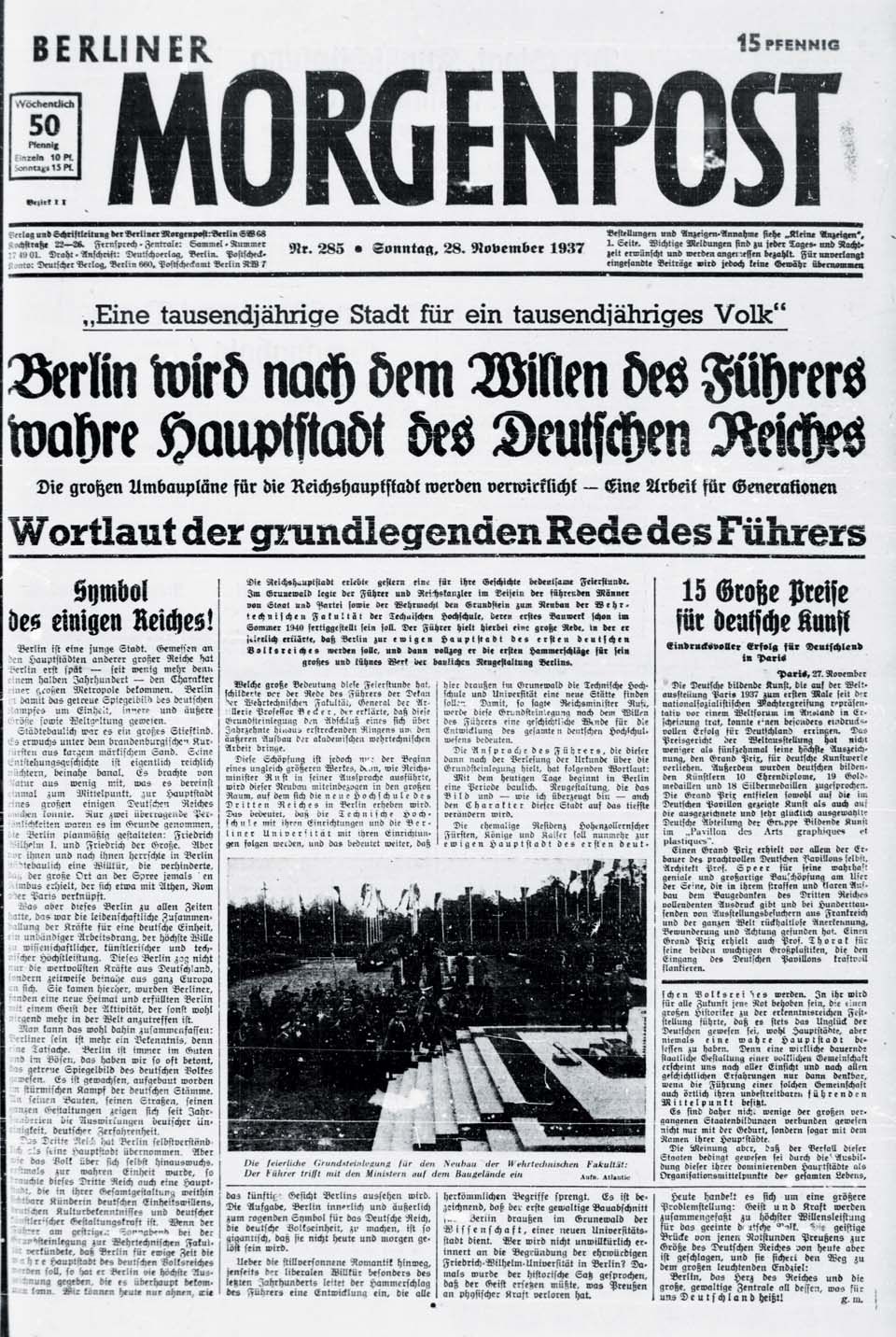

Prelude to a millenarian city?

In his speech at the laying of the foundation stone of the Faculty of Defence Technology in 1937, Adolf Hitler emphasised the importance of the project of the “university city” for the project of a complete transformation of Berlin: “Today marks the beginning of a period of structural redesign in Berlin that will change the image and [...will profoundly change the character of this city.” The Faculty of Defence Technology was to be the prelude for the construction of a “thousand-year-old city” and in this context the propagandistic function of a “monument[s] [...] of German culture, German knowledge and German power”.

Completion was planned for 1950. All work was stopped, however, at the beginning of the war in 1939.

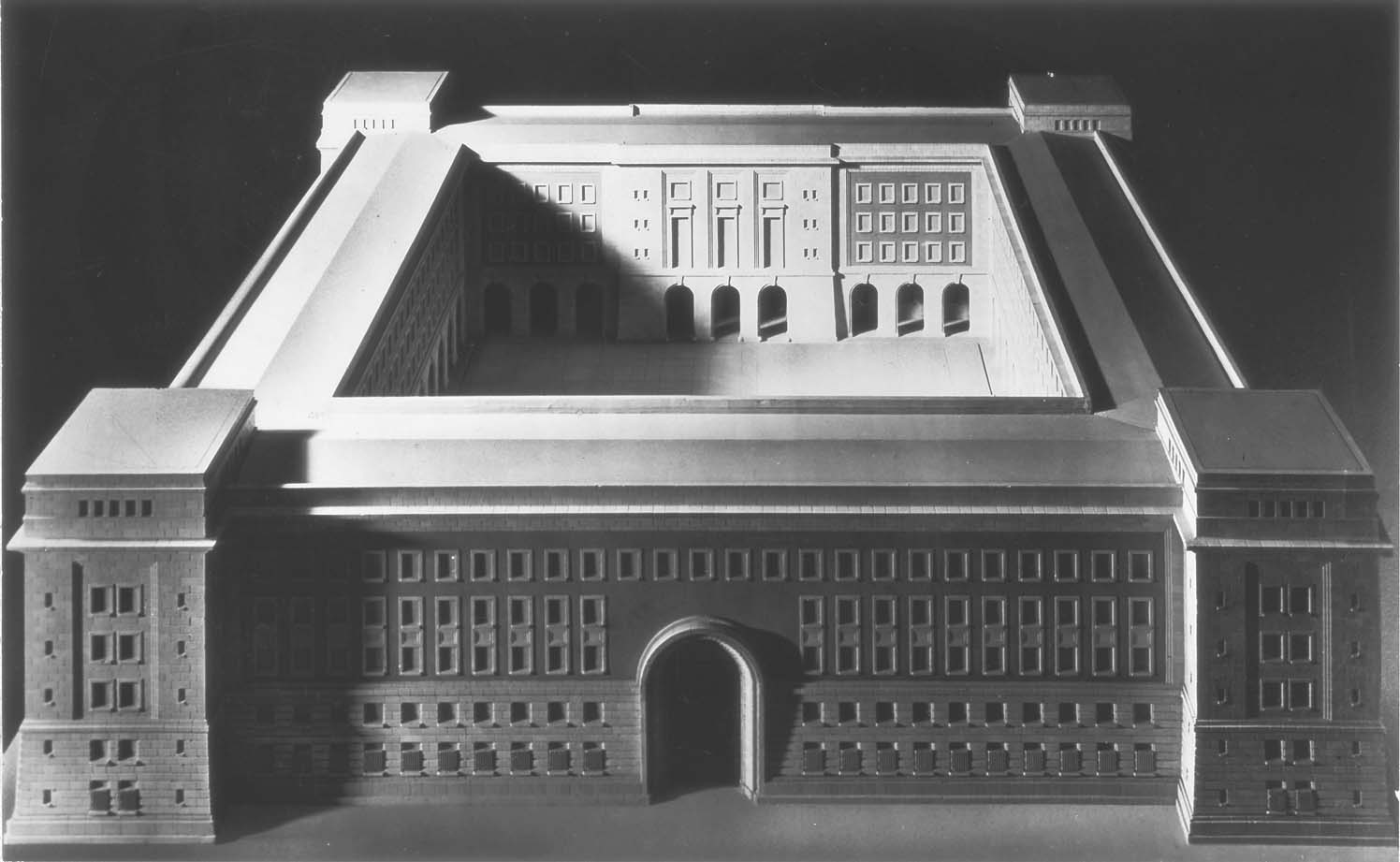

The Faculty for Defense Technology

The first project was the construction of the Faculty of Defence Technology in 1937, which expressed the primacy of war-important research. Only the shell of the main building, a design by Hans Malwitz, was completed.

Contemporaries were already made aware of the dimensions of the completed building (here Main Building). Due to the war, construction had to be stopped.

The shell of the building was destroyed in the war. Today, the remains of the ruins lie under the Teufelsberg in the Grunewald.

The Technical University in National Socialism

On the occasion of Mussolini's visit in 1937, the main building of the Technical College, which was situated on the same road axis as the planned university city, was given a parade ground in front of it. There is little left of that today.

The street lights, part of Albert Speer's decoration programme for the east-west axis, today’s Straße des 17. Juni, still bear witness to the Nazi past.

5 Re- | New Construction

5 Re- | New Construction

Berlin’s University without Priority

“Workers and peasant children to the university!” This was demanded by an appeal in the newspaper in January 1946 at the time of the reopening. For this purpose, the buildings on Unter den Linden were only temporarily repaired. New buildings for science were out of the question, because priority was given to residential and social buildings to enable a new class to study at all. There were new scientific buildings and locations for the academy, which was to monopolize top-level research according to the Soviet model.

There were several attempts to find new locations for the HU. Adlershof with its wind tunnels, the former aeronautical research institute and the new academy institutes was the obvious choice for the for the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences. But this was vetoed in 1960 by the Ministry of State Security, which ran a guard regiment there. Only after reunification were these plans implemented in a new form.

“Humboldt University”

The Berlin University was not renamed after Marx and Engels, but after Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt in 1949. First of all, the facades were restored: The renewed portal with the words “Humboldt Universität” in October 1951. Socialism was reflected in the Marx quotation on the stairs (May 1953) and in the leaded windows of the new auditorium (1962).

The new Technical University

At the Technical University, newly founded in 1946, they knew what they did not want (any longer). The young architect of the TU Willy Kreuer was already involved in the America Memorial Library, which was meant to be a symbol of freedom of expression. Now he had the task of designing a building for “Coal, Iron and Steel” that broke with imperial and Nazi traditions. In addition, the whole Ernst-Reuter-Platz was to become a “symbol of free Berlin”.

Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

Willy’s Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (1959), is built in a new reinforced concrete skeleton construction, and has columns clad in aluminum, that clamp blue glass windows. The square structured building appears to float above the ground.

Ernst-Reuter-Platz

Inspired by Corbusier’s ideas of the “vertical city”, Bernhard Hermkes developed an urban planning solution to the demand for “democracy as a builder”. An open development without emphasis on axes and street stars was combined with a free flow of traffic and understood as a response of the free West to the Stalinallee and Strausberger Platz.

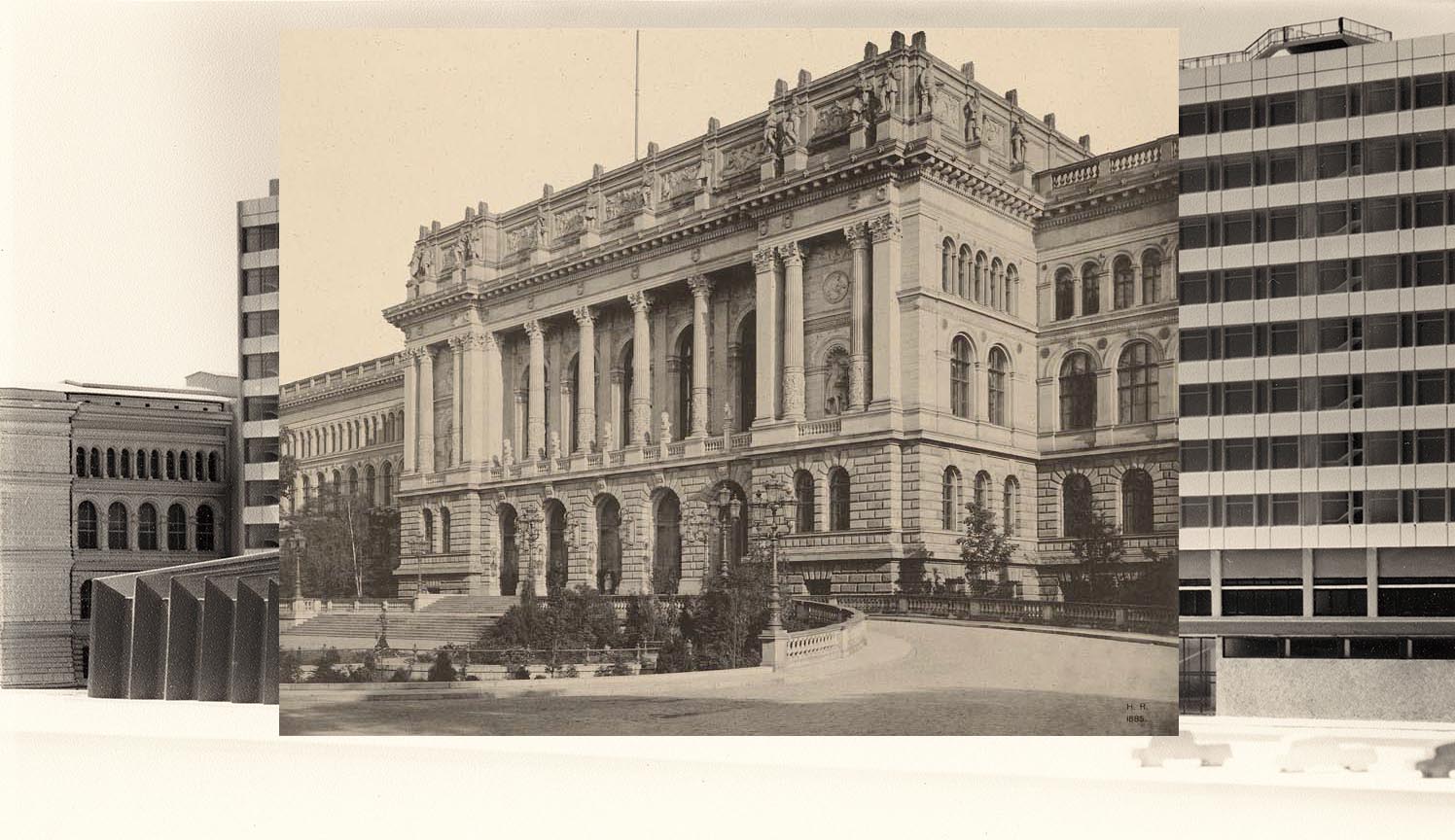

TU Main Building

Between 1960 and 1965 the architects Kurt Dübbers and Karl-Heinz Schwennicke replaced the front section of the main building, which had been largely destroyed in the war, with a ten-storey high-rise and re-clad the side wings. This radically changed the impression: the old building was made completely obscured and a purely functional architecture was realized.

TU Main Building

Between 1960 and 1965 the architects Kurt Dübbers and Karl-Heinz Schwennicke replaced the front section of the main building, which had been largely destroyed in the war, with a ten-storey high-rise and re-clad the side wings. This radically changed the impression: the old building was made completely obscured and a purely functional architecture was realized.

The Architecture of Freedom

“The Free University is ... the living testimony to the struggle for intellectual and cultural freedom... a protest against the oppression of the intellect by the steppe.”

(Rector Edwin Redslob, in the commentary to the construction competition of 1951)

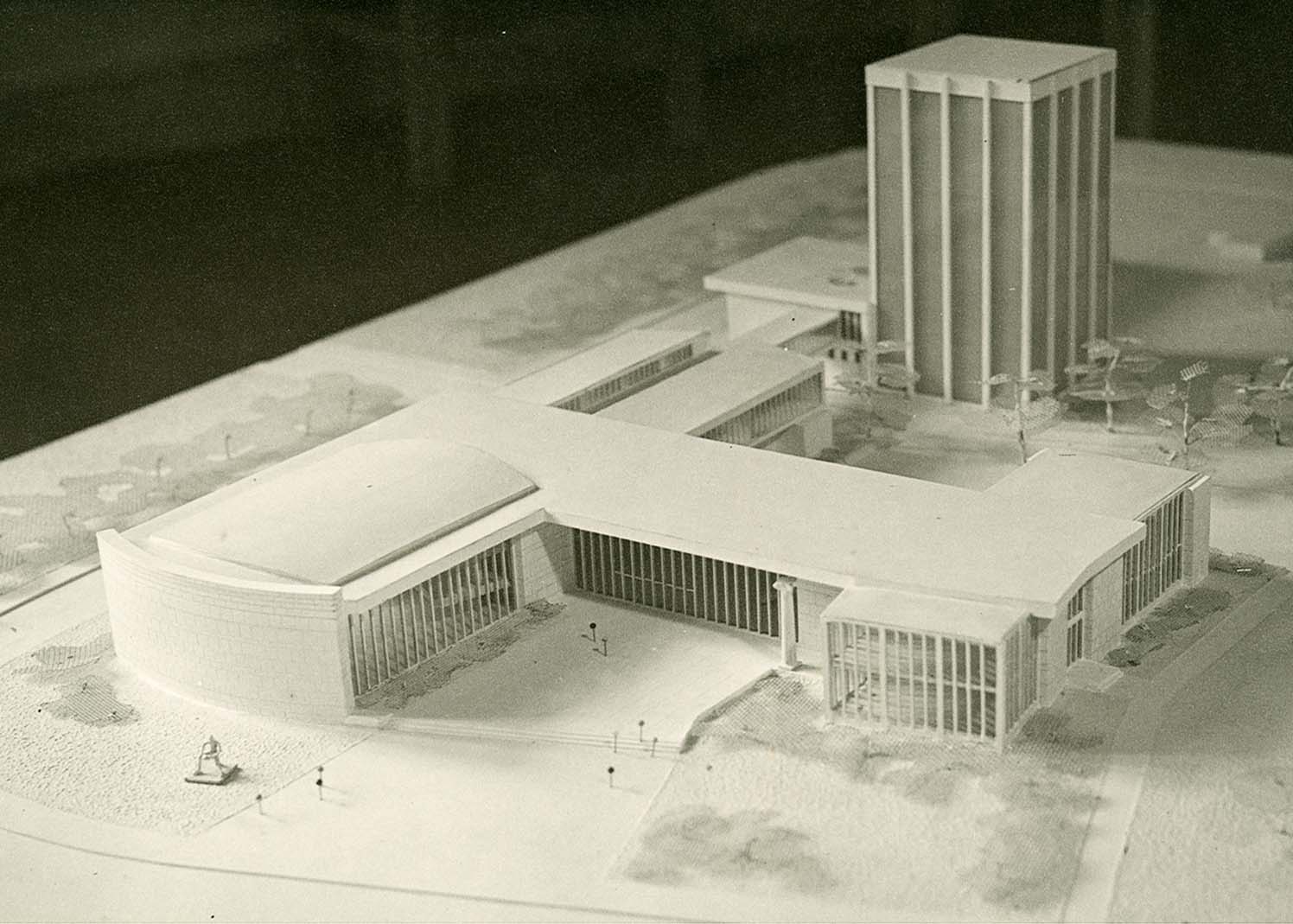

Henry-Ford-Bau

The architectural prelude for a new free university was the Henry Ford Building in 1954 - after the classic-modern canteen, which had already been opened in the previous year. The complex, financed by the American Ford Foundation, combined the Audimax and other lecture halls with a library. Bright, open, transparent and spacious, American and German stylistic elements were combined, for example by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Bauhaus.

The Henry Ford Building was the first main building of Freie Universität. Franz-Heinrich Sobotka and Gustav Müller designed an open and inviting ensemble of buildings, which creates in the view of the founding rector Edwin Redslob an analogy to the courtyard of honor of the University of Unter den Linden is created: Th e Freie Universität carries on the spirit of research of the old university, now “lost” to the GDR, in West Berlin.

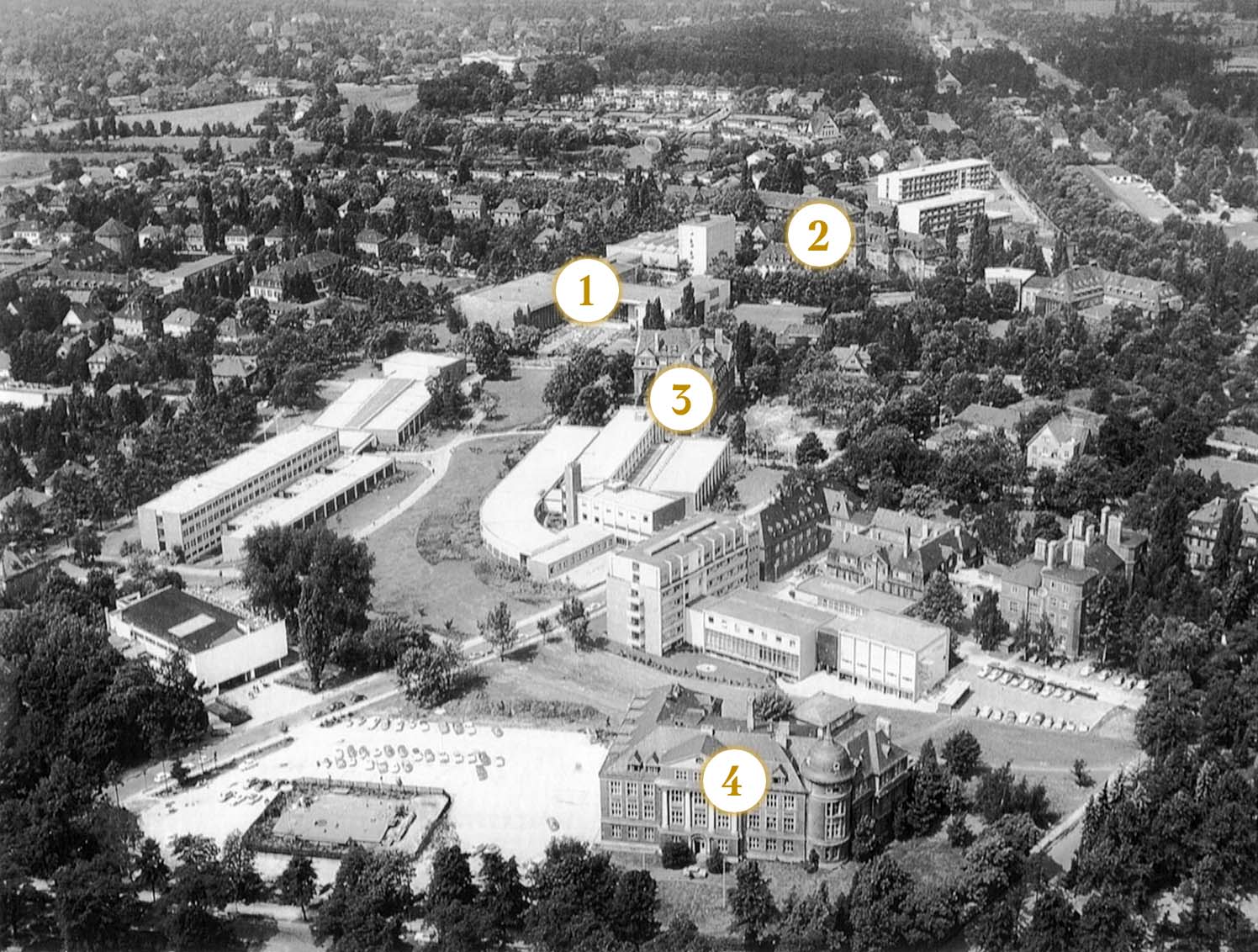

An inheritage from the Kaiser Wilhelm Society

Abandoned buildings of the Kaiser Wilhelm SocietyInstitutes, and in particular the Biology Institute’s grounds, opened up the possibility for a Dahlem South Campus as an improvised response to the developments on Unter den Linden. Initially in surrounding villas and in the course of the 1950s also in new buildings, an old research location was transformed into a university, which, however, could accommodate a maximum of 10,000 students.

- Henry Ford Building 1954

- Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics, 1927-1945

- Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biologie 1913-1945

- Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry 1911-1944, today’s „Hahn Meitner Building“

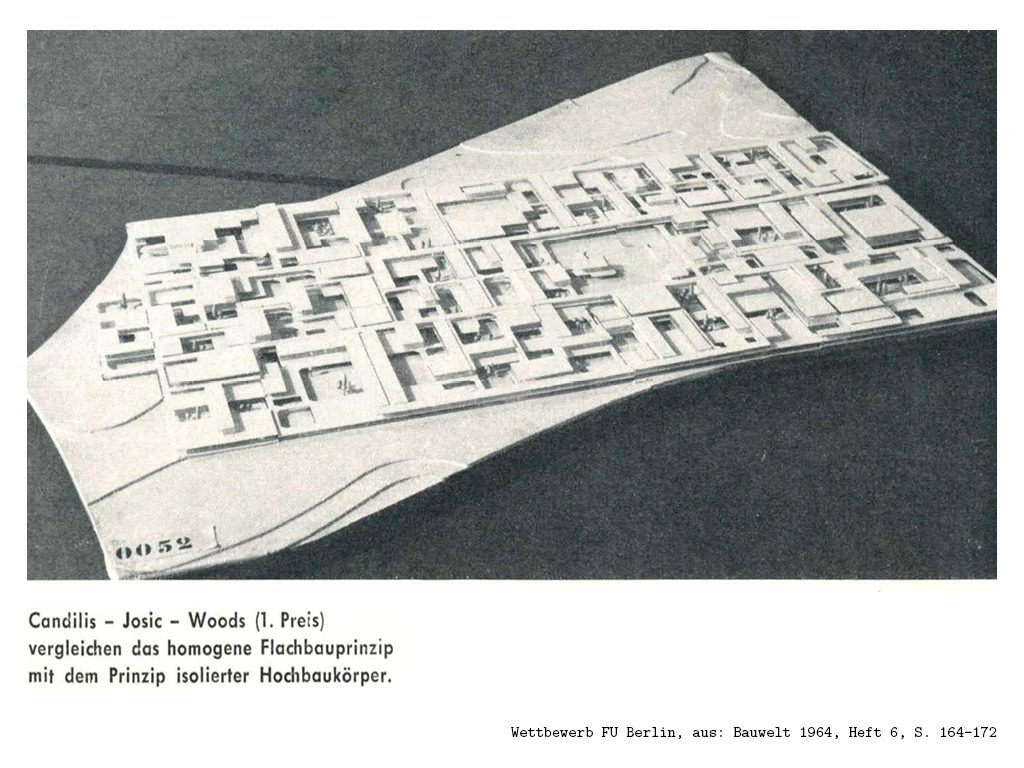

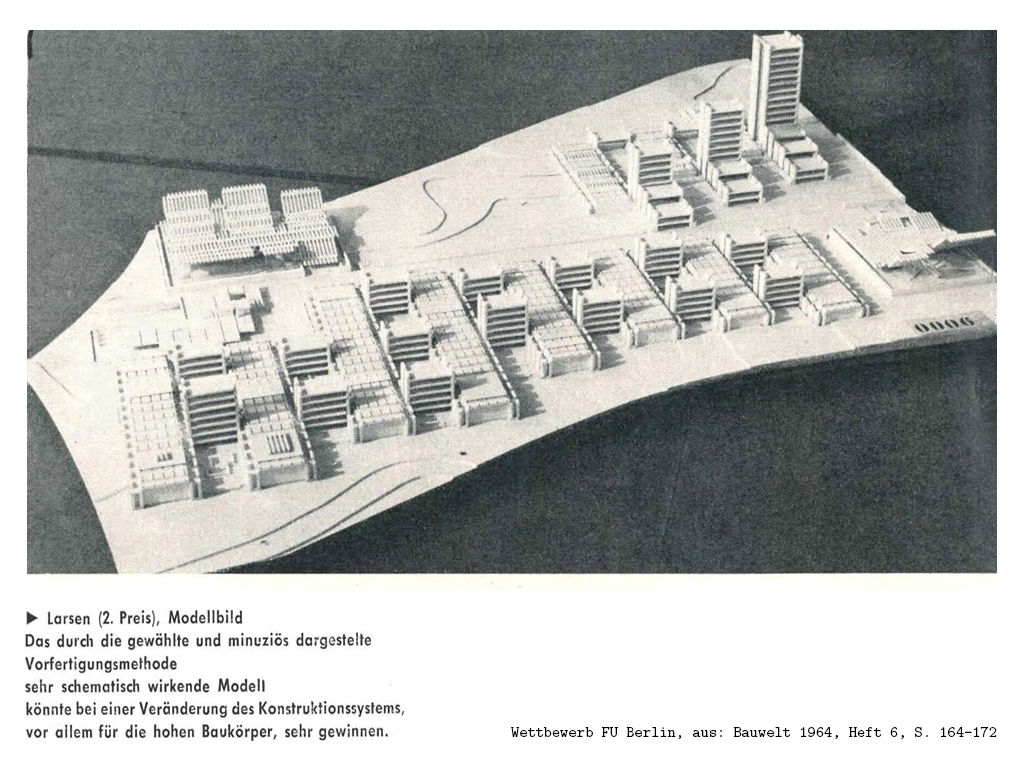

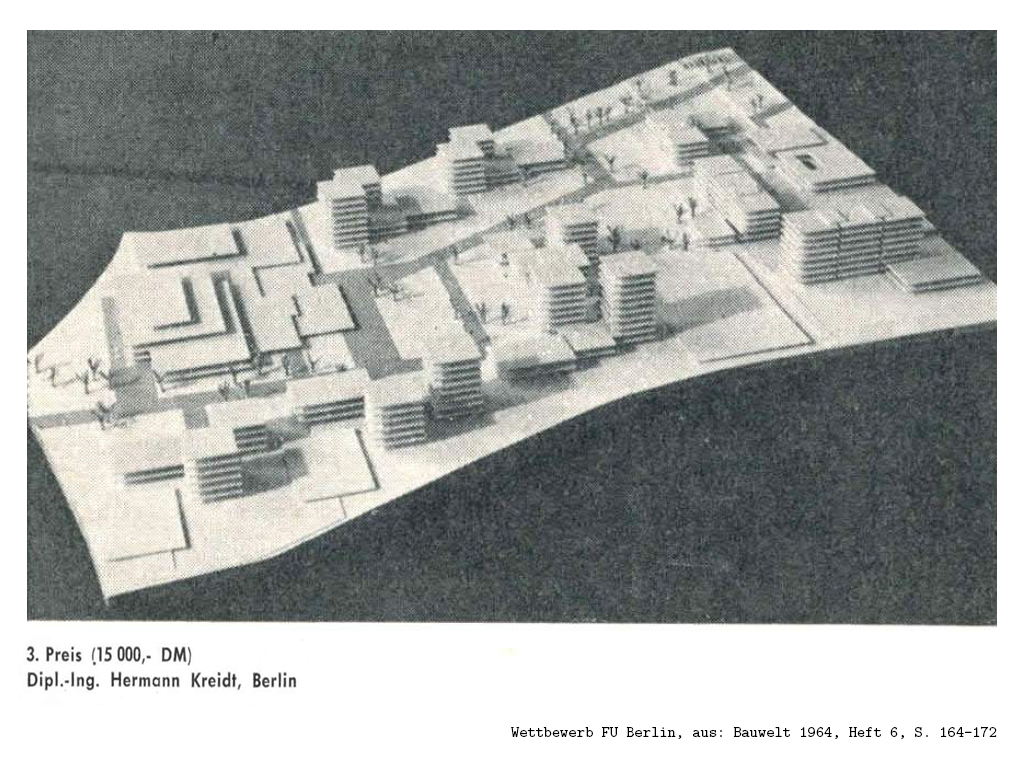

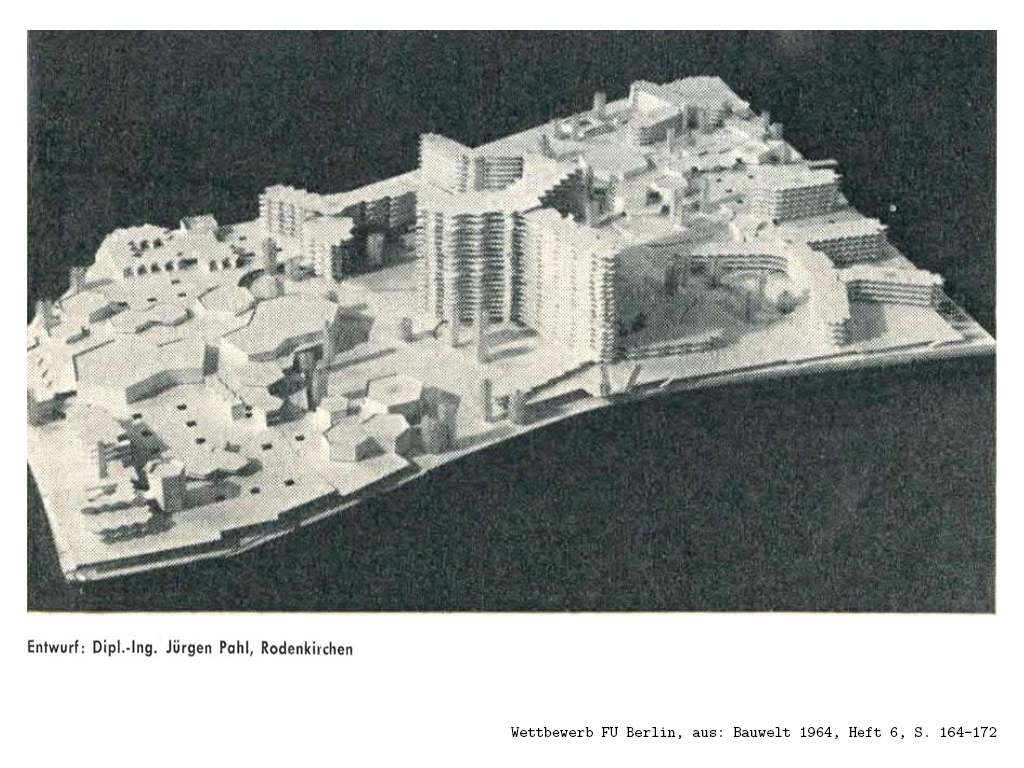

“Instrument not Monument”

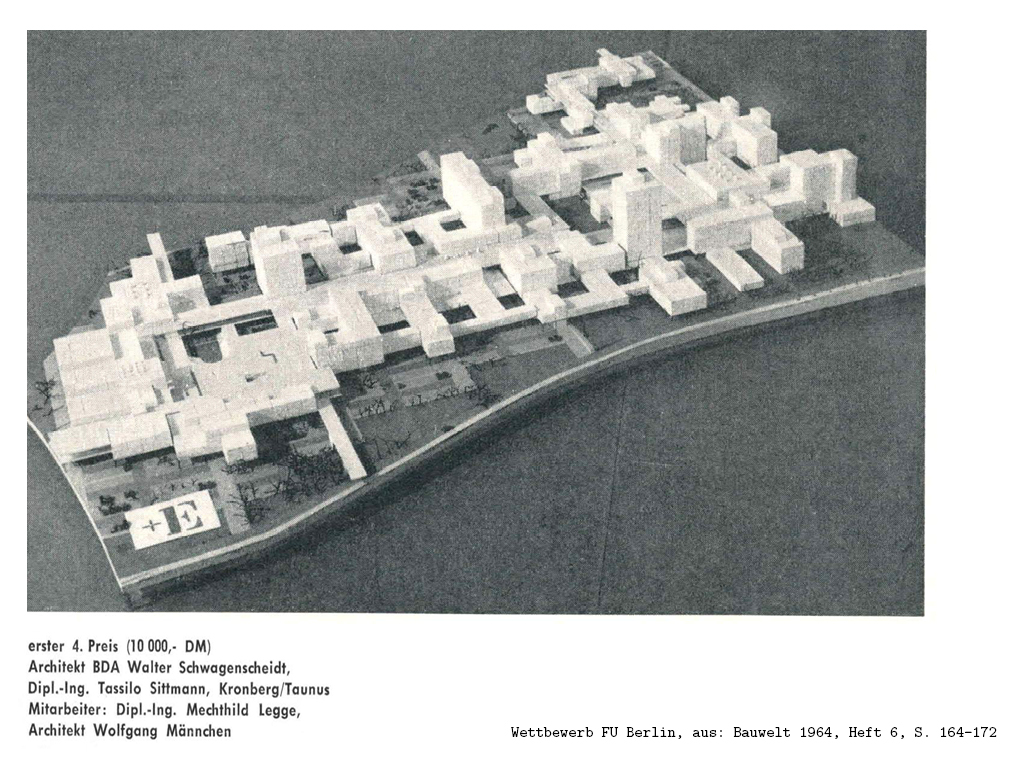

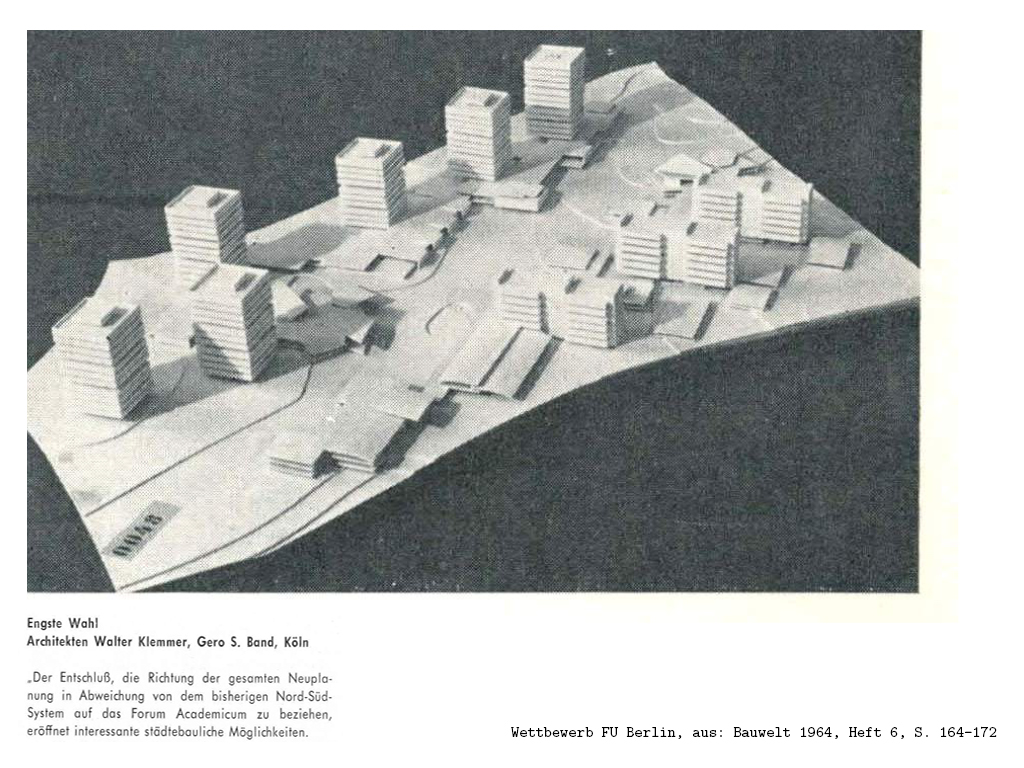

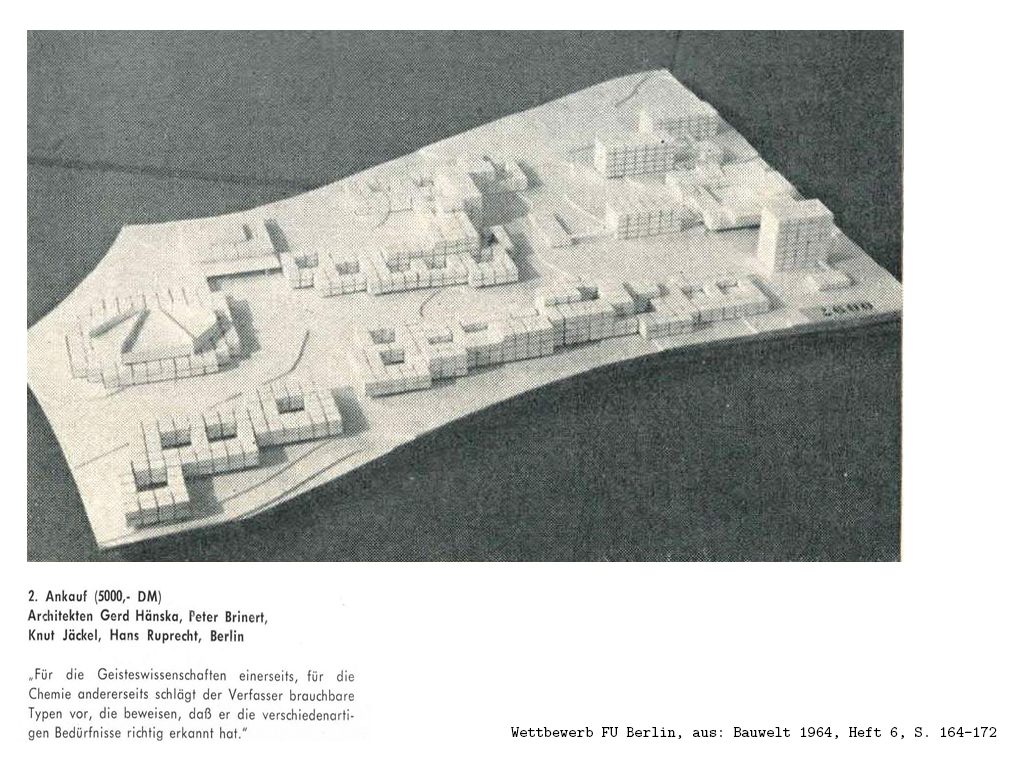

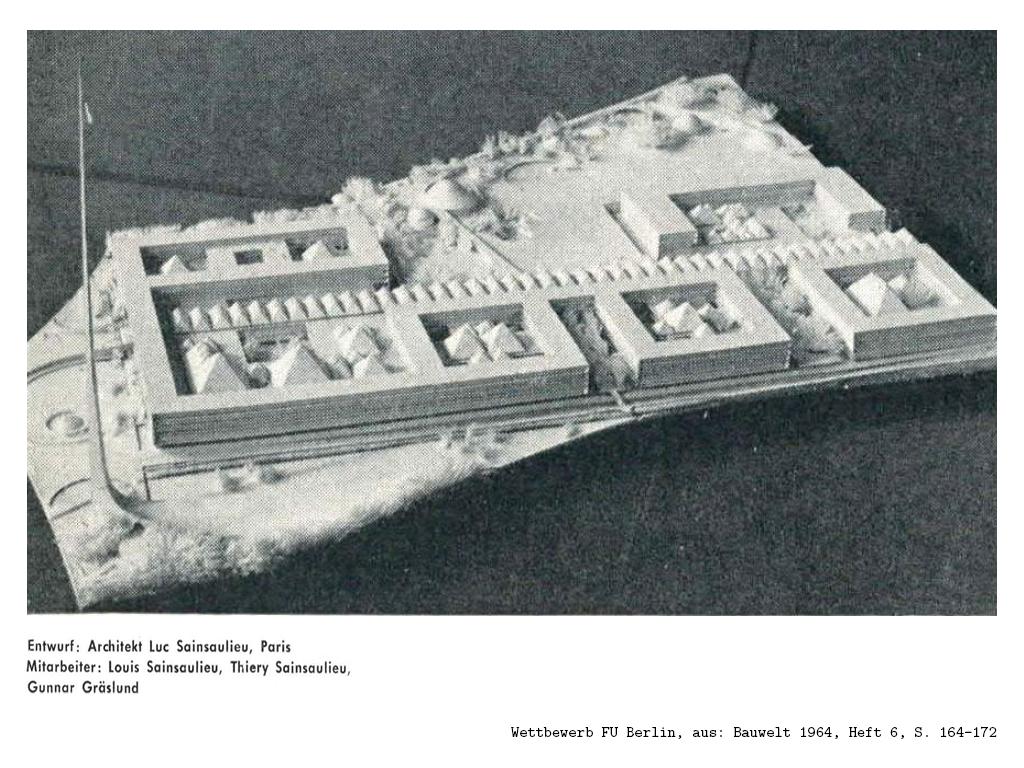

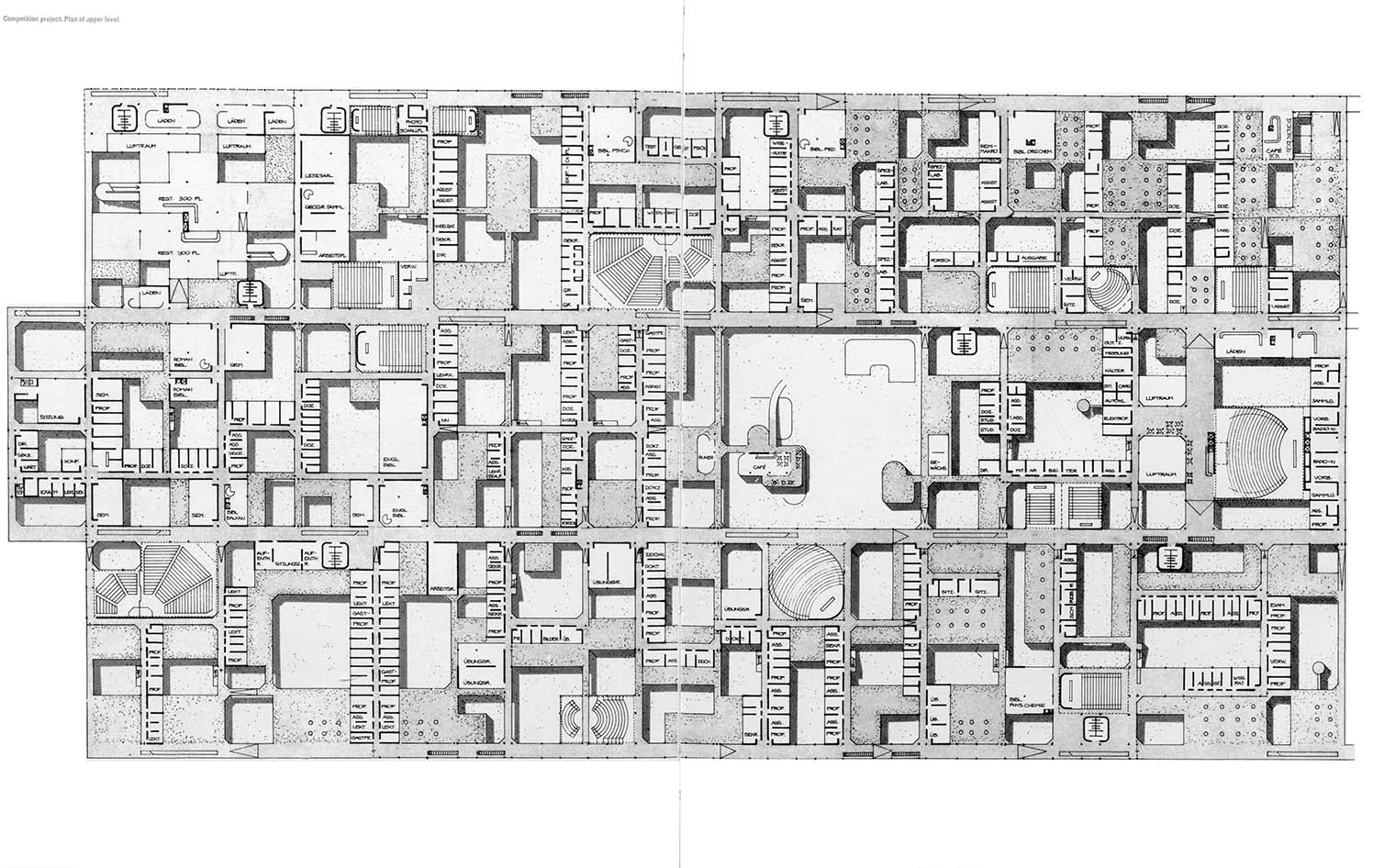

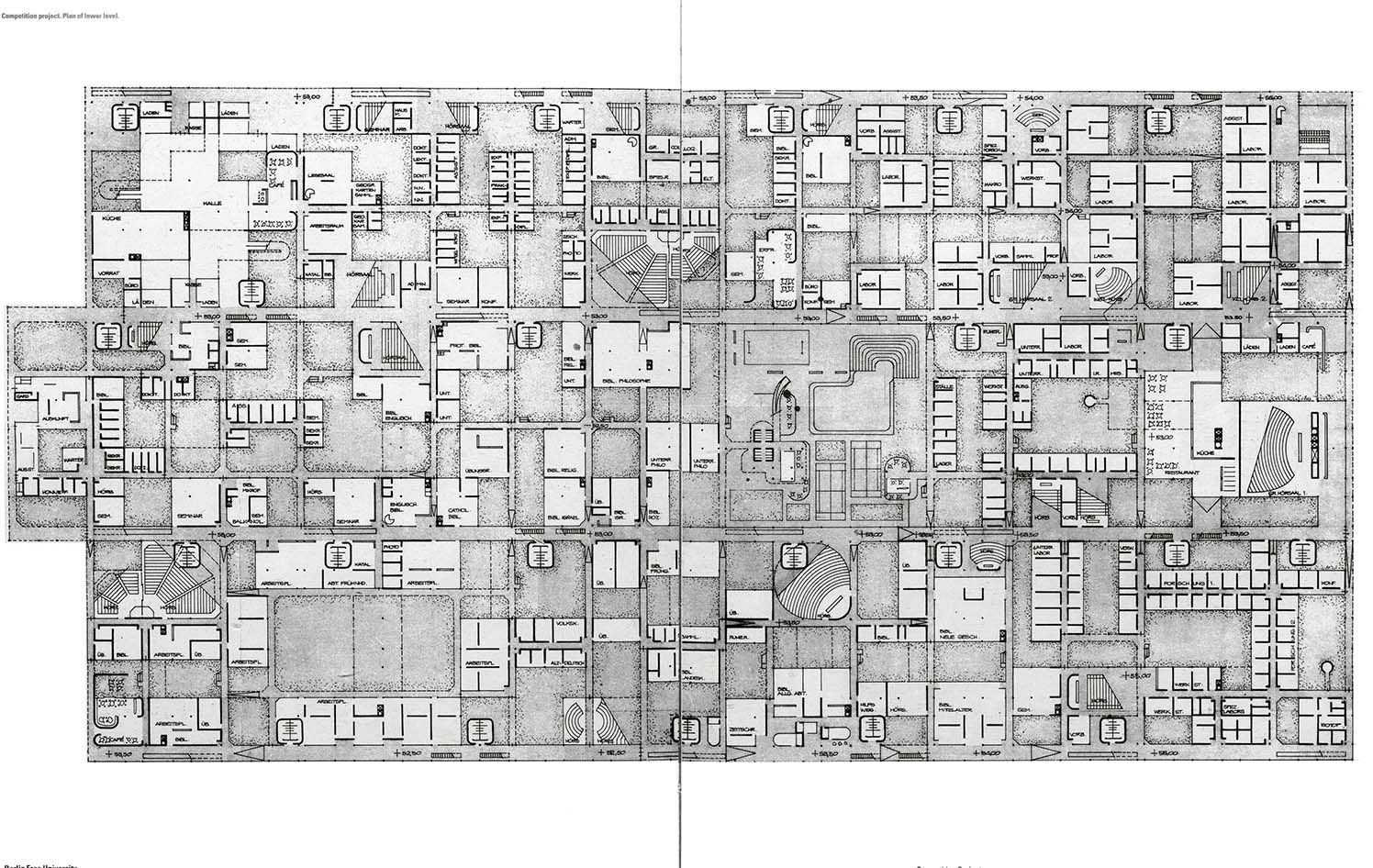

The decision taken in 1960 to expand the universities in the Federal Republic of Germany has not only created new universities in Bochum, Regensburg or Constance, but also a “megastructure” and “large grid plan” for the Free University of Berlin, which focused on seriality, modularity and prefabricated construction.

Rost- and Silberlaube

The winning design of the architect team Candilis, Josic, Woods, Schiedhelm was realised in a modified way in two construction phases: “Rostlaube” 1967-73 and “Silberlaube” 1975-79. The grid elements in the centre and south were slightly changed, in the north more compact structures for the canteen were realized.

Plan of the lower level according to the competion project proposal 1963.

6 A Heritage with a Future

6 A Heritage with a Future

The architectural diversity and outstanding architectural heritage of Berlin's universities has grown steadily over the course of more than two centuries - and continues to grow. Today, ultra-modern new venues for the sciences stand alongside historic buildings.

The oldest teaching building

Berlin’s universities preserve a rich cultural heritage with their buildings. After careful renovations, the old walls are now filled with new life. An outstanding example is the restoration of the oldest preserved teaching building in Berlin, the Tieranatomisches Theater from 1790.

A technical landmark

Since 2017, the “Pink Tube”, the circulating tank of the Experimental Station for Hydraulic Engineering and Shipbuilding at the Technical University, opened in 1974, has been shining in new splendor.

The collection will not only be preserved, but also dynamically developed and adapted to the conditions of a living knowledge society. This has been particularly successful in the construction of modern libraries.

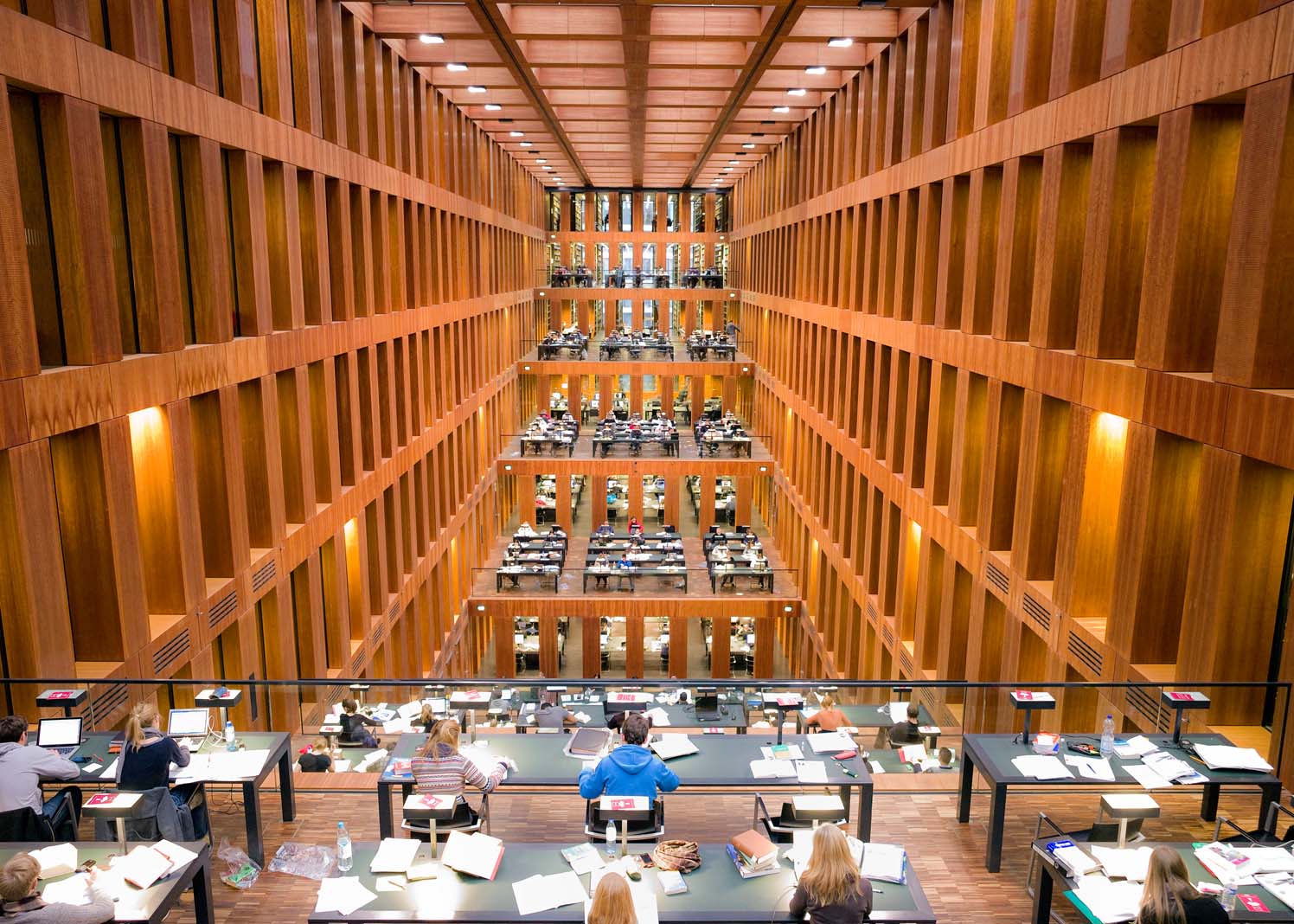

Humboldt University

The Jacob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum, the Humboldt University Library, was opened in 2009 as a spectacular knowledge store in the heart of Berlin. Max Dudler, the architect of the Grimm Centre, succinctly describes it as a place where “areas of knowledge are brought together in the Humboldt sense - and at the same time visitors are encouraged to literally cross the boundaries of these areas”.

Humboldt University

The Jacob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum, the Humboldt University Library, was opened in 2009 as a spectacular knowledge store in the heart of Berlin. Max Dudler, the architect of the Grimm Centre, succinctly describes it as a place where “areas of knowledge are brought together in the Humboldt sense - and at the same time visitors are encouraged to literally cross the boundaries of these areas”.

Technische Universität und Universität der Künste

A new university library was opened in Charlottenburg in 2004, which now simultaneously serves two universities.

Technische Universität und Universität der Künste

A new university library was opened in Charlottenburg in 2004, which now simultaneously serves two universities.

Freie Universität

In 2005 also the new Philological Library of Freie Universität was opened, which has productively broken up the structure of the Rostlaube. The Brain, as Sir Norman Foster’s building is known, continues the avant-garde claim of the location and combines exciting aesthetics with future-oriented building technology. This was inspired by the Squire Law Library in Cambridge, also designed by Normann Foster. -->

Freie Universität

In 2005 also the new Philological Library of Freie Universität was opened, which has productively broken up the structure of the Rostlaube. The Brain, as Sir Norman Foster’s building is known, continues the avant-garde claim of the location and combines exciting aesthetics with future-oriented building technology. This was inspired by the Squire Law Library in Cambridge, also designed by Normann Foster. -->

Cambridge

The Free University’s library is was inspired by the Squire Law Library in Cambridge, also designed by Norman Foster in 1996.

Building for science: New buildings are being constructed on all campuses of Berlin’s universities.

Sophisticated architecture for science has not only history in Berlin, but also a future. In this dynamic city in the heart of Europe, cultural heritage lives on. New buildings for science are being built or are in the planning stage. They too, we are sure, will enrich Europe’s cultural heritage.

Animation 1565-2019

The Project:

Architectures of Science

The Project

The exhibition documented here was realised on the occasion of the European Heritage Year 2018. It was presented at all three of Berlin’s universities – thus the discussion about scientific architecture was carried back into its historical dwellings for the sciences, with the additional intent of providing inspiration for thinking about scientific architectures of the future.

In our inquiry into the place of science in the city, we were guided by a wonderful idea from the Berlin historian of science and the university Rüdiger vom Bruch, who coined the term “Wissenschaft im Gehäuse” (science in a housing, enclosure or case). Beyond the institutional framework, this phrase also refers to the concrete locations, the lecture halls and laboratories or libraries, which facilitate the production of knowledge. Gehäuse exist in nature as mussel or snail shells, but the word can also refer to the core of an apple, in which the seeds are enclosed in the fruit. In addition, a Gehäuse can be a protective case, e.g., for a watch with its delicate movement.

This broad field of meaning is transferred to the question of what it means to build for science. The architectural form, which is to give the natural and life sciences as well as the humanities a Gehäuse and which positions the university in the city, connects the differentiated sciences with the metropolis.

By focusing on the original concepts and excluding from consideration the complicated “lives” of the individual buildings, their manifold conversions and repurposing, we were also able to integrate unbuilt projects and grandiose but failed plans and show how the architectural discourse of the European metropolises was reflected in them.

Berlin’s architectures of science combine representativeness and functionality, they tell of self-confidence and power, of hubris, destruction, and a new beginning, and they show how a rich tradition can be preserved and new works created at the same time. In this way, the architecture of science in Berlin forms a living part of Europe’s cultural heritage.

Further information

Exhibition

Concept

Gabriele Metzler, Arne Schirrmacher

Assistance

Leon Blohm, Nils Exner, Sascha Morawe, Paul Morawski, Victoria Thum, Maren Wienigk, Mona Wischhoff

Design

Konrad Angermüller, Sarah K. Becker, Katharina von Hagenow, Rosanna Wischoff

Translation

Jim Cambell, Christopher Hüttmansberger, Arne Schirrmacher

In Cooperation with Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Funded by

Die Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien, Deutsche Stiftung Denkmalschutz, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin

With the kind support of the Tieranatomisches Theater

Online Exhibition

Implementation

Arne Schirrmacher

Coordination

Laura Haßler

Design

In accordance with the legal provisions of copyright law, efforts have been made by those responsible to identify all rights holders. Should there still be any claims that have not been taken into consideration, we would be grateful for notification.

The data protection statement of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin applies.